Highlighting the protean nature of contemporary religious identity, a 2008 Pew study found that 28 percent of adults had left their childhood denominations for other groups — a “remarkable amount of movement by Americans from one religious group to another” in a lively religious marketplace.

How else could a region settled by Anglicans and Presbyterians be transformed into a Baptist and Methodist Bible Belt?

How else could the “sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners . . . sit down together at the table of brotherhood”?

Though such trends may have accelerated in recent decades, America always has been a land of religious conversions.

Rachel Held Evans author of the new book Searching for Sunday: Loving, Leaving, and Finding the Church. Photo via the author’s website, RachelHeldEvans.com

Enter evangelical darling Rachel Held Evans, author of the popular A Year of Biblical Womanhood and other memoirs, including her most recent Searching for Sunday: Loving, Leaving, and Finding the Church, which chronicles her journey from the evangelical subculture to the Episcopal Church.

Raised in the American South, Evans was “baptized by Martin Luther King, Jr. and George Wallace and Billy Graham.” In Evolving in Monkey Town (set in her hometown of Dayton, Tenn.), Evans describes her transformation from the “girl who knew all the answers” to an earnest spiritual seeker.

While technically a member of Generation X, Evans identifies “most strongly with the attitudes and ethos of the millennial generation.” Like many millennials, she is skeptical of large institutions, including the evangelical megachurches of her youth. Tired of “strobe lights and fog machines,” she rejects the gimmicks of the church marketing gurus.

Like so many of her cohort, Evans is “tired of the culture wars” and supports the civil rights of LGBT Americans. While 43 percent of white millennials in evangelical churches favor legalizing same-sex marriage, 51 percent support laws prohibiting discrimination against gays and lesbians.

Going further than many younger evangelicals, Evans actively celebrates the spiritual journeys of LGBT Christians. A strong supporter of the Gay Christian Network, Evans no longer feels at home in conservative evangelical congregations. Such discomfort has contributed to religious disaffiliation among millennials (31 percent say that negative treatment of gays and lesbians may have led them to leave a childhood faith).

In After the Baby Boomers, sociologist Robert Wuthnow describes the “spiritual tinkering” of America’s 20-somethings. Evans uses a similar metaphor, arguing that “we’re all cobblers…piecing together our faith, one shard of broken glass at a time.” Rather than reveling in brokenness, she works to transform these shards into a stained glass window.

This quest for wholeness leads her to the doors of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Cleveland, Tenn. Organizing her memoir around the sacraments of baptism, confession, holy orders, communion, confirmation, anointing the sick, and marriage, she longs to “touch, smell, taste, hear, and see God in the stuff of everyday life.”

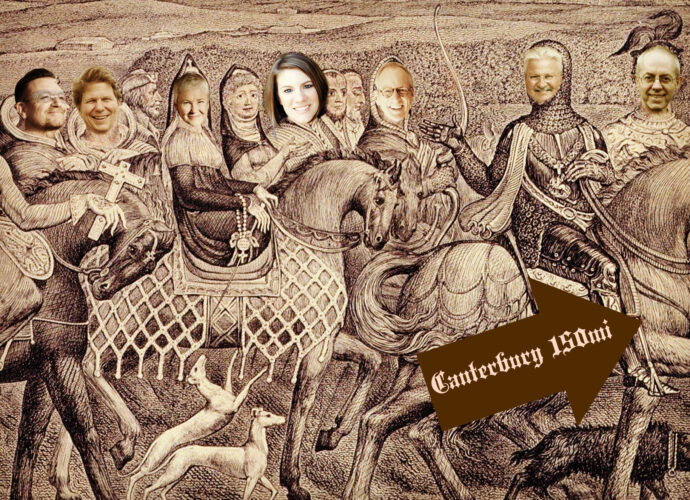

Evans is not the first evangelical to describe the allure of liturgical Christianity. Though religious switching to the Episcopal Church remains quite rare (0.7 percent of Americans have left a childhood religious group for the Anglican/Episcopal tradition), it is fairly common among evangelical writers and intellectuals. From the historian Randall Balmer and the author Ian Morgan Cron, to the poet Luci Shaw and even Bono of U2 — evangelicalism’s creative class is loaded with Anglicans.

Parts of Searching for Sunday could have been lifted from the works of Thomas Howard. While Christ the Tiger: A Postscript to Dogma (1967) chronicles Howard’s journey from Philadelphia fundamentalism to literary Christianity (under the tutelage of C.S. Lewis enthusiast Clyde S. Kilby), Evangelical is Not Enough (1984) recounts his discovery of ritual and ceremony, altar and sacrament. An Episcopalian at the time of its publication, he later entered the Roman Catholic Church.

In both content and tone, Searching for Sunday has even more in common with Robert Webber’s Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail (1985). Quoting Webber’s observation that “God works through life, through people, and through physical, tangible and material reality,” she is on a similar pilgrimage.

In both content and tone, Searching for Sunday has even more in common with Robert Webber’s Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail (1985). Quoting Webber’s observation that “God works through life, through people, and through physical, tangible and material reality,” she is on a similar pilgrimage.

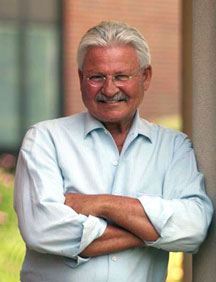

Like Evans, Webber struggled with existential questions, questions he articulated in a 1969 chapel talk at Wheaton College. Lamenting the “silence of God” in the face of human suffering, he concluded with a simple prayer:

Frustration with evangelical rationalism pushed Webber “in the direction of worship and the sacraments.” Instead of looking for God “in a system,” he turned his attention to the “mystery of God’s saving presence in Christ.”

Like Webber, Evans celebrates orthopraxy more than a system of beliefs, noting that “it was the sacraments that drew me back to church after I’d given up on it.” Despite this emphasis, she is quick to proclaim her reverence for the Apostle’s Creed, arguing that “If that’s not Christian orthodoxy, I don’t know what is.”

In the introduction to Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail, Webber affirms his “high regard for my conservative past.” Searching for Sunday is more ambivalent, balancing affection for evangelicalism with sadness about its current direction.

Is Evans still an evangelical?

It all depends on your definition. At several points in the memoir, she confesses her doubts, acknowledging, “I may not worship in an evangelical church anymore or even embrace evangelical theology.”

Though plenty of Episcopalians self-identify as evangelical (it’s not clear if Evans does), most denominational classification schemes locate the Episcopal Church within mainline Protestantism.

While she may or may not endorse the doctrinal distinctives of evangelicalism articulated by social scientist Lyman Kellstedt and his colleagues (these include support for the “truth or inerrancy of Scripture”), Searching for Sunday is saturated with biblical content, the fruits of a childhood spent in scripture memorization.

Truth she can affirm. Inerrancy, notsomuch.

Evans clearly has no problem meeting a less scientific test of religious identity. According to the historian George Marsden, an evangelical is “anyone who likes Billy Graham.” Quoting Graham on page 94 of Searching for Sunday — “It is the Holy Spirit’s job to convict, God’s job to judge, and my job to love” — she passes with flying colors.

Evans’ feelings about the evangelist’s son are far more complicated. A recent signatory of an open letter to Franklin Graham, she rejects his divisive approach to American politics.

Like an estranged member of an extended family, Evans remains invested in the evangelical subculture. As she notes in Searching for Sunday, “I can no more break up with my religious heritage than I can with my parents.”

As long as evangelicalism makes room for friendly critics, she will continue to return home.

Photo Illustration of Canterbury Tales created by Tom Gulotta with The Canterbury Pilgrims Copper engraving printed on paper from the McCormick Library of Special Collections at Northwestern University via Wiki Commons. Faces L-R: Bono, Randall Balmer, Luci Shaw, Rachel Held Evans, Ian Morgan Cron, Robert Webber, and Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby.