In state legislatures across the country, Republicans are systematically making it more difficult to vote, premised on the “Big Lie” that voter fraud was behind President Joe Biden’s election. The former president and much of his party refused to concede the 2020 election loss, with most Congressional Republicans voting against ratification of the results, leading to the January 6th insurrection.

The disagreement among Republicans seems not so much between Republicans who see Democratic victories as legitimate and those who do not, but, as Adam Serwer argues, between Republicans who think violence might be necessary to hold power and those who prefer institutional malfeasance. These developments go well beyond Norm Ornstein and Thomas Mann’s dark warning almost a decade ago that the Republican Party had become an “insurgent outlier … ideologically extreme … [and] dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition.”

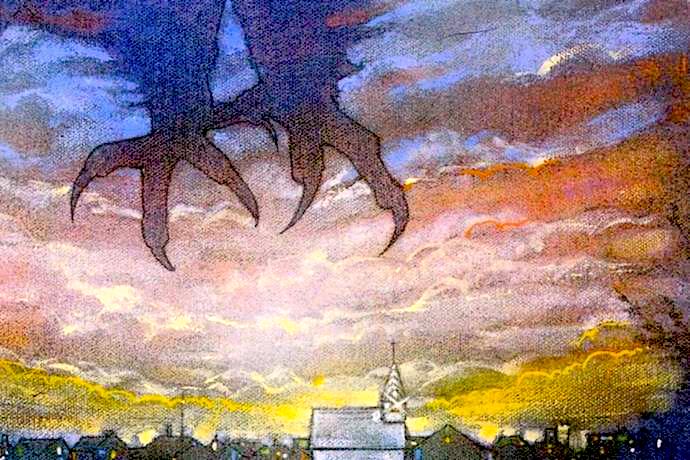

Part of the reason for the increasing Republican extremism may lie in the biblical worldview of apocalypse that animates its conservative white Christian base. Apocalypse helps explain the radical political and epistemological crisis the U.S. is now facing.

Apocalypse then

Apocalypse is the genre of two biblical books, the Hebrew Bible’s Daniel and, of course, the Christian Bible’s Revelation. Apocalypse sees the world in stark moral terms, where a hostile political state persecutes God’s chosen people. Moreover, apocalypse portrays those worldly governments as sponsored by God’s cosmic enemies. In this battle of absolute good versus absolute evil, one’s political opponents are the enemies of God—as was suggested by President Trump’s evangelical adviser Paula White in 2019 when she strode the White House grounds praying against the “demonic networks” opposed to the President and later tweeted against the “demonic schemes” and “demonic stirrings and manipulations” to which she attributed his (first) impeachment.

Televangelist Paula White, a key spiritual adviser to President Trump, brags of using her access to the White House to declare it "holy ground" that is sanctified by "the superior blood of Jesus." https://t.co/dwBFs2MCe8 pic.twitter.com/zz804kbY09

— Right Wing Watch (@RightWingWatch) September 11, 2019

As a package of theological innovations, apocalypse gave hope to the oppressed. Things were going terribly wrong—but soon God would intervene to destroy his cosmic enemies and remake the world. Apocalypse was a kind of theodicy, explaining why God allowed the suffering of His people. Besides an imminent overthrowing of an evil world, apocalypse entailed the new idea of an afterlife of reward or punishment, which helped explain the fairness of Jews or Christians being martyred while their opponents prospered.

Yet it should strike us as strange that a biblical genre aimed at giving hope to the powerless in dismal circumstances of oppression now animates the self-understanding of the most powerful single demographic in the country, conservative white evangelicals. After all, the historical circumstance of Daniel’s 164 BCE composition was Seleucid emperor Antiochus IV’s brutal persecution of Jews. Executed for circumcising their sons, forced to eat pork, and victims of state terrorism as a military parade turned into a massacre of civilians in Jerusalem, Jews sought to understand how God could permit such evil. Daniel’s answer, along with other non-biblical apocalyptic writings, was that God had powerful cosmic enemies supporting the worldly powers that persecuted the Judeans.

The forms of persecution faced by Jesus-followers in Revelation is less clear, even if the anguish is as distinct. Both Daniel and Revelation symbolically portray empire—Seleucid and Roman—as monstrous entities that had temporarily overthrown God’s proper order. Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet and such views were baked into early Christianity. Sometimes de-emphasized, apocalypse was reinvigorated by Anglo-Irish preacher John Nelson Darby in the nineteenth century. He reinterpreted apocalypse for modern times, helping to formulate the premillennial dispensationalist theology that animates evangelical Christians today.

Extreme moral dualism

Today’s white evangelicals in the U.S.—along with many conservative white Catholics and mainline Protestants—imagine themselves to be the persecuted faithful, victims of state oppression in the mold of biblical apocalypses. While this might seem ludicrous to outsiders, it aptly captures their sense of the disorder of the last half century as they’ve been compelled to share cultural and political power with other groups. As it did centuries ago, apocalypse channels the persecuted group’s fear, focusing their resentment and properly directing their anger. Apocalypse’s crucial component for U.S. politics today is this extreme moral dualism, not the imminent End Times.

Mostly opposed to desegregation and Civil Rights at the time, and with roots in pro-slavery theology, Anthea Butler reminds us, conservative white Christians have since faced the first African-American president—and then the first African- and Asian-American woman Vice President. They have seen the Supreme Court strip school-mandated Bible reading, prayer, and so-called “creation science” from public schools, even as evolution became standard fare. They have watched feminism challenge gender roles, and the Supreme Court legalize abortion and mixed-race marriage and then same-sex marriage.

They feared losing their children to a more pluralist religious landscape tolerant of decades of changes in sexuality, dress, drugs, music, and pornography. Decentered, they have lost real privileges and the ability to compel their fellow citizens’ behavior; they’ve been forced to share power. Faced with larger demographic changes, they assert what Samuel Perry and Andrew Whitehead term a white “Christian Nationalism” aimed at restoring their privileges within a Christian Nation.

The biblical apocalypses of Daniel and Revelation emphasize endurance as God’s people—Jews or Christians—await His destruction of their enemies. But antiquity’s Jews and early Christians wrote other sacred books not in the Bible, and some of them suggest that the apocalyptic imagination can tip over from passive waiting to active, even violent, resistance. In the second century BCE, a Jewish apocalypse known as the “Animal Apocalypse” envisioned an allegory of “sheep” taking up a “long sword”—probably associated with the Maccabean Revolt against Antiochus. The “Book of Jubilees” from the same century likewise imagined a role for the servants of God in a coming battle in which they “rise up and see great peace and drive out their adversaries.”

The “War Rule” found among the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran, meanwhile, foresaw in the second or first century BCE a seven-phase battle between the “Sons of Light” and the “Sons of Darkness, the army of Belial.” It was to be a struggle in which the Judean elect fought alongside Michael’s angelic forces, while Belial’s forces of darkness seem to include human armies from Israel’s traditional kin-enemies Edom, Moab, and Ammon.

Apocalypse is a contemporary genre and worldview

Vanishingly few conservative white Christians today will be familiar with these non-biblical apocalypses. But we see in them apocalypse’s potential to tip from passive waiting into active resistance. And indeed, evangelical fiction in the last forty years or so has adapted the genre of apocalypse in precisely this direction of active resistance. In Frank Peretti’s This Present Darkness, for instance, a quintessentially American town is beset by New Age spirituality, foreign religious influences and a shadowy corporation seeking control over the town’s institutions. Behind these dark forces are … demons. While most people are unaware of the demonic sponsors, the town’s evangelical Christians know, and they strengthen through prayer their angelic allies as they fight a supernatural, invisible battle. Secularists, college professors, feminists and liberals are supported by demonic networks, and Christians combat them by praying in strategic places—as did Paula White in Trump’s White House.

The influential Left Behind series by Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins, meanwhile, is a fictional retelling of the book of Revelation’s apocalypse that has sold more than 80 million copies. Mashing together Revelation with Daniel and various other biblical “prophecies,” it opens with a rapture of Bible-believing Christians. But its real story follows those left behind, who piece together what’s occurred, become born-again, and form a plan to obstruct the Antichrist—the head of the United Nations who plans to establish a one-world religion and one-world government. This includes assassinating the Antichrist, but also subterfuge and deception when opposing the Antichrist’s unwitting human servants.

In other words, evangelicals are still writing apocalypses. These influential novels embody the sense of a besieged faithful minority oppressed by a state power allied with or subservient to God’s cosmic enemies. Together with sermons, radio and television ministries, websites, Christian schooling and homeschooling, nonfiction books and magazines, the novels are part of an alternative information ecosystem that trains conservative white Christians in the apocalyptic sensibility conveyed by the book of Ephesians, which gives Peretti’s novel its title: that believers “do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (6:12).

Juiced by the conservative propaganda apparatus, contemporary evangelical apocalypse channels fear of domination, anger at their opponents, and resentment about their unjust loss of power into a program for action. Like This Present Darkness’s “prayer warriors” and Left Behind’s “Tribulation Force” opposing the Antichrist’s machinations, the Christian Right’s political apocalypse entails mobilization and engagement, not passive waiting.

Only power

Apocalypse trains its members in a structure of feeling: a proper rage at the oppression of one’s group by illegitimate state actors and their demonic sponsors—the latter of which, in any case, are invisible and presupposed. Blurring the boundary between the cosmic and the mundane, apocalypse teaches that one’s political opponents aren’t just fellow citizens with whom you have policy disagreements.

So, speaking at the Faith and Freedom conference in June and quoting the same section of Ephesians, presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis silently equated “the Left” and “the devil” [around 32:30] as the enemy facing conservative white Christians, urging them to “put on the full armor of God” and to “take a stand against the Left’s schemes.” Evangelicals are “the most likely” group to believe “that Christians are discriminated against,” and this apocalyptic expectation of persecution at the hands of their enemies leads them to politically practice an “‘inverted golden rule’—do unto others as you expect they will do to you.”

This apocalyptic imagination animated the Christian Right’s involvement in the January 6th insurrection. While it’s difficult to tell how widespread the desire for violent revanchist restoration will become, it’s clear that the Christian Right’s apocalyptic imagination includes the delegitimation of democracy we’re currently witnessing. Old democratic rules and civil norms break in apocalyptic political theology. When your political opponents are the enemies of God you don’t negotiate with them or seek bipartisan compromise. Fearful of demographic change, conservative white Christians seek to reclaim their centrality to American life and meaning in what Sarah Posner reports evangelical leader Robert Jeffress calling “a war for the soul of our nation,” and “a battle between good and evil.”

As Kristen Kobes du Mez recently wrote, evangelicals saw in Donald Trump a strongman in the model of John Wayne—not pious but willing to break rules fighting for the right side. Radically misappropriated, apocalypse shapes the Christian Right’s sense that it’s engaged in an existential struggle with the powers of darkness. There are no higher values that bind them to their human opponents; only the exercise of power. Jesus may still be coming “soon,” as he says at the end of the first century book of Revelation, but in the meantime conservative white Christians are seeking to retake the dominance they once had in a remade Christian nation.

Editor’s Note: A portion of this article’s headline, “Apocalypse Now and Then,” is also the title of Catherine Keller’s 1996 “groundbreaking work of feminist theology,” as one noted scholar put it. As per industry convention, the headline was written by the editor without the author’s input. We have tremendous respect for Keller’s work and we hope this functions as an homage of sorts. Learn more about Catherine Keller and her work here.