It seems that when Donald Trump and his Republican enablers are able to seat a sixth right wing justice on the Supreme Court, our Lord Jesus will be doing backflips in heaven in pure ecstasy over this triumph for the Kingdom of God.

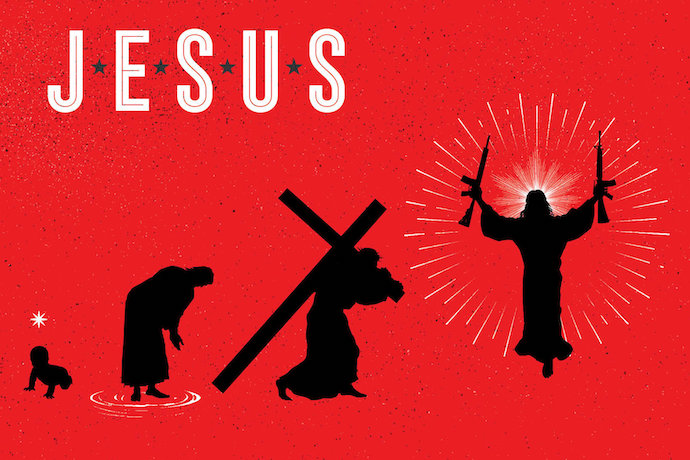

Republican Jesus: How the Right Has Rewritten the Gospels

Tony Keddie

University of California Press

October, 2020

The question, of course, is how did so many Christians—the vast majority among the 65% of Americans who still identify as Christian—come to believe that Jesus himself identifies as a Small Government conservative, i.e., a fervent fan of free market capitalism and the sworn enemy of sexual minorities, pushy immigrants, and poor people who expect the government to take care of them?

This is the question historian Tony Keddie sets out to answer in his bracing new book, Republican Jesus: How the Right Has Rewritten the Gospels. [Read an excerpt from the “Family Values” chapter here on RD — eds] Scholarly but accessible and gracefully written, Keddie’s study first introduces the figure of Repubican Jesus through the lens of Killing Jesus, the bestselling 2013 book by Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard that was subsequently made into a National Geographic film by Ridley Scott. [In fact, Tony Keddie first exposed the anti-Semitism of the Reilly/Dugard book in here on RD.]

Keddie then traces the formative influences behind this strange figure before concluding the book with a granular discussion of specific Republican Jesus “positions” on issues ranging from family life and sexuality, to charity, taxes, guns, immigration, climate change, and even Zionism. He illustrates how the Christian Right gaslights Americans on each and every one of these.

It’s important to note right away what this valuable book is not. It is not the too-familiar “they’ve got it wrong, but we get it right” plea made by many progressive Christians, who do their own share of selective proof-texting (I plead guilty myself). Keddie himself leans progressive, but he doesn’t want to let progressives off the hook for the many bits in Scripture that are irreducibly problematic.

To my mind the book’s most valuable material is found in Keddie’s middle section, where he expertly identifies the historical currents that feed conservative Christian ideation. Whereas many historians oversimplify by identifying Calvinism as the Ursprung of free market capitalism, Keddie more precisely singles out Arminianism, the deviation from orthodox Calvinism that reserved some room for human effort in the work of salvation. He pinpoints the crucial contribution of Hugo Grotius, whom the Dutch government locked up for his Arminian heresy, in laying the legal groundwork for unrestricted pursuit of private gain and the exploitative merchant capitalism of the Dutch East Indian Company.

Fast forward to the challenge of the Great Depression, when Big Business desperately needed to save its credibility and fight back against Roosevelt’s bold New Deal programs. Here Keddie highlights the little-known but hugely effective James Fifield, an L.A.-based Congregational minister who was able to marshal a wide array of corporate sponsors for a nationwide Spiritual Mobilization targeting unions and (alleged) creeping socialism.

Fifield’s contribution overlapped with the equally useful service to corporate power supplied by Abraham Vereide, union-busting founder of The Family (a.k.a. The Fellowship), the shadowy network behind the National Prayer Breakfast that Jeff Sharlet has documented so well. It hardly needs saying that the Trump family’s favorite minister—the positive thinking (and also union-hating!) Norman Vincent Peale—was also very much part of this mix.

Dwight Eisenhower became the conservative crusaders’ tool in getting “In God We Trust” on all forms of currency and getting the words “under God” into the Pledge of Allegiance. Suddenly replicas of the Ten Commandments were popping up in public spaces all over the country, thanks in part to Fifield’s wealthy Christian buddy Cecil B. DeMille, who just happened to be promoting his blockbuster 1956 film. Mounting legal challenges to these gross violations of church-state separation merely fed the flames of still more Christian nationalism. This of course was also the era marked by the rise of the people John Fea has dubbed “Court Evangelicals”: Billy Graham, of course, followed by Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson and the rest of the too-familiar crew.

Those of us who thought, or who hoped, that rightwing Christianity had hit its high water mark during the Reagan years clearly understimated this movement’s capacity to keep bouncing back. Keddie does an admirable job of showing how Trumpism combines “an allegiance to many of the traditional ‘family values’ positions of the ‘old Religious Right’ with the Tea Party’s resentment politics and the Prosperity Gospel’s glorification of wealth.” Keddie also offers a good answer to those who claim to be puzzled by the marriage between pro-business conservatives and religious conservatives; in fact, the entire book illuminates the extent to which today’s Religious Right is itself already the product of decades of careful cultivation by corporate interests.

While the issue-by-issue discussions in Keddie’s third section lack some of the voltage of the historical analysis, he does demonstrate his considerable theological chops here. Perhaps it comes as news that many Christians believe Jesus urged his disciples to arm themselves? Well, here you will find the firm scriptural foundation for Second Amendment rights! I value this part of the book for being especially clear about the deeply anti-Semitic basis of so-called Christian Zionism. In fact, Keddie is clearsighted throughout on the anti-Semitic core of the conservative Christian project. This vileness is completely of a piece with the sickening misogyny and anti-Black racism that have long marked white Christian nationalism.

Because of the way religion works, there’s not the slightest chance that white nationalist True Believers will ever let go of their Republican Jesus, let alone their fictive idea that the country was founded by Christians who intended to create a Christian country. It does no one any good to mock them, but it will do all of us a great deal of good to use our votes and our voices to take away their outsize power.