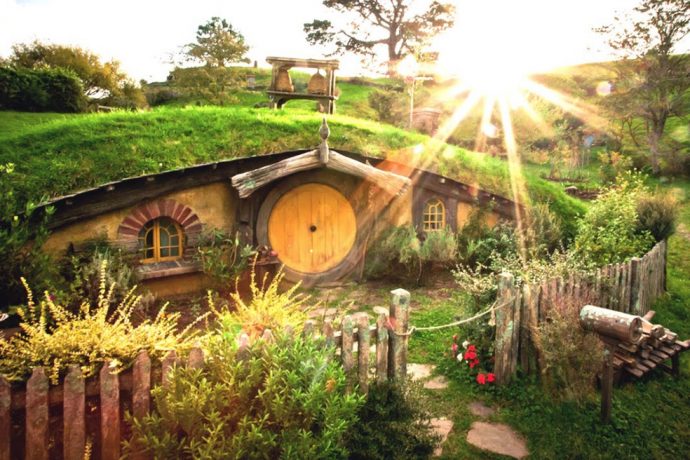

At the end of the fourth chapter of The Benedict Option, author Rod Dreher invites Christians to become hobbits. He writes:

Losing political power might just be the thing that saves the church’s soul. Ceasing to believe that the fate of the American Empire is in our hands frees us to put them to work for the Kingdom of God in our own little shire.

This remarkable pair of sentences is meant to highlight the positive spiritual effects that a shift of focus can bring about as conservative Christians lose political power. Christians can set aside their imperial ambitions and instead live like the denizens of Tolkien’s Middle-earth, in small tightly-knit communities adhering to traditional values and enjoying the ordinary pleasures of life (in right measure of course).

(“Shire,” of course, is not a word exclusive to Tolkien, but for most of Dreher’s American audience this will be the first association we make. And Dreher refers frequently to Tolkien and fellow inkling C.S. Lewis—both admirers of things medieval and Christian— throughout The Benedict Option.)

It is a charming notion: from empire to shire.

But recall that Mordor was the closest thing to an empire in Tolkien’s imaginary world. Sauron and his host of orcs spread like a disease throughout Middle-earth—battling, conquering, colonizing, enslaving, pillaging, extracting, industrializing, and polluting—in order to extend his unjust rule over every land and people.

In effect, Dreher urges conservative Christians who once identified with Mordor to reorient themselves—their identities, commitments, and communities—toward the shire.

Although they are not yet martyrs, Dreher asserts, that time is soon coming. Though they have been, most recently commanders of empire, Christians are about to be masticated by the imperial gods of sex, tech, and capital. It’s an impressive sleight of hand, especially given the recent election. But it betrays Dreher’s perspective.

Not all Christians, or for that matter Americans, have had a hand in running the American Empire. Black and brown Christians have generally not thought of themselves as responsible for the empire. Notably, African Americans and Latinos have been denied citizenship, and the rights of citizens, much less have they had political power. Too often they have merely tried to survive and resist Empire’s demands, domination, and death.

Dreher speaks as someone who has lost status and power and laments its loss—he and his people need to regroup and organize their resistance to the insurgency. But that is not a perspective that most Christians of color will share. That’s not to say that black and brown Christians are completely at ease with recent cultural and political developments. Responses vary. But for the most part, they do not speak from a place of lost cultural primacy and political power—that is reserved for the majority of white Christian conservatives.

Note also Dreher’s uncritical stance toward imperialism. He doesn’t question whether Christians should have wielded imperial power at all, nor does he discuss the long history of Western philosophical and theological reflection on empire and how to restrain the arbitrary power of ruling authorities.

Christ, after all, was a victim of the Roman Empire. Attempting to maintain imperial control over Palestine, a colonial possession, Roman authorities charged Jesus with conspiring a revolt and subjected him to torture and execution. According to scripture, the Romans did this to placate the region and maintain “law and order” (a familiar refrain).

The relationship between empire and colony is by its nature unjust and requires the continual exercise of violence. You might think Christians would be ill at ease wielding such power, but you would be mistaken. For theologians like John Howard Yoder and Stanley Hauerwas, for example, the fusion of church and state under Emperor Constantine marks the moment of the church’s decline—a kind of fall, or original sin.

Even if you don’t accept the narrative of decline, Constantine’s conversion initiated a centuries-long debate among Christians regarding political authority.

Eusebius embraced imperial power. Augustine emptied secular politics of divine significance. Popes and monarchs battled for power. We might mention the Investiture Controversy, or the papal bull Unam Sanctum. Dante wrote a treatise defending the unique ends of the religious and political authorities. Luther and Calvin also espoused strong views, as did the radical reformers. We might add John Milton to the list.

With the “discovery” of the new world came the division of lands and the extension of European authority over the natives. The Church allowed Catholic monarchs to colonize the Americas under the guise of “evangelism.” From there we might discuss the spread of the British Empire to the Americas, the founding of the colonies, and the arrival of religious dissenters. We might mention the Declaration of Independence, the American Revolution, and the U.S. Constitution and the federal disestablishment of religion.

We would be remiss if we skipped over the atrocities of slavery and the legal and theological arguments made in its favor: the denial of citizenship and humanity to African slaves. The Civil War ended slavery, with Christians aligned on both sides of the battle, reading the same Bible and praying to the same God, as Lincoln famously declared.

In response to Reconstruction, white southerners struck back with a vengeance. Segregation under Jim Crow and the accompanying deadly violence were justified by those who insisted that the mixing of races was against God’s design. The Civil Rights Movement asserted God-given dignity in the face of dehumanization.

But I haven’t done justice to the tradition. I’ve omitted much, and of course, no part of it is uncontested. That’s the point. Every text, figure, and event is subject to interpretation, debate, and reevaluation. But I simply wanted to offer a sense of the range of Christian disagreement regarding politics, empire, slavery, and race.

Dreher might argue that I’m making too much out of too little. Perhaps his use of the phrase “American Empire” was mere rhetoric. But as he reminds us, “Ideas, as we will see, have consequences.” You can’t simply throw around ideas like empire in view of the tradition (a concept favored by Dreher) of reflection on such ideas in Western civilization (another favored concept).

Rhetoric matters. Or more precisely, concepts and language matter. “The medium is the message,” to quote Dreher quoting Marshall McLuhan. If living in the truth is as important to Dreher as he claims, perhaps getting our own history matters. My argument, however, doesn’t hinge on the importance of a single line. It’s merely indicative of Dreher’s stance toward political authority when conservative Christians happen to wield it.

His view of conservative Christian political authority pervades the book and surfaces at moments when Dreher laments its loss.

Take for instance the story of Lance Kinzer, a Republican legislator in Kansas. Kinzer attempted to pass religious liberty legislation that would protect wedding vendors, wedding cake makers, and the like from anti-discrimination laws. In a deeply red state, Kinzer thought it would be a cake walk (pardon the pun). To his shock, it wasn’t. Kinzer observed that the “social conservative-Big Business coalition politics was frayed to the breaking point.” He goes on:

It was disorienting. I had conversations with people I felt I had carried a lot of water for and considered friends at a deep political level, who, in very public, very aggressive ways, were trying to undermine some fairly benign religious liberty protections.

Kinzer is served up as an example of the powerlessness and hostility conservative Christians face. But couldn’t it also serve as an example of their loss of the power to legislate at whim according to their religious and moral views? Or as an example that they now have to persuade the others over whom they wield power and whose consent is also needed if their political authority is to be legitimate?

What shocked Kinzer is that “Big Business” turned on him and that his powerful friends opposed him. (One wonders whether Dreher has considered that alignments like these are what upset people about Christian conservatism and encourage younger generations to identify as “nones.”) It’s the loss of power that he laments. Kinzer isn’t an example of anti-Christian hostility—he was attempting to provide conservative Christians with an added protection.

Denying extra protection is not the same as discrimination or hostility. Laws fail to pass all the time. Such is politics.

Examples like this, of the loss of overwhelming conservative Christian political power, pervade The Benedict Option. They are offered as proof that America is now a “post-Christian nation,” finally succumbing to the acids of modernism, liberalism, secularism, libertinism, feminism, and every other intimidating –ism. For Dreher, the problem is that the West has lost a sense of the God-given natural order that grounds a universal and eternal morality. In its place is the radically-free, autonomous individual determining right and wrong according to whim and arbitrary will. Dreher laments these metaphysical, anthropological, and moral developments. We need to be reoriented, he argues, toward the will of God.

It’s a beguiling picture. But he’s only able to tell his story by leaving out most of the history of debates within the Christian tradition itself (as I’ve outlined above), a diversity of views that Dreher conceals by his quite selective historical retrieval.

(I might also add that Dreher glosses over tensions within his own account: Christians argued for nominalism, church reform, science, and democracy; Charles Taylor supports multiculturalism; Wendell Berry, who is influenced by Romanticism, doesn’t oppose same-sex marriage.)

It’s plausible that certain understandings of secularism or liberalism are the results of faithful, theologically-orthodox views. Secularism, understood as the disestablishment of the church, has been building for centuries as a development internal to Christianity. With the Wars of Religion, Christians began refraining from biblical and theological appeals on matters of public concern since they could no longer take them for granted as common ground. None of this means necessarily, of course, that everything decried by Dreher under the labels “secularism” or “liberalism” come from the Christian tradition, but certainly many do. All of this might also mean that the certainty with which Dreher holds his natural-law views is subject to doubt.

As the debate from Constantine to Martin Luther King, Jr. demonstrates, God’s will for creation is often hard to discern. We see “through a glass darkly” and “know in part” as it were. We might think we know God’s will but are later surprised to discover that we were wrong. Christians holding something like Dreher’s metaphysical, anthropological, and moral views argued in favor of empire, slavery, and white supremacy. They thought there was a divinely-ordained order to creation and that they had infallible access to it. They were wrong.

None of this means that Dreher holds these views, but it does mean that a longer view of the tradition places his form of reasoning and his certainty into doubt. Given the fuller history I’ve very briefly sketched, we should also be on alert when Dreher conflates conservative, traditional, orthodox, and biblical Christianity and appoints himself as the true inheritor of the tradition. These are hardly the same thing.

Inventing Orthodoxy

Dreher seems to use “conservative,” “traditional,” “orthodox,” and “biblical” more or less interchangeably. On the first page of the book, he tells us that he gradually came to realize that conservative enthusiasm for the market undermined traditionalist concern for the family. Later, he makes clear that he is a conservative Christian writing for other conservative Christians. But how did his previous realization alter, if at all, his understanding of conservatism and his commitment to it? We’re never told directly how Dreher reconciled his conservative ideals with traditional values, but since he repeatedly refers to conservative Christians throughout his text, we’re led to assume that he no longer sees a conflict.

Has he adjusted his views on conservatism? Is he no longer comfortable with political conservatism but perfectly fine with theological conservatism? On page four, Dreher writes, “To avoid political confusion, I use the word “orthodox”—small “o”—to refer to theologically traditional Protestants, Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox Christians.” Besides the fact that “orthodox” and “Orthodox” are used inconsistently at various points in the text, here he clearly distinguishes the political from the theological. But what exactly is the relation between the two? Is “conservative Christian” a theological or political label? At times, it appears that theology does the work. At others, however, politics appears to be in the drivers’ seat. It would have been helpful if he had clarified what he meant.

Note also Dreher’s definition of orthodoxy. Orthodox, as its Greek etymology suggests, has to do with right thinking. Historically, this has been a doctrinal matter. Which theological views do Protestants, Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox Christians affirm together? Anyone with the slightest bit of theological training would know that these traditions differ greatly (undermining the claim that the Reformation shattered religious unity).

As best I can tell something like the Nicene Creed—for which we can thank Emperor Constantine—expresses the theological commitments they have in common. Dreher clearly means something more by “theologically traditional” than the commitments of the Nicene Creed. He wants a metaphysical view of creation that grounds a universal and unchanging morality. If that’s the case, he’s going beyond what the various Christian traditions have jointly affirmed as orthodoxy.

It’d be fair to call such a position traditional in the sense that some members of the Christian tradition have held it, but unfair to call it the orthodox view since Christians have differed on such matters.

“Tradition” is also a fraught term. Is it an unchanging canon of authoritative texts and practices? Or is it an ongoing argument about the goods that constitute the tradition itself? The former would be what the church historian Jaroslav Pelikan called traditionalism, which he characterized as the dead faith of the living. The latter would be closer to Pelikan’s notion of tradition as the living faith of the dead.

The two notions of tradition differ significantly. Dreher appears to favor the canon-like version. It’s not beside the point that Alasdair MacIntyre, one of the inspirations behind The Benedict Option and whom Dreher credits for the title, has himself been caught vacillating between the two notions of tradition. Identifying which notion is operative at any given moment gives us a better grasp of the weaknesses of the argument.

As Jeffrey Stout argues in Democracy and Tradition,

Yet once the ambiguity of the term “tradition” is made plain, it becomes obvious that the debate over the new traditionalism is best construed not as a debate between traditional and modern varieties of ethical discourse, but rather as a debate involving at least two traditions or strands of modern ethical discourse: a tradition dedicated to a very narrow conception of how traditions ought ideally to operate and a tradition dedicated to the project of loosening up that conception democratically and dialogically.

This applies equally to Dreher. He may be more modern than he acknowledges.

What about the phrase “biblical Christianity”? It’s a mistake to refer to biblical Christianity in the singular as if it were one thing. To do so overlooks the fact of two thousand years of Christian disagreement over the meaning of biblical texts. For instance, does the bible speak with one mind about Dreher’s favored institution, the family? Doesn’t Jesus in Matthew 12 appear to undermine the importance of the biological family in favor of the spiritual one?

This is just one example of where biblical Christianity might not align as clearly with the conservative, traditional, or orthodox variants as Dreher would have it. On this point, what’s also striking about The Benedict Option is its dearth of engagement with scripture beyond a few verses that serve as proof-texts. Despite appeals to biblical Christianity, the Bible itself an afterthought to Dreher’s larger project.

In the end, Dreher distorts the Christian theological tradition by telling a one-sided narrative that fits a narrow political agenda. By brushing aside the diversity of faithful Christian thought and doing away with important distinctions, he’s able to paint his views, and his views alone, as orthodox.

But history is messier, tradition more complicated, orthodoxy more capacious, scripture more foreign.

Our theological and political tradition is more accurately characterized as one of argument, discussion, and disagreement. This tradition isn’t in competition with God’s will—no one knows with absolute certainty God’s will at any given moment. Christian theology at its best has been about discerning God’s will for the times, to attempt to answer Christ’s question “Who do you say I am?” anew for every generation.

Dreher is uncomfortable with this. He’s certain of the answers. Everyone else just needs to get on board. Those who disagree doom themselves to oblivion.

But there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in Dreher’s philosophy. There are theological and political options in between the two extremes of theistic natural law and secular relativism, as if natural lawyers and relativists agreed among themselves.

Unlike those at the extremes, who know the answer before the question is asked, those of us occupying the middle ground have to do the hard work of discernment until kingdom come.

It was as true for Paul, Aquinas, and Martin Luther King as it is for us today. Though we might agree with Dreher’s call to reemphasize catechesis and formation within churches, an obvious if neglected goal, we have reason to doubt his historical narrative, social analysis, and moral theory.