It always amuses me when journalists mine the old history papers of politicians and try to use them to psychoanalyze their true positions so many years later. In the summer of 2008, someone dug up Michelle (Obama) Robinson’s Princeton Sociology thesis in an attempt to ‘reveal’ that the First Lady was a vocal critic of white power and privilege. There was little mention of the fact that her paper reflected some of the more mainstream views of academics writing on the subject—both then and now.

The same goes for the recent attention given to Elana Kagan’s undergraduate history thesis on the troubles in the Socialist Party in the early twentieth century. When Kagan wrote the paper that Time’s David Von Drehle recently sought to search for clues, she only joined leagues of other labor historians in reflecting on what the Socialist Party leader Morris Hillquit could have done differently during his attempts at strategizing alliances for reformation in the early 1910s in New York City. Labor historians far from Moscow (myself among them) are still exploring the different potential alliances that could have been formed.

The scrutinized conclusion to Kagan’s paper sounds to me like the typical, pat conclusion of an undergrad in 1981:

“The story is a sad but also a chastening one for those who, more than half a century after socialism’s decline, still wish to change America. American radicals cannot afford to become their own worst enemies. In unity lies their only hope.”

I can hardly imagine Kagan passing this assignment in 1981 without some indication of these sentiments. As leftists began to notice that the 1970s were over and some liberals were now supporting Reagan—fragmentation! was labor historians’ resounding prognosis. Were I a journalist tasked to deduce something deep and telling about this essay, it would be that Elena Kagan was the sort of student who willingly reflected the sentiments of her history professors. She had no problem fitting right in with the scholarly trends of the day.

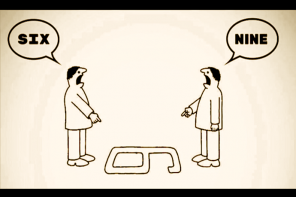

But that, to me, should bring us pause. We are now in an era when so many potential Supreme Court cases involve culture clashes between rural and urban values, but do we have anyone on the court who comes from a rural “flyover state” and who identifies with or represents these cultures? If Kagan is confirmed, five of the nine justices on the Court would be from the New York metro area. All nine will hail from either Harvard or Yale Law Schools. Why is our concept of diversity on the court so limited to gender, religion, and ethnicity?

I see a huge chasm in this country between academic opinions on class and religion and the values lived and practiced by many poor whites in the flyover states. For example, any professional American historian could tell you that the ‘red-baiting’ of public figures is a long-held refuge of conservatives, going back over 100 years, but can they stop reporting that panders to this tactic?

Any scholar of American Religion could easily refute Glenn Beck’s inflammatory statement that social justice in churches is a cover for communism or fascism. The term “social justice” has been actively promoted in mainline Protestant churches for over a century.

But, while we academics tell one story of movements for justice built by working poor people, one that prizes the term “social justice” and appreciates socialist-driven reforms, there is a contingent of the working poor who don’t see themselves in our narratives. They resent wealthy, formally educated people telling them stories that do not square with the ones their grandparents told them. Sure, their grandparents were probably bigots. But no matter what we academics think of the cultural movement in this country that entertainers like Glenn Beck have so easily tapped into, we prove their point when we offer our last seat on an all Ivy-League Court to the former dean of Harvard Law School.

Now, before you jump to recall all the legislative power that these so-called disfranchised people actually have (of Proposition 8, Arizona laws undermining Ethnic Studies, and continued attempts to undermine the teaching of evolution), be assured that I agree. The highest court exists to balance out the legislative tyranny of the majority; and the majority has definitely proven its capability of being tyrannical. However, how much of this country had the opportunity to study race, gender, and sexuality in college? How many were encouraged to explore the potential of early twentieth-century socialist politics, and have that thesis read by one of the most prominent American historians in the country? How many have had, or will have, a reasonable chance to get into Harvard Law School?

Stacking the courts with yet another elite, academic jurist may reverse some of the most recent tyrannies of the majority. But how will it manage the feelings of disfranchisement that keeps on leading to such legislative tyranny? Would a team of Ivy League juris-doctors, almost all born and raised in large urban centers, know how to represent the rural poor of middle America, even if they wanted to?