You have questions, big questions. Ask the Dust has answers. From the serious to the sacrilegious, no question is too high or too low!

• • • • • • dust@religiondispatches.org • • • • • •

Dear Dust,

I no longer believe any of the words of the Apostle’s Creed. I feel like a fraud around my parents, who are in their 80s and who are clinging to their faith more fervently than ever. Is it kinder to let my parents go to their graves thinking they raised at least one person who still believes (my four siblings let go of faith long ago), or is this just a weak way to justify cowardice?

NoOneKnows

Dear No One Knows,

If your parents are likely to live a very long time (God, other or no deity willing), the Dust thinks it is time to come out of the spiritual closet. Even though you are in a parent-child dynamic, you are all adults and are entitled to your own choices and beliefs. It is the only way to really form a mutually meaningful and honest relationship with them. Your unease about being dishonest or cowardly shows that they at least raised you to be a decent person, even if you are a non-believing heathen.

If your parents were on their deathbeds or extremely frail, the Dust would advise you to keep quiet and suck it up until their passing. You don’t get to unburden your soul by heaving your load onto someone else who might crumble under its weight.

Your parents had four other failed bites at this apple already so it probably won’t be a surprise that you have followed in your siblings’ footsteps, even if it is a disappointment for them. In anything though, it is not what you do but how you do it, so remember that them respecting your choice to leave religion is likely going to go better if you show that you respect theirs to stay within it.

They, in turn, will likely spend their days praying for you and may even need to mourn what they may see as a great loss. Short of them secretly dowsing you in holy water or sneaking communion wafers into your meals, you should accept these acts graciously. They and you can always cross your fingers and hope that all five of their progeny will at least make it into purgatory.

Hopefully it’s not out of the closet and into the fire for you.

The Dust

• • • • • • dust@religiondispatches.org • • • • • •

Dear Dust,

My problem is this: I think the woman I sit next to at work has joined a cult. She is a software engineer, so there’s that. (She’s definitely hard to read.) But she has started talking about mysterious weekends with The Teacher and she looks weirdly happy. Also she is coding more quickly. I have asked her, casually, what kinds of things the teacher teaches and she only smiles and tells me I’d have to come and see for myself. I am incredibly curious, but also worried that I might get sucked into something scary. Will I give away all my money? Is there really any such thing as a “cult”? Please advise.

Signed,

Not Kimmy Schmidt

Dear Not Kimmy Schmidt,

Oh cults! They start with peace, love, and happiness and then leave you eating gruel in a bunker in Montana awaiting the apocalypse—and that’s if you get one that doesn’t end in Kool-Aid.

While some sociologists study them under the broader category of New Religious Movements and endeavor to talk about these groups without the inherent stigma the word “cult” conveys, many folks who have lost loved ones, money, or their own sense of self to faith-on-the-fringes have a harder time with academic distinctions.

So, just for the purpose of your question let’s say by “cult” we mean religious or spiritual group that seems to be more about psychological (and financial) control than spiritual growth.

Telltale signs of such a project include:

1) isolation of individuals from “outsider” friends and family;

2) a new vocabulary for common concepts that makes it hard to communicate with those outside the group;

3) an extreme intolerance for questioning or dissent;

4) an infallible, messianic, charismatic leader who requires total devotion; and,

5) financial or sexual control or manipulation.

They often appeal to people who are at a transition point in their lives, going through a crisis or questioning their identity or purpose—which means we are all pretty susceptible to people offering easy, complete solutions that make us feel special and in on the secrets of the universe.

But happiness and greater productivity on their own do not a cult make. In fact the longing for a joy-filled life is at the heart of many people’s spiritual quest. So if that were the only basis of your questioning, then I’d keep an eye out for more pernicious signs like those mentioned above.

If you are interested in exploring your colleague’s magical new religion that apparently makes software engineers personable, productive, and pleasant, here are some tips:

Take a skeptical wingman/woman/person to any event that you are concerned might suck you in. Be on guard for people trying to isolate you and your wingman/woman/person from each other; that’s a common strategy to make you more vulnerable.

Remember to not make any decisions under high-pressure tactics. You’ll want to remember the phrase “I’ll think about it and get back to you” before you commit to anything. It is also helpful when trying to avoid buying a timeshare.

Write a note now reminding yourself about what a cult looks like. The Dust recommends a top ten list of “I’m probably in a cult because…

- I feel compelled to buy all new clothes, books, décor, access to life-altering knowledge with money I don’t have or shouldn’t be spending

- The things I used to enjoy and find fulfilling are all off limits and used by the group to make me feel shameful

- I can’t entertain any new ideas that don’t come from the group or group leader

- I can’t talk to my parents (I mean more than I couldn’t talk to them before)

- I’ve developed new coping mechanisms to get through things in the group that make me uncomfortable a la Kimmy Schmidt’s “You can stand anything for 10 seconds. Then you just start on a new 10 seconds.”

- I’m considering participating in a group marriage (marriage to Jon Hamm exempted, of course)

- The thousands I had saved for an actual vacation is now going to a weekend enlightenment ritual retreat in the desert/forest/mountains that couldn’t conceivably cost more than $150

- I’ve shaved my head or radically altered my appearance

- I fear punishment or retribution from the group for asking questions or not following their norms

- The messiah is standing in front of me, like he is right now at this event I’m attending in a basement/farm/isolated area in _________ (for example: Decatur).

Pin it on your wall, put it in your bag, and give your wingman/woman/person a copy too. On their own, some of the things identified above point to the natural evolution of a person over time, while some are big fat red flags. Taken together, though, these could point to a group being a cult.

More importantly, the Dust is intrigued as to what you think is lacking in your own life that makes you curious about your co-worker’s new world. Perhaps, it would be wise to engage in a little soulful (and free) introspection before you go start playing the field in search of a guru or teacher.

And remember the first rule of potentially dodgy situations: don’t drink anything pink.

The Dust

p.s. If you do go and make it out unharmed, write to us and tell us more about it. If you don’t make it out, have your wingperson drop us a line and we’ll extract you.

• • • • • • dust@religiondispatches.org • • • • • •

Dear Dust,

If a person could spare every bit of suffering, large and small, from their children, would they do it? What if it meant never knowing those children personally?

When I discovered the book Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence, David Benatar’s 2008 book of antinatalist philosophy, the title alone was an electric jolt to my consciousness. I experienced a big aha! of recognition, after which everything fell into place.

“Having children” is something adults may want and crave in order to add to their own experience, but “being born” is not a benefit to an as-yet-uncreated person. Philosophically, the non-born person isn’t harmed by a lack of existence, but they will inevitably suffer harm by being brought into existence. Thus I conclude that our urge to procreate, while merely biological and based primarily on a desire for sex, has been reinforced by religion only via the authority of personally involved Gods who have specific wishes and demands of human beings—all of which has to be taken on faith.

I had to break with a Zen teacher who told me first that antinatalism was not supported by Zen Buddhism, and, second, that people who don’t have children “don’t mature” the same as people with children. (She has a child, and I don’t.)

Is the claim true, that Buddhism (or Zen) don’t support a non-procreative philosophy? And is the antinatalist philosophy antithetical to religious beliefs in general, or not?

Most sincerely,

” Ellen Etc. “

Dear Ellen Etc,

Antinatalism and its proponent Arthur Schopenhauer basically channel the Dred Pirate Roberts of Princess Bride summing up existence as “life is pain, Highness. Anyone who says differently is selling something.”

As a philosophy it resets on the presumption that unbeing, or perhaps simply not yet being born, is a state of either non-consciousness or minimally non-suffering. And no amount of good one can experience in life could ever outweigh the exposure to the bad that inevitably will occur post-birth.

What if instead, being yet-to-be-born was the ultimate suffering and birth was the ultimate release?

Simply put the state of pre-existence is for the yet-to-be-born is unknowable. But in its unknowability, we ought not let our Zen teachers or Mommy-bloggers shame our choices about reproduction, which I suspect is really at the heart of your question. A good life can be lived with children or without. Whether it is more moral, is really founded on an arbitrarily constructed cosmic balance sheet where pain can never outweigh, let alone produce pleasure.

Ironically, only the born are arguing about the merits of being unborn, so Antinatalism itself, if it is a good, rests on the fruits of natalism.

Be fruitful and (it’s cool if you don’t) multiply,

The Dust

• • • • • • dust@religiondispatches.org • • • • • •

_______

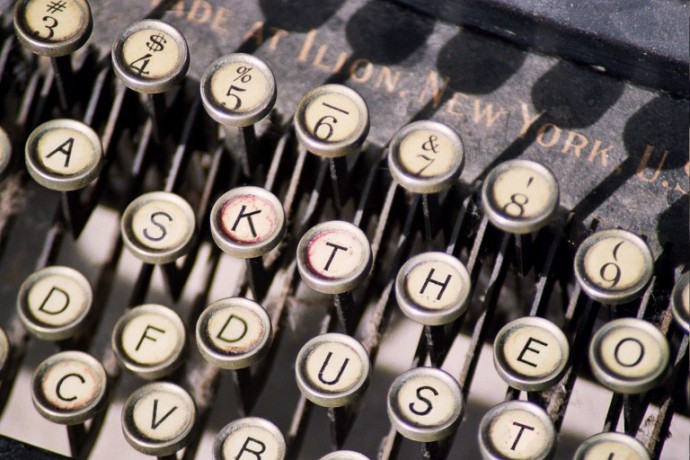

John Fante was a writer whose explorations of “God, booze, women, and the cruel majesty that is L.A.” made him a noir legend. His 1939 novel, Ask the Dust, inspired the title of this column. A pertinent excerpt: “This was the life for a man, to wander and stop and then go on, ever following the white line along the rambling coast, a time to relax at the wheel, light another cigaret, and grope stupidly for the meanings in that perplexing desert sky.”