Last week there was a flurry of controversy over the public disinviting of gospel star Donnie Mclurkin to a DC celebration of in advance of the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. The mayor’s office cited numerous complaints from people who felt Mclurkin’s “ex-gay” rhetoric was not in keeping with Martin Luther King’s legacy.

While even within King’s family there’s a split on the issue of LGBT justice (Coretta Scott King is famously supportive, her daughter Bernice, famously not) an association has clearly been forged between LGBT push for equality to the civil rights movement. With the likes of Revs. Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson aligning their activism to include their lesbian, transgendered, bisexual and queer sisters and brothers, that bond is inextricably connected to the furtherance of civil rights for all humanity.

This still has not satisfied many African American clergy. Jamal-Harrison Bryant, pastor of Empowerment Temple AME Church in Baltimore famously went on CNN to denounce President Obama after his announcement in favor of same-sex marriage earlier this year. And while some black clergy did come forward in support of the president, Bryant was not alone in his opposition. Studies have shown that while black churchgoers in this country may poll liberal when it comes to certain social issues, theologically they fall on the conservative side.

Enter Donnie McClurkin.

McClurkin is a gospel artist whose music is heard any given Sunday in churches across the nation. During the summer many gather around televisions to watch him judge contestants in a singing contest on BET’s “Sunday Best.” By all accounts he is the epitome of mainstream in the gospel music arena. It would make sense to invite him to participate in a major event that features gospel music—but Donnie’s public theology proved to be too problematic for such an event as this.

Donnie McClurkin has gone on record publicly many times discussing his molestation as a child by trusted adults in his life, linking that childhood trauma to his own early homosexuality and announcing his deliverance from homosexuality as a lifestyle. While Mclurkin begain talking this way as early as 2002 it is undoubtedly his comments in 2009 that are the source of the withdrawal of his invitation to the DC event.

In 2009, at the annual Holy Convocation convention of the predominantly black and Pentecostal Church of God in Christ denomination, McClurkin took the liberty of devolving into what was meant to be a pneumatologically inspired stand against the wiles of Satan, but which looked to many like a homophobic rant supported by black conservative churchgoers.

McClurkin went so far as to refer to gays as “vampires,” and engaged in rhetoric that many in the field of pastoral care would view with alarm, knowing it would produce more guilting and damage than any good. I remember watching the livestream of the event in Memphis that year while still in seminary recalling the time-honored adage, “hurt people, hurt people.”

But McClurkin wasn’t just talking, he was doing public theology.

Public theology, I would assert, is a lost art. Long gone are the days when the artful pronouncements of Jürgen Moltmann or Soren Kierkegaard or the Niebuhr brothers, Paul Tillich, Karl Barth, Howard Thurman and Martin Luther King were regularly considered part of public conversation. Our public culture largely ignores those with roots in the academy who have been “trained,” so to speak, in doing theology.

With advances in media there are ever-increasing avenues in which the public can hear a plurality of theological voices. Long gone are the days of a handful of radio and TV preachers who dominated the airways, and the memories of Rev. Frederick “Ike” Eikerenkoetter and Billy Graham are fading with each new ministry update to YouTube and every podcast of this past week’s sermon uploaded to iTunes.

Only a handful of segments on an even smaller number of news and opinion shows on mainstream media from the historical network channels to the cable news networks actually call on the academy for trained theologians to offer their view on the social issues of the day. This is, in many ways, a slap in the face to academic theology—those same networks would never call on a law school drop out to comment on the legal ramifications of the George Zimmerman trial, or a med school student to discuss HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet and still, these same networks will call on a pastor to comment on the issue of same-sex marriage, even if he or she has no degree from an accredited college or masters program. The speaker might be a pastor of a megachurch and megaministry, but they often fail to have the same educational background as their counterparts in other fields.

The thing is, any time you invoke God in public you are doing public theology, whether it’s on the news or at the pulpit. And the public square is now exponentially larger than it ever has been in the course of human history. Granted, the Pauline epistles of the New Testament stand out as seemingly eternal documents that have been doing public theology since the genesis of the followers of the Christ, but today, nearly everyone has access to any type of theological strain that they choose. And choosing which voice to listen to can become difficult.

An example: many in religion, those who visit frequently the intersections of theology with pop culture, race, politics and economics, were able to accurately assess the discourse surrounding the sermons and subsequent comments of Jeremiah Wright, Obama’s former pastor, back in 2008. However, to the larger society, there were pitiably few people that the mainstream media called upon to help parse Wright’s brand of black liberation theology. Instead the conversation circled around political commentators rather than theologians.

Personally, I felt the ball was grievously fumbled and the history will write off Jeremiah Wright as a cult leader and those who espouse liberation theology as a non-orthodox heresy and more importantly, as a personal figure who sought to derail the presidency of the first black person for the sake of his own aggrandizement, which I feel couldn’t be farther from the truth.

In a sense, while Jeremiah Wright and Donnie McClurkin are vastly different figures, they both faced a problem with public theology. Their brand of theology is raw and isn’t packaged for a prime time news segment of five minutes or less.

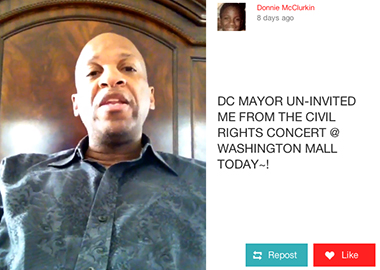

While there are segments of online communities, such as those here at Religion Dispatches, that have graciously accepted the task of doing the heavy lifting when it comes to public theological discourse, I ask the question: who will be there to help bridge the gap to what Donnie McClurkin said in his video response to the actions of the promoters disinviting him to sing? McClurkin said in a Socialcam video that “It is unfortunate that in today that a black man, a black artist is uninvited to a civil rights movement, depicting the love, the unity, the peace, the tolerance….” He goes on to say that:

“…Discrimination, bullying is still a part of this…its bullying, it’s discrimination, it’s intolerance and it is depriving someone of their civil rights when they’re told they cannot come to an event and by coming it would cause a disruption. Yet they haven’t told those 15 to 20 people who protested, 15 to 20 people compared to the thousands on top of thousands coming out to worship Jesus and to hear the gospel of music. The promoters had the greatest integrity and fought very hard for this to continue on, but the mayor office systematically and continuously shut it down…. This is unfortunate, this is intolerant, these are bully tactics simply because of stances I took; never ever demeaning, never ever derogatorily addressing any, any lifestyle. But this is a civil rights infringement situation. Imagine that in the 21st century, 2013, I, a black man asked not to attend an affair, because of politics.”

Based on those comments McClurkin doesn’t seem to see his 2009 comments of referring to gays and lesbians as “vampires” and young gay males as “broken and feminine” as speech that is considered the epitome of intolerant!

Whereas McClurkin employed a rhetoric that was the antithesis of decent pastoral care, and as speech that some could easily see as “unfortunate,” “intolerant” and “bullying,” he then turns to social media, the same platform that carried his own questionable rhetoric in 2009 to the world, to say that he is really the victim, and then oddly chooses to assert his race and gender as the reason for the discrimination.

Who is there to engage with him publicly in theological terms?

McClurkin’s seeming failure to connect the political dots with the religious is where a healthy and fair dose of public theology would be helpful.

As it stands, McClurkin is on his way to the wrong side of history.