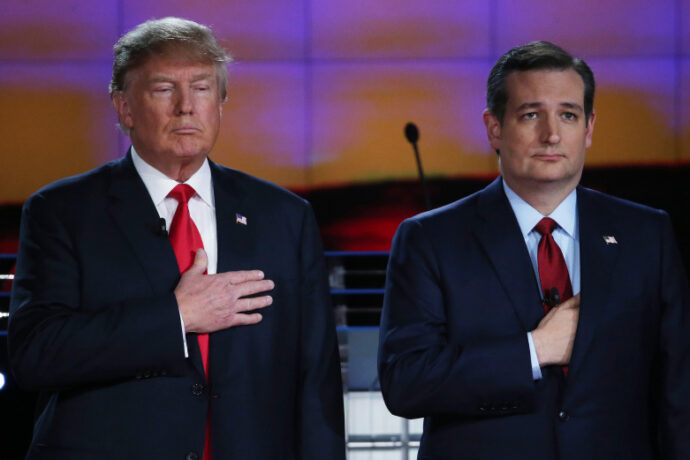

Trump, long up in the polls, stays up; Cruz is rising. What do they have in common?

Savior appeal. Of the idolatrous kind.

The two front-runners differ is some ways—among likely caucus voters in Iowa, Bloomberg News reports, Trump is considered stronger on managing the economy, illegal immigration, and the deficit while Cruz is stronger on leadership and persuasiveness to conservative evangelicals. But their common savior appeal tells us a great deal about the state of the nation.

Regardless of the final choice of candidate, that savior-hungry state is what the next president and congress face. It’s tells us where America is hurting, where it’s going, and what sort of means it’s using to get there.

Stylistically, both men court the outrageous. Trump’s provocations have dominated the headlines, but Cruz has been called a “firebrand” by Bloomberg News, while the New York Times says he uses “the most bellicose language,” second only to Trump. In Washington, Cruz is known for his showmanship, inflexibility and lack of teamwork—of which he is proud. He refused, for instance, to vote along with his party to extend the debt limit, and when this earned him the exasperation of his colleagues, he gleefully recounted their anger and “red-faced name calling” in his autobiography, A Time for Truth.

Yet bombast is but a small part of it. People grasp at saviors not only when they’re under duress but when duress itself is overwhelming. Facing nexes of complex factors, established powers, long-standing practices, and path dependencies, we suffer a crisis of efficacy. People need to feel effective—and saviors, with their programs of redemption, make us feel so.

Duress may begin as material deprivation or fear of deprivation. On Dec. 9 Pew reported that the middle class, once the largest, is the majority no longer; median middle class income has dropped 4% since 2000; four middle income jobs that accounted for 60% of employment in 1979 accounted for only 46% by 2012; and the number of persons not in the labor force is growing.

While some are getting richer, the numbers tell us, middle income earners are hobbled by shrinking purchasing power, disappearing job opportunities, and increasingly out-of-reach education.

While some are getting richer, the numbers tell us, middle income earners are hobbled by shrinking purchasing power, disappearing job opportunities, and increasingly out-of-reach education.

This is problem enough for the many who work hard and can’t figure out why they’re “losing ground,” as Pew wrote. Add to that fears of terrorism. People want relief. But if no solution presents itself, either lassitude or rage set in, along with the search for saviors who’ll deliver relief from material hardship—but who also make people feel the world is an understandable place over which they have some control and in which they have a purpose.

In 1968, Bobby Kennedy said, “even if we act to erase material poverty, there is another greater task, it is to confront the poverty of satisfaction—purpose and dignity.”

The search for grand, sweeping relief from legitimate problems is not new: one finds parallels in the appeal of fascism in Weimar Germany, crippled by war reparations, sky-rocketing inflation, and an economy in free-fall. Or in the appeal of ISIS: people suffering economic free-fall and dictatorial suppression or, in the developed world, inadequate education and prejudice. Alienation is the equal opportunity killer, reaching even those who have productive futures, especially when they see prejudice or corruption run free. ISIS promises brotherhood, goals, status, and pay.

Extreme duress, pushing people to promises of immediate, sweeping relief is a volatile mix. The results are tragic when the promised relief fails, pushing people to further anger and the search for a fix.

The most common features of the fix that doesn’t fix are acknowledgment that one is wronged and right to fight back. This is usually accurate; people know when they’re getting screwed. Yet when the causes are intricate and overwhelming, “quick-fixes” seek targets that soothe in their simplicity: targets that are identifiable, isolatable, and already a bit alien or illicit. They are easily seen as dangerous, so when we hear that they are the cause of present dangers, it “feels right.” And because they are isolatable, they are more easily tackled than complex nexes of factors we can’t pin down.

Dangerous but defeatable—we can beat ‘em, best ‘em, and win. We feel effective and the fight gives us belonging and purpose.

The “usual suspects”—racial/ethnic/religious minorities, immigrants—are just that, usual, and pernicious. The US has another: government. It’s an American belief since the 17th century that central government is corrupt and incompetent—but just competent enough to take away your rights. They’re the folks the Second Amendment protects you from.

The earliest settlers arrived already suspicious of Charles I’s centralization efforts. Religious dissenters arrived wary of persecuting states and state churches. The rough frontier settlement encouraged an anti-authoritarian do-it-yourself-ism, and voluntary associationism, as Tocqueville called it. But government is something to keep your eye on. This is a chunk of the American DNA. It was the basis for Nixon’s Southern strategy, wooing the Dixie-crats to Republican small-government-ism. It was why Reagan said government was the problem, and why so many cheered and voted for him.

And it’s the reason Bloomberg News gave—the “anti-establishment feeling”—for Iowa Republicans wanting a “government outsider who has handled complex issues and managed teams.” This was candidate preference for 39% of those polled; only 19% preferred a sitting executive like a governor. Following small-government logic, nearly 75% of Republican caucus-goers want tax cuts for all Americans (including the wealthiest); 61% want to close the IRS; and roughly 61% want to end laws enacted after the 2008 recession to regulate the finance sector and prevent another crash.

One Des Moines resident explained her politics this way: Cruz “wants to let us make choices, instead of the government being all powerful and making choices for us.”

Enter Trump and Cruz, brandishing a compendium of American quick-fixes: you’ve been wronged economically and fear terrorist attack; you’re right to push back. Overweening government and the (identifiable, isolatable, alien) immigrants and Muslims are the root of what ails us. Throw the lot out. Trump is proud of his Muslim-ban (59% of Republicans agree) and his promises to close mosques and go after the families of ISIS members. In this week’s debate, Cruz denied that he had favored a path to legal status for undocumented immigrants.

And while you’re at it, carpet bomb ISIS—another Cruz stance.

Trouble is, as a retired Israeli Army Lieutenant Colonel just reminded me, “’Zap and we’re done’ never works. Causes more problems than you had to begin with. Politicians talk like that. Professionals never do because they have to deal with the interlocking complexities of the problem and the equally complex consequences of the solution.”

Said another way, Trump and Cruz are false saviors. Quick fixes are not what saviors in the Abrahamic traditions teach. Even where there is sudden revelation—as in pietist, Keswick, and holiness forms of faith—understanding its meaning takes a lifetime of experience and study, guided by sacred texts and the accumulated wisdom of their interpreters. Words must be understood in their original context and language; undergirding principles must be prudently drawn out so that application to new circumstances accords with the fundamental ethics of the text.

The central theme of Genesis, for example, is covenant (between person and God and among persons) and the consequences its failure. Adam and Eve fail in chapter three, with consequences in exile. Humanity fails in chapter seven, with consequences in flood. The great patriarch Abraham has an uneven record (he sells his wife Sarah to other men, twice, and banishes his own son Ishmael, whom God has to step in and save) with consequences in four generations of intra-family lying, cheating, betrayal, and violence until, in chapter forty-seven, Joseph reconciles with his brothers.

Note to politicians who wave the banner of faith: “quick fixes” is not the biblical lesson. Climbing on that bandwagon is to pander after a false savior. Idolatry. And about that, among the gravest of sins, the Abrahamic traditions have much to say.