“I was dreaming when I wrote this forgive me if it goes astray” – Prince

I started writing this before the announcement of the verdict. I want to start writing while the angst, the fear, the anxiety is still very real. I want to write while my stomach is still in knots with skepticism that a small sliver of justice may be possible. Like many I have learned not to get too optimistic about the possibility of justice being served. To be honest I have tried to protect myself from this moment. I refused to watch the death of George Floyd as it was simply too traumatic. Neither could I watch the trial, opting to follow daily news reports and social media feeds. But now the moment has arrived. Guilty or Not Guilty?

The jury returned a verdict of guilty on all three counts. Strangely enough I have not yet felt the same jubilation that I saw on television. I am relieved that [Let his name and his memory be erased] was found guilty of George Floyd’s murder, however it still does not feel quite real. There is still sentencing, and I am sure appeals to come. Finality does not feel quite final yet.

Dear reader, I also ask that you indulge me this instance of yimakh shemo (placing a curse upon the name) of the murderer. I first learned of this tradition in my observance of Purim at the mention of Haman. The practice of not saying the names of enemies can be traced back to the biblical text’s admonition in Deuteronomy 25:19 to obliterate the memory of Amalek. I find this custom incredibly healing in this moment and an unexpected intersection of my Jewish journey and my current traditional African religious one. As the logic goes, as long as one’s name is still called upon one is still among the living. The inverse is also true. We should blot the name of this murderer from our lips. The social death of not hearing this man’s name will have to do in this circumstance.

As the new coverage of the verdict and its respective meaning to society is being debated, I still cannot shake the unease that I feel with the forced martyrdom of George Floyd. News commentators and pundits are already proclaiming this as a new day of police accountability. Some are celebrating this verdict as a turning point in American history. And it’s that point that I’m most uneasy with.

I have been here before. My high school years were punctuated by the Rodney King beating, then the Simi Valley acquittal and the subsequent L.A. Riots (or, if you prefer, uprising). My early adulthood was haunted by the deaths of Sean Bell and Amadou Diallo. But there were also events that gave me hope. The eventual conviction of the murderer of Medgar Evers in 1994, and the conviction of the murderer of Cynthia Wesley, Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, and Carole Robertson (Four Little Girls) in 2002. I took relative solace that Americans in general felt the righting of historical wrongs were important and it gave me hope that change was possible. Even the level of outrage displayed toward the dragging death of James Byrd led me to believe that America could turn the corner.

But that hope came crashing down on July 13, 2013. That was the day the killer of Trayvon Martin was acquitted. Since that day, the numbness of the unreasonableness of black death has persisted. As the list of Black people dying at the hands of law enforcement, white terrorists and vigilantes has grown longer since 2013, I remain traumatized by the unreasonableness of white reason.

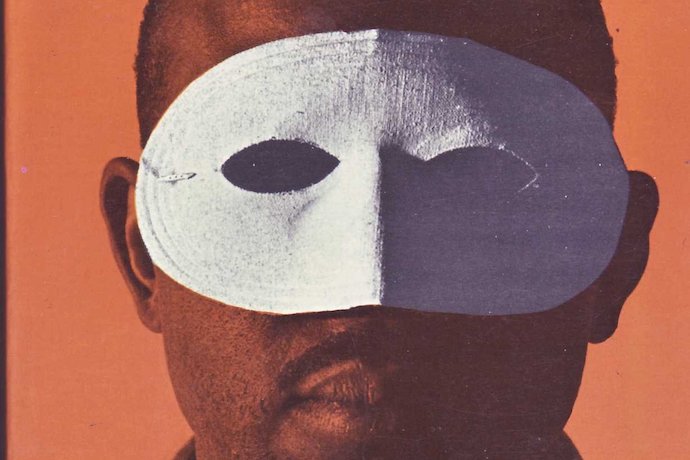

What do I mean by “white reason”? It is the presumption that Black people have the burden and duty to appear as humans worthy of basic dignity and treatment. I remember the first time I heard Africana existentialist philosopher Lewis Gordon lecture on the Martinican revolutionary Frantz Fanon. Fanon argued the faculty of human reason has been colonized and replaced with a white perception of reality. The colonized is a brute and a savage and their death (mental and physical) is for their good and for the good of civilization or, in the American parlance, to maintain law and order. This observation offers an explanation that addresses the usual outcome of these types of cases and the extraordinariness of this verdict.

Ultimately this is why I cannot fully celebrate the verdict of the trial. The trial itself took place within the geography of white reason. Like those before and after George Floyd, Black people are both the victims of and main suspects in their own deaths. From the vantage point of white reason, Black people must either be found to be so innocent that whites can relate (think of the closing argument of Jake Brigance in A Time to Kill), or the crime against the Black victim must be so appalling and horrific that it shocks the senses of white reason. The death of George Floyd falls in the latter category. America watched over and over as George Floyd begged and pleaded for his life, his mother, and simply to breathe.

However, that did not stop the defense (as to be expected) from turning Floyd into the primary suspect in his own death. The defense argued that he had a defective Black body. His death was his own fault. The ability of white reason to justify the deaths of so many unarmed Black people is built upon this presumption. And there lies the root of the problem with the American criminal justice system’s treatment of Black folks: if criminal cases’ burden of proof is ‘beyond a reasonable doubt,’ whose reason decides guilt and innocence?

Whether it’s the fantastical theories of crime based on circumstantial evidence that have led to the conviction and false imprisonment of countless Black men and women, or the uneven distribution of punishment to Black and white offenders for the same crimes, white reason perceives Black people as more guilty and less innocent. It is, as Fanon describes, “unreasonable reason.” To be clear, white reason isn’t only consigned to white people; as a colonized form of reason it’s accepted as the normative framework through which we’re encouraged to perceive reality. Hence the overall euphoria and optimism that the verdict has left many feeling about the future. While that may be justified, white reason must be jettisoned in the process.

As I write this a 15-year-old Black girl, Makiyah Bryant was fatally shot by the police she had called for protection in Columbus, Ohio. Her “crime”? Having a knife to protect herself from the abuser she called the police to protect her from. Instead of a reasonable reaction by the police, to paraphrase Fanon’s sentiments in Black Skin, White Masks, when the Black person enters reason exits and another Black child is fatally shot. White reason places the burden on Black people to continually justify their existence in life-and-death circumstances.

Try as I may, it pains me to celebrate this “victory” because it is rooted in Black death. There are two options, neither of which I am overly confident about moving forward if any progress is to occur. Either there will be substantial change to how law enforcement interacts with Black and brown people, or the system is reformed to the point that law enforcement is appropriately held accountable for these types of violations of the public trust. As counterproductive as it may seem, the true sign of progress is when a Black person’s unjustifiable death at the hands of law enforcement no longer requires nation-wide and global protest to ensure that justice is served.