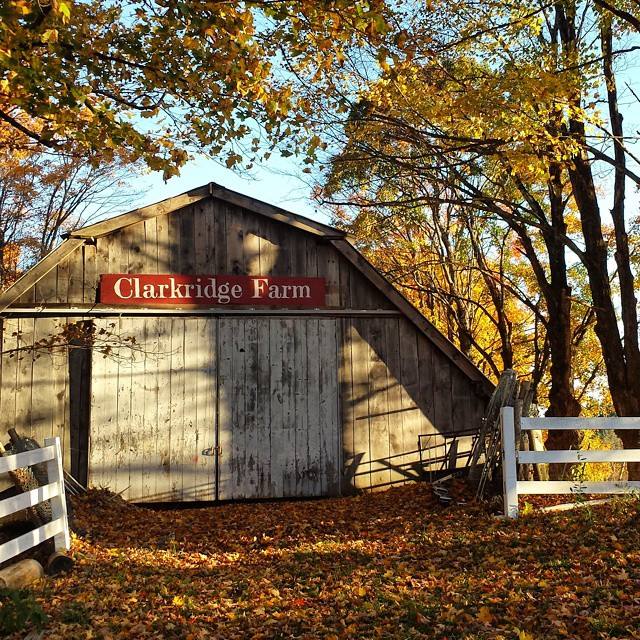

Last November, I returned to my family’s farm in New Hampshire to celebrate Thanksgiving and help build a “sugar shack” with my brother.

The “shack” was to be a small wooden structure that would house the wood-fired evaporator we use to turn sap into maple syrup in the spring.

The project took longer than anticipated due in part to our choice to use 150-year-old salvaged beams from an old shed torn down several years before on our property. The days’ frustrations culminated for me when we ran out of saw blades that could easily cut through solid steel Rebar but somehow lost their bite on the old beams.

After a long string of expletives that followed yet another broken saw blade, I caught my breath and took a moment to see the farm around me.I was standing on property that had been in my family for more than 250 years. I was using wood from a building that had stood for over a century, dismantled, and now was being resurrected as shelter for our small syrup operation.

The fields had been grazed by my grandfather’s herd of Jersey and Guernsey cows, and then my uncle’s herd of Herefords. In a few short months, we would be collecting sap from a stand of trees that had, some of them, been around since our long dirt driveway was the main thoroughfare to Boston.

Two weeks after the sugar shack was complete and my mother had begun making broth out of the Thanksgiving turkey bones, I returned to Washington, D.C., and gave notice at Sojourners, the Christian social justice organization where I’d worked for seven years.

Two months later, I began the actual journey back home.

Forsaking city life for a return to “the land” is hardly a new story. Around the time the sugar shack’s tough beams first had been roughly hewn, Henry David Thoreau penned these words:

Thoreau spent two years, two months and two days on Walden Pond. His return to the land, and the desires that brought him to it, he argued, were nothing new, “for the improvements of ages have had but little influence on the essential laws of man’s existence.”

Ralph Borsodi, a lesser known if formidable figure in the American story of returning to the land, was born a little more than 20 years after Thoreau published his Walden. He has been credited by his acolytes for inspiring hundreds of thousands of people to embrace the “simple life” during the Great Depression and the years that followed.

Originally published in 1933, Borsodi’s Flight from the City: An Experiment in Creative Living on the Land remains in print today as a practical guide for self-sufficiency, even in the 21st century.

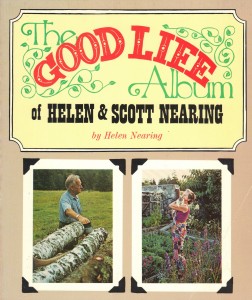

In 1954, Scott Nearing and his wife, Helen, published The Good Life: How to Live Simply and Sanely in a Troubled World, after Scott left (or was forced out of) academia, relocated to the hills of Vermont, and eventually settled by the coast of Maine. Through their continued writing about the “good life,” by the 1970s the Nearing’s farm had become something of a mecca and educational center for young people interested in going “back to the land.” The couple hosted Sunday evening concerts, intellectual discussions, and provided practical tips about how to build your own stone house or improve your compost pile.

In 1954, Scott Nearing and his wife, Helen, published The Good Life: How to Live Simply and Sanely in a Troubled World, after Scott left (or was forced out of) academia, relocated to the hills of Vermont, and eventually settled by the coast of Maine. Through their continued writing about the “good life,” by the 1970s the Nearing’s farm had become something of a mecca and educational center for young people interested in going “back to the land.” The couple hosted Sunday evening concerts, intellectual discussions, and provided practical tips about how to build your own stone house or improve your compost pile.

Rapid social change and economic instability often serve as capstones for a cultural yearning for simpler, more authentic living.

Thoreau complained about college debt and that his previous work as school teacher could barely keep him afloat.

The implicit and explicit promises of the Roaring ’20s left an entire nation questioning the forces of globalization, industrialization, and urbanization. Families flocked to Borsodi wanting to learn how to live sustainable lives of self-sufficiency, not just escape to the woods for an extended hermitage or journey of self-discovery, as Thoreau had.

Watching as inflation siphoned away nest eggs tucked into savings accounts in the 1970s led to a large-scale interest in investing in the tangible asset of land. The Nearings taught their acolytes how to invest in soil and get one acre to produce enough food to feed 30 families.

Broad economic and social forces offer a partial explanation for why innovators and experimenters such as Thoreau, Borsodi, and the Nearings gained broad audiences when they did. But the ideological commitments of the people who strove to follow in their footstepswere as diverse as the gardens they cultivated.

Thoreau, still writing in a predominantly agrarian milieu, saw the greatest expression of these values in the day laborer who lived simply and could earn all the money he needed for a year in six weeks of hard work. And yet Thoreau believed owning a farm was a limitation of the freedom he valued, saying, “it makes but little difference whether you are committed to a farm or the county jail.”

A metal bucket (one of dozens) hangs on a sugar maple at the King family farm in New Hampshire. Photo courtesy of the author.

Borsodi became a hero to the libertarian-minded with his focus on self-sufficiency and distrust in large-scale governmental and economic institutions. He was in the midst of pioneering a local currency system in Exeter, N.H., when his health declined and he died before finishing his project.

The Nearings were vegetarians, pacifists, socialists, and vocal critics of organized religion. Scott Nearing’s list of published papers includes titles such as “Why I Believe in Socialism,” “The Rise and Decline of Christian Civilization,” and “Oil and the Germs of War.”

Thoreau famously contended that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” To his mind, many farmers fell into this category. Farming, like any other form of work, could deaden one’s soul.

Yes, the Immokalee agricultural workers who pick our tomatoes use their hands every day, work outside, get regular exercise, are free from the restraints of a cubicle, and even live in “tiny home” communities (formerly known as “trailer parks”). It may sound idyllic to the young, well-educated, and the restless masses of yesterday and today. But not many of us are seek employment alongside migrant laborers because of the near constant physical pain and discomfort, regular exposure to toxic chemicals, unsafe working conditions, and economic exploitation that almost certainly ensures that independence remains a dream.

Working the land not necessarily the solution to breaking free from a life of “quiet desperation.”

Through the slow-saving power of making my own lunches, living with multiple housemates, and gradually stashing away frequent flyer miles, I am now able to patch together an agricultural self-education program that has involved trips to the deserts of New Mexico to hang out with farming monks, Portland(ia) to learn “Old World”-style butchery techniques, and have just departed the old sod of New Hampshire again, this time for farming stints in the hills of Turkey and along coastline of the Adriatic.

My story bears little resemblance to struggle of the Immokalee workers or the army of poorly-paid farm hands who are the bulwark of our current agricultural system. It is even more privileged than that of many of my peers, as I will be returning to family land with significant existing infrastructure and a debt-free tractor.

But even given such advantages, my personal “return to the land” is done with full knowledge that the hours will be long, the work hard, daily frustrations inevitable, and the financial benefit meager enough that income from outside the farm will be necessary for a substantial period of time, if not forever.

The average farmer’s income in the United States today is negative with nearly half of all farmers reporting to the Internal Revenue Service that they earn their primary living from means other than farming. In addition to such sobering realities, we have a saturated marketplace in the sense that we are producing more food, more efficiently (at least by current market measures) than ever before in human history.

Why step out of a job I liked and was pretty good at to jump into an uncertain field where, in spite my being raised on a farm, I will undoubtedly feel like a bumbling novice for the next decade?

Why jump into a world where, even if I experience the pinnacle of success, I likely ever will replace just a portion of my previous income? Why choose a path where it will be much more challenging to find a girlfriend—let alone a wife—living away from the conveniences of a major urban center and with the less-than-charming (if totally organic) persistent perfume of manure?

My reasons are myriad.

I could write about my environmental concerns, including keeping toxic chemicals out of our water sources, soil erosion, and agricultural and land use related carbon emissions, and it would be true.

I could write about my public health concerns, the obesity epidemic, and high rates of diabetes, and that would be true.

I could write my hope that changes in farm policy and market innovations could ensure that quality food access is not the privilege of the wealthy. That ex-offenders could emerge from prison to transform urban neighborhoods through working in and managing community gardens, that millions of jobs could be created for those too often edged out of the economy by “agripreneurship,” or that local economies will be more diverse and stable if they supply a greater percentage of their own food.

All of these reasons are true, in their own way. But they’re not the real reason why I headed back to the farm.

To quote the great prophet of this contemporary agrarian movement, Wendell Berry, “it all turns on affection.”

In a 2012 lecture, Berry cites his old teacher, Wallace Stegner, in describing what he calls “boomers” and “stickers.” Boomers are people motivated by greed and power. Stickers, by contrast, are motivated “by affection” and “such love for a place and its life that they want to preserve it and remain in it.”

The root of affection, Berry argues, is imagination. Far from being ethereal and disconnected, imagination thrives “on contact or tangible experience.” It is when we imagine the well-being and future of the place where we are the things that share that place with us that we enter into a state of sympathy. Sympathy ignites a personal concern for the well-being of that place and the things with which you share it that produces affection.

Affection, “is nothing if not personal.” It’s never abstract, but always rooted in concrete manifestation.

I may have an interest in farming, but I possess a deep, yearning affection for Clarkridge Farm on New Hampshire’s Route 13 in the town of Goffstown, not far from the border of Dunbarton.

What changed for me that day while cursing and cutting rebar began in seeing the farm around me and the spark of imagination that came with that seeing. I imagined both the past and the future of that very real place, in the context of the relationship with my brother in the moment, my uncle and grandfather in the past, and the generations that will come after me. From that sympathy grew an affection that exercised a far greater pull on my soul than anything America’s capitol with all its power, grandeur, and prestige had to offer.

While Thoreau, Borsodi, and the Nearings (along with contemporary agrarians, homesteaders, and artisans) all have diverse means of expressing their understandings and motivations for what they do, I believe what unites them all is that power of affection.

Each had an imagination rooted in a specific, tangible connection that allowed them see the world as a different and better place. It is in that kind of affection that the awakening from a life of quiet desperation begins.

It is that kind of affection that has changed the world before and it just may be that kind of affection that once again will change the world afresh.