Sometimes, the only way forward in life is to take it stitch by stitch.

Last winter, the Masorot chapter of the Pomegranate Guild of Judaic Needlework took a field trip. This convivial group of women visited the Notorious R.B.G. exhibit, honoring Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia. But they didn’t go alone.

They brought a framed needlepoint with them, designed and stitched by member Bonnie Bacich. It depicted Justice Ginsburg against a vivid blue background. Behind her glasses, her eyes were blank—like the bound eyes of Lady Justice. Around the edges, Bacich’s friend Arlene Spector added a biblical quote to the design: “She speaks with wisdom and the law of compassion is upon her tongue.” (Proverbs 31:26). When the museum posted a picture of it on social media, what drew my eye was Ginsburg’s signature lace collar, jutting up and out of the flat canvas, a separate piece of sewn-on lace, studded with small pearls.

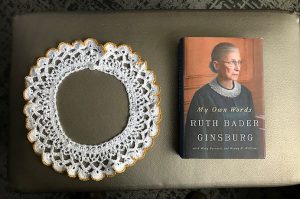

That collar tells you why Ginsburg means so much to so many Americans. Lace takes time. Whether it’s bobbin lace or needle lace or crochet openwork that resembles lace: each bit builds upon another. The stitches mirror Ginsburg’s layered pursuit of progress. Ginsburg’s jabot collection was composed through methods akin to her litigation strategies. Her incremental approach to the law was, in the end, her legacy: a wide fabric of justice, studded with silken threads.

“The more I learned about her, the more I adored her,” Bacich told me this week. “She found ways to tackle problems that nobody else thought about.” Though she’s not Jewish herself, Bacich married a Jew, and raised Jewish children and grandchildren. A self-identified “women’s libber” who was the first in her family to go to college, Bacich said the other Pomegranate Guild members were thrilled when she created RBG needlepoint kits for each woman to make. “They felt she was a role model, such a strong woman.” They expressed that admiration in thread.

Matter matters in Justice Ginsburg’s memorialization and emerging hagiography. When you see a white lace collar over a black robe, she is the first person who comes to mind. As Americans mourned her death, memorials popped up all over the country. Of all the votives offered in her memory—candles, flowers, rocks—the white jabot stands out most starkly in photographs. A collar graced the neck of the Fearless Girl in Lower Manhattan. Other young girls, made of flesh, not bronze, wore collars as they paid tribute to her on the steps of the Supreme Court. If you want to get in on the crafting, then you too can download and cut out a paper dissent collar to wear, or knit up this Dissent sweater pattern on Ravelry.

Lace and yarn and fabric are also a link to Jewish history. In Europe, the Middle East, and North America, Jews created and traded in textiles: by hand, in factories, across borders and oceans. Italian Jews, steeped in an economy rich in textiles, created elaborate synagogue furnishings. In the industrial age, the Jews of Kalisz, Poland, worked in the lace-making capital of the Russian empire.

Ginsburg’s own ancestors immigrated from Eastern Europe at a time when “shpanyer arbeit”—translated as either “spun” or “Spanish” work—was at its height in that region, adorning prayer shawls, caps, and other Jewish objects, for those who could afford it. Beyond lace, Jews did so much sewing, cloth production, and gathering of used fabric that they were sometimes called “the rag race.”

Long before her death, Justice Ginsburg’s fans used the language of craft to express their admiration for her and to bestow her with gifts. Some gifts had a Jewish theme. In 2019, Moment Magazine presented her with a special collar, created by Michigan artist Marcy Epstein. Known as the “Tzedek collar,” it incorporated the Hebrew letters tsade, dalet, and kuf, which spell the Hebrew word for justice—tzedek. A quote from the Hebrew Bible “tzedek, tzedek, tirdof”—justice, justice, you shall pursue—featured prominently on the wall of Justice Ginsburg’s chambers. Justice Ginsburg wore that collar during the October 2019 opening of the court… the last October she would sit on the bench.

RBG’s collar donated to Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv.

In the wake of her death, the Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv announced that Ginsburg had donated one of her collars to the museum last March; it will appear in the new core exhibit opening there this winter. ““She was a righteous person,” Shula Bahat, a museum representative, told NPR. “She was totally dedicated to the values of Judaism.”

Justice is indeed the Jewish value with which Ginsburg, the first woman and first Jewish American to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol, was known. Another Jewish value—less known to the general public—is called hiddur mitzvah: the enhancement of a commandment. Jews can light candles in any old candlesticks on Shabbat—but if the candlesticks are carefully engraved with a floral pattern, or they are glass jars your child has painted at school, it adds beauty and meaning to the experience.

Ginsburg enhanced justice for millions of Americans. Her brilliant legal mind got her to the Supreme Court and shaped her judgements and her famous dissents. But her collars, and the signals they delivered—dissent and approval, femininity and righteousness and pleasure—encoded the proceedings with a special kind of attention, another layer to Supreme Court ritual. Those fabric beacons shone powerfully for those of us who have experienced marginalization, had to code switch from setting to setting, or learned to express ourselves through subtle cues beyond formal language.

While it’s not a huge surprise that some of Ginsburg’s collars will rest in museums—like holy relics, the objects touched by our heroes often end up behind glass, visited by modern pilgrims—it’s also unusual for such a textile to endure for generations. Fabric and lace don’t always survive.

Yes, you can find astounding Jewish textiles in many museums. But cloth and thread are fragile. They fray, they disintegrate, they burn. When I interviewed Jewish crafters around the country, Gerry Weichman, a Pomegranate Guild member in California, told me that she began making Jewish textiles in the 1970s because so many Jewish pieces were “burned out during the Holocaust.” Putting new objects into the world is an affirmation of survival, a form of resilience, a grasping of the chaos of the universe with a needle and thread.

Threads, like our bodies, are impermanent. But Ginsburg’s collars will endure. Even when the fabric degrades, their white-on-black iconicity will linger in our minds, like the photographic negative of an ebony Victorian silhouette.