Advent is upon us as we await the coming of the world’s most famous Palestinian—Jesus of Nazareth. In this time that’s dedicated to a poor child born to an unwed mother, my conscience has forced my hand to the page.

The disdain for protest within our blessed community has troubled my spirit to the point that I cannot sleep. It is with great trepidation that I write you as your son—heavy-hearted and ashamed.

Having been baptized into the faith at 15, my formative years were shaped by the best of the black preaching tradition. In pure awe, I watched you hold congregations in the palm of your hand with rhetorical flourishes, giving a beat-down-people strength to live another day. Your words helped to re-constitute an assaulted black self—with respectability, dignity and self-determination.

I studied how you mounted the sacred desk. The way that you ‘took and walked’ a text was a dissertation in performance and homiletical studies. I took avid notes. Elegant mothers wearing peacock hats; disciplined ushers, dignified deacons in white gloves who served communion with military precision, talked back to you. In what W.E.B Du Bois named “the Frenzy,” the gathered responded: “Yes Sir,” “Go ‘head, Doc,” and my personal favorite—“You in the book.”

With the turn of a phrase, your homilies could turn despair into hope. After you had cooled anxieties—stirring souls with Holy Ghost fire—we would retire to your offices where pictures of Martin Luther King adorned the walls. I so wanted to be like you.

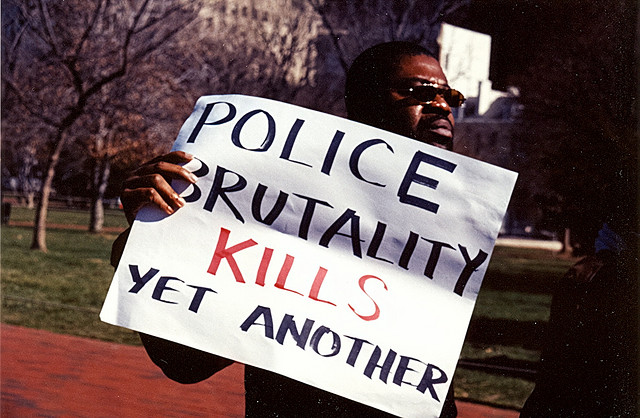

The winds of history and happenstance have carried me around the world. From the West Coast, I witnessed an unflinching youth-led resistance in the face of state terror. After spending the summer struggling to write a book about Dr. King and his relevance to this moment, God called me home. I got on a plane and flew back in time. When I arrived on Thursday, August 14, 2014, West Florissant was an occupied territory. It looked and felt like Watts, Birmingham and Palestine all at once, and I did not see you. Your absence made my presence suspicious. A clergy collar has come to signify cowardice—a scarlet letter deserving rebuke. Expletive after expletive was hurled not only at me but also at our entire class—and rightfully so. When you did show up you were often late and often wrong. Night after night, clergy told protestors to go home or else they ‘negotiated’ with police to no avail. Most then got into pulpits on Sunday morning and demonized the young folks in the streets. Sanctified folks could be seen passing out salvation tracts while teargas bellowed in the night air and youthful bodies bore the brunt of state violence.

Expletive after expletive was hurled not only at me but also at our entire class—and rightfully so. When you did show up you were often late and often wrong. Night after night, clergy told protestors to go home or else they ‘negotiated’ with police to no avail. Most then got into pulpits on Sunday morning and demonized the young folks in the streets. Sanctified folks could be seen passing out salvation tracts while teargas bellowed in the night air and youthful bodies bore the brunt of state violence.

As this year comes to a close, you have not fared much better. The terrorist attack on Mother Emmanuel AME, and the anti-Muslim venom spewed by a leading presidential candidate, revealed a simple truth— Christianity remains a barrier not a bridge.

Attacks on black churches are a tried and true tactic of the enemies of black freedom. This violent strategy is based on the belief that our churches support black resistance against state violence. Even the most hardened young black activists mourned the bloodshed in a holy space that serves to help and hold an often-broken people.

Sermons and sonnets saturated with grace offered little solace to a terrorized people. Our hearts grieved. We were compelled to forgive the terrorist who unleashed a massacre in Mother Emmanuel. The greatest sermon preached this year was not preached in a sanctuary or by a wannabe Martin Luther King. While the President sermonized about cheap grace, a daughter of the church climbed a flagpole and took down the American swastika. Like Mary and Elizabeth, Bree Newsome proclaimed that our salvation—wrapped in swaddling clothes—is here in our hands.

As an ordained clergyperson nurtured in the bosom of the black church, I am all too familiar with the way in which we tend to spiritualize the material suffering of black people. Just as religious leaders of old encouraged their parishioners to pay tithes, adhere to strict religious observations, and obey the state, so it is now.

To stand with police and politicians who demean and defame our community is not only shameful, it is heretical. You have touched and agreed with those who believe our youth are fit for the cross. At the same age when Jesus was lost in Egypt, we lost Tamir Rice. Rather than lift up their cries for justice, you have rebuked the young—telling young folks to pull up their pants.

There is something unbearable about the way you say to young folks as they are slain in the street that “they need to get saved” or “they need Jesus.” I dare say, respectfully, that your conception of Jesus and salvation is wrong.

For two millennia, one of the undisputed orthodoxies of Christianity is that God became flesh in the person of Jesus. God chose to become flesh in the body of an unwed teenage mother among an unimportant people in an unimportant part of the world under occupation. Jesus would become what his (step)father was—a carpenter, but not in our modern sense of the word. Your savior and mine—Jesus, God in the flesh—was not a skilled craftsman, but a handyman. This handyman was “crucified for us under Pontius Pilate.”

The life of those in first-century Palestine was one of degradation, filled with hunger, poverty and state oppression. Crucifixion was a grueling death reserved for insurrectionists—those who dared to defy the Roman Empire. The Roman centurions who arrested Jesus and pierced him in his side were brutal agents of the state, like the modern-day police forces.

The Roman state killed Jesus after a smear campaign and a kangaroo trial with the blessing of an apostate religious leadership who had turned the house of God into a den of robbers and thieves. The cross—the punctuation mark to our preaching—is an instrument of state violence. If salvation came to us as the child of a single mother from a place that was not known for anything good, does that not bear a striking similarity to so many of the youth we denigrate now?

Perhaps, there’s an even greater contradiction. The very people whose work you so frequently reject are actually at the center of this movement—women. From Minneapolis to Mizzou, young black women are troubling the waters. Women clergy—whom many of you will not allow to darken the steps of your pulpit—have consistently been in the streets. These sister-preachers stand in the gap between the gates of heaven and hell for our tattooed and gold-toothed youth. The Ferguson effect—forged in the streets, not the sanctuary—has set the nation on fire.

Moreover, it is a movement led and informed by queer black women, many of whom are single mothers. They embodied Jesus—while clergy send them to hell Sunday after Sunday. In kind, the holiest place in St. Louis City is not a church but rather a coffeehouse on the corner of Grand and Arsenal—where a white lesbian and her children feed the hungry, visit the sick, clothe the naked and give refuge to a movement that you closed your doors to.

And through all of this, I am ashamed on most days to call myself a preacher.

Nevertheless, I beg your forgiveness for the harshness of my words and sanctimonious tone. I am angry, frustrated and undone. To be sure, I am no angel and given to the profane. If it were not for the grace of God, there go I. Of course, if you are more concerned with profanity than with the profane conditions our people live in there’s something morally wrong with us all.

I chose to go to the streets because I could hear my neighbor cry, “I can’t breathe,” and I was saved.

I pray that you too will find your way to the altar of activism.

I call on you to open your doors to the tear-gassed, disrespected neighbors that you might be saved too. They are possessed by a fire that burns but does not consume—a holy impatience is in their eyes and feet. This same fire gave birth to the best of the Black Church, and the waters of respectability cannot put it out. For it was a queer son of the black holiness church—James Baldwin—who reminded us that God gave Moses a rainbow sign: no more water but fire now.

May this season be greeted with your willingness to come to the streets; taste and see the new things that God is doing in the Earth. As it was then, so it is now: wise men bring gifts of reverence to poor children born to nothing because they are our salvation.

Your son,

Rev. Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou