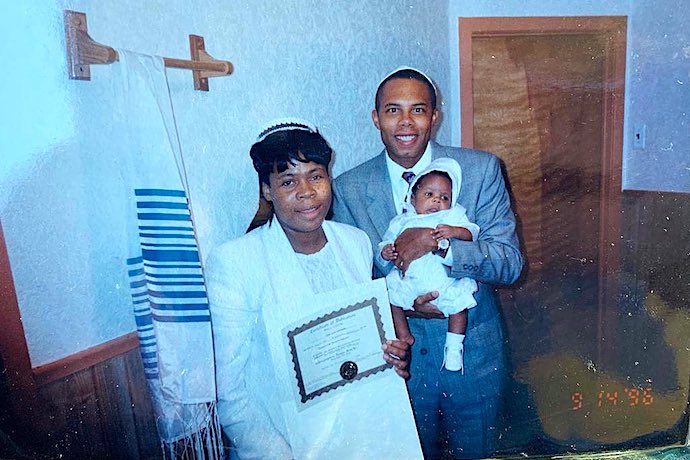

Jared Armstrong was raised Jewish in the United States and wants nothing more than to become an Israeli citizen and pursue his career as a professional basketball player for one of Israel’s leading teams. But Israeli authorities have challenged the extent of his Jewishness, potentially jeopardizing his career and also his dream of becoming Israeli. His experience raises the specter that Judaism is falling into an authenticity trap about who “looks” Jewish, “seems” Jewish, and is Jewish “enough.” Somehow this Black Jewish American basketball player doesn’t meet that increasingly subjective standard.

This isn’t only to Israel’s detriment and to that of Mr. Armstrong—but it’s also emblematic of an authenticity trap that we see within American Judaism and other religious communities. Whenever we conflate “traditional” with “authentic,” we reject the possibility that change is inherent to tradition and that authenticity can be used to exclude others.

Mourners in our communities demand that clergy bury people the “right way,” often when they’ve never before observed any traditional Jewish observance. Brides circle grooms seven times in a ritual that’s rarely understood, even as it centers ancient patriarchy. (For more on ‘Traditional Marriage’ rituals and realities, see Jay Michaelson’s viral piece, Traditional Marriage: One Man, Many Women, Some Girls, Some Slaves.) Sweltering in the heat of the summer, Hasidic Jews in Dallas dress in the anachronistic and unseasonable clothing of their brethren from the 17th Century Pale of Settlement, even though none of our ancient ancestors in the Second Temple period wore anything of the sort.

Centuries of rabbis have attempted to eliminate or alter the Kol Nidrei prayer from Erev Yom Kippur services, only to repeatedly discover that the experience of the prayer—a prayer likely linked to Conversos, Jews posing as Catholics during and after the Spanish Inquisition—is the anchor of authenticity for many Jews.

The bereavement ritual of sitting shiva has inspired its own digital platforms that delineate authentic mourning practices to enable mourners and comforters alike to know proper scripts and behaviors. Those looking for magical expressions of Judaism may find numerous ways to buy protective talismans and healing cups purported to be blessed by rabbis and imbued with kabbalistic power.

In mythologizing the look and sound of a ‘real’ Jew, and the feeling of the ‘real’ ritual, we diminish the depth and diversity of Judaism, and place Jewishness into narrow focus. Who’s more authentic, the Sefardi Floridian, the Ashkenazi Californian, or the New York Jew By Choice?

Is it more authentic to gamble with a dreidel on Chanukah (or is it Hanukkah?) despite millennia of prohibitions against gambling, or for a rising Bat Mitzvah to chant from the Torah despite the taboo of such female-identified leadership for much of Jewish history? Is a German drinking song a more authentic melody for the hymn Adon Olam than “Take Me Out to the Ballgame?”

The authenticity trap encourages myopia and ducks the inherent complexity and re-mixings found throughout Jewish history. It serves to bolster the identity of the few at the cost of belonging for so many others; and while it plays into the insecurities of modern American Judaism, it does so at the expense of seeing a Judaism that is more than a selective retrospective gaze.

When examining the retrospective focus of many Jewish institutions over a century of dramatic change in America, one must note who wins from this posture of stasis. It’s those with the most accumulated privilege—people who look and sound and just plain seem like “authentic” Jewish leaders—the straight, cisgendered white male rabbis like us.

In 2017 every single one of the top 28 earning Jewish non-profit executives were men, and in 2021 still 16 of the 17 largest Jewish federations are led by men. According to the Reform Pay Equity Initiative, women still earn just four-fifths of what their male counterparts do within Jewish institutions. Rabbis are the highest paid clergy in America. Together, those data show just how much the subjective notion of authenticity conforms to the contours of power.

Yet as the myth of the ‘sage on a stage’ continues to unravel, and the doors of some legacy institutions close, the allure of authenticity at the expense of empowerment will wane. Ultimately, a broader definition of authentic connection to Jewish tradition may enable our Diaspora to realize its potential. A return to the era of the early rabbis may be afoot, in which we all learn and teach, pray and gather, lead and reimagine. The distinction between lay leader and clergy, institution and network are already beginning to blur. Their continued confluence is our path forward.

The majesty of our tradition comes from learning and practicing, not possessing it and claiming to speak for its entirety. Contests over “authenticity” tend to trap power and belonging in the space of the few and the privileged. In reducing our reliance upon it, we may extend a sense of belonging to all who seek it.