On Wednesday, January 6, I, like almost everyone else in America, watched as a mob of predominantly white domestic terrorists stormed the Capitol, in an attempt to prevent the Senate from certifying the electoral college vote in favor of Joseph Biden, a claim that, at its core, is based on the idea that voter fraud was committed by Black and Brown voters. Many of the insurgents bore flags specifically referencing Christianity. There were the Jesus 2020 flags, which resemble Trump banners; flags with the the ichthys, the Christian fish; an American flag that read “Make America Godly Again”; a banner proclaiming, “Jesus is my Savior” on one side, and “Trump is my President” on the other; as well as the “official” Christian flag with the red cross against a blue background.

However horrifying I find the spectacle of white Christians storming the Capitol in hopes of keeping Donald Trump in power, I do not find it at all surprising, because I grew up in the Christian nationalist movement. Growing up I came to understand firsthand that many Christian nationalists view people who don’t practice their form of Christianity as illegitimate. I also came to understand how racism is ingrained in the teachings of the white evangelical church.

I was born in the mid-1970s, soon after the birth of the modern Religious Right, which came into power initially using school segregation as a wedge issue. When I was five, my father became a born-again Christian and a follower of RJ Rushdoony, the founder of Christian Reconstructionism, the modern Christian nationalist movement. Christian Reconstructionists believe America was founded as a Christian nation, with no separation of church and state, Dr. Julie Ingersoll explains in her seminal work, Building God’s Kingdom. They believe the Bible is literally true and dictates every aspect of Christian life. According to their interpretation of the Bible, Ingersoll explained in an email, women are ordained to subservient roles:

“Reconstructionists put forth what they called a ‘biblical worldview’ with a long-term strategy to bring it to bear on every aspect of culture. The key tool they developed for this was the Christian school movement—and later the Christian homeschool moment. It’s not that there weren’t others who helped build those but the early legal work, the theological justification and the earliest curriculum came from them.”

All of this resonates with my own experience. I was raised in Mississippi, which only recently retired the Confederate flag, and has more private schools than any other state. Growing up I was educated in an all-white Christian school, like those championed by former Secretary of Education Betsy Devos via her push for vouchers and school choice. My family claimed to be “not racist,” yet I was educated alongside the grandchildren of the lawyer who defended Emmett Till’s murderers saying, “I hope every last Anglo-Saxon one of you has the courage to set these men free.” Each morning after my peers and I pledged allegiance to the Christian flag, we learned, via Abeka textbooks, that America was founded as a Christian nation; that the Trail of Tears wasn’t bad because God used it to convert many “Indians”; that Islam was a violent religion; that Jewish religious leaders had plotted to kill Christ; and that most slaveowners were kind to the people they enslaved, and furthermore that they had “saved” those they enslaved from a culture that worshipped the devil by converting them.

It’s important to note that my early educational experience is not an anomaly among evangelicals—Abeka curriculum is used in roughly 27% of non-Catholic Christian schools and in the homeschooling movement. Abeka’s founders, Arlin and Beka Horton, have dedicated their lives to creating an authoritarian version of education promoting fundamentalist viewpoints. “The result,” Ingersoll explains, “has been [that] a broad swath of white American evangelicalism raised on conspiracy theories, anti-government sentiment, a hostility to democracy and notions of social equality, a theological version of American history, and the rejection of science. All of which primed (evangelicals) to be responsive to the insurrection attempt.”

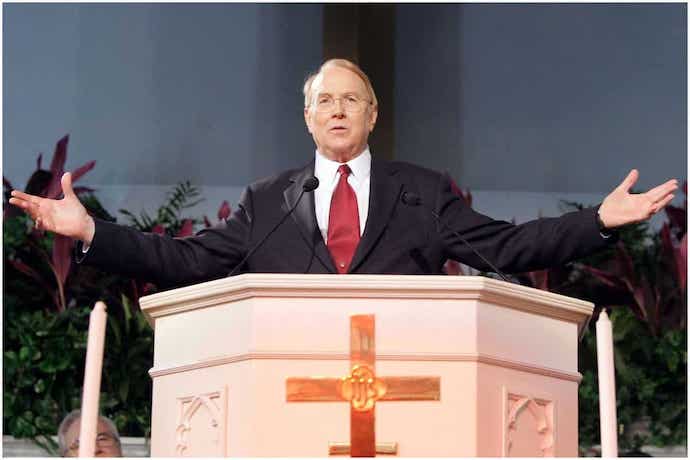

Like most Christian Reconstructionists, my father was a fervent believer in religious freedom; when, that is, it was understood as legal compromises excusing individuals and groups from laws and regulations that would otherwise apply to them on faith-based grounds. My father’s religious freedom dictated how I was educated, how I dressed, who I could interact with, and which media I consumed. I wasn’t allowed to listen to “secular music” or even wear pants until I entered puberty. If I failed to conform to my father’s exacting expectations, he would beat me with a yardstick, following the teachings of Focus on the Family founder James Dobson, whose best-seller Dare to Discipline advocated controlling children in public by squeezing a small muscle in their neck and beating them into submission with a rod or a belt.

Like most Christian Reconstructionists, my father was a fervent believer in religious freedom; when, that is, it was understood as legal compromises excusing individuals and groups from laws and regulations that would otherwise apply to them on faith-based grounds. My father’s religious freedom dictated how I was educated, how I dressed, who I could interact with, and which media I consumed. I wasn’t allowed to listen to “secular music” or even wear pants until I entered puberty. If I failed to conform to my father’s exacting expectations, he would beat me with a yardstick, following the teachings of Focus on the Family founder James Dobson, whose best-seller Dare to Discipline advocated controlling children in public by squeezing a small muscle in their neck and beating them into submission with a rod or a belt.

When I was 15, despite never having been in trouble with the law, my parents sent me to a fundamentalist reform school in the Dominican Republic which practiced conversion therapy, recommended by James Dobson’s Focus on the Family. The reasons my parents chose to send me away are complicated, but basically amounted to my having different beliefs than they did, including the right to have autonomy over my body. When I refused to be beaten, my father equated my refusal with rebelling. My parents were also unwilling to accept my emerging sexuality. At the time I had only been involved with boys, but I had told them I was also attracted to girls.

My school, Escuela Caribe, like most troubled teen facilities, utilized harsh confrontations, public humiliation, isolation, forced exercise, and deprivation of privileges to purportedly rehabilitate and reform me and my friends. We were physically, sexually, and emotionally abused, and since we were at a Christian school, we were made to feel as though these punishments were ordained by Jesus.

Escuela Caribe operated on a hierarchy, with a male director in charge, the ultimate authority. Students lived in houses controlled by housefathers. We were taught that this reflected God’s ordained structure for the home, with the father in charge. We were made to repeat the mantra, “the housefather is always right,” which kept us from questioning the ways we were mistreated.

At the school, sexual contact between students was for the most part prohibited. When a girl I knew was caught kissing a boy, both were punished. We students were taught that queerness was the same as bestiality or pedophilia. Once I was punished for holding a friend’s hand while she was crying; the staff member in charge accused me of being too intimate. The school operated on a level system, meaning to earn basic privileges like time alone, we students were coerced into surveilling our peers. When I became what is known as a high-ranker, I was forced to supervise lower-ranking students during showers, checking to make sure they soaped their pubic hair and underarms. The housefather in charge claimed he gave me the assignment because one of the girls “smelled.” At the time I was unable to question this task, because the housefather was always right. Now I wonder if this assignment was also a form of aversion therapy.

Many of the Christian staff had ingrained beliefs regarding race. I was discouraged from being friends with a boy who was biracial. Once, when two adoptee students, one Black and one brown, ran away, they were caught and beaten and put into solitary confinement before being forced to dig a dirt pit while wearing plastic sandals. None of us was even allowed to look at them.

As an adult, I helped shut my school down, but it reopened. Its current iteration is endorsed by Mike Pence.

I no longer talk to my parents. I no longer consider myself a Christian, partly because I consider members of the modern white church to be ‘lukewarm,’ as the Bible puts it, afraid to speak out against the more radical members of the white evangelical church at large, like the ones who ran my school and espouse hatred of Muslims, immigrants, Blacks, feminists, Jews, and members of the LGBTQ community.

Growing up, I learned that Jesus said that the second greatest commandment was to love your neighbor as yourself. However, over the past four years, I’ve been horrified to watch protections for the LGBTQ community and others be erased in the name of religious freedom. In 2020, 3 out of 4 white evangelicals voted for Trump despite the Muslim Ban, despite child separation, despite the assault on the environment, despite the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh, who was credibly accused of sexual assault, despite the unchecked spread of COVID-19, which disproportionately kills members of the Black, Latinx, and AAPI community, despite the disproportionate numbers of Black men and women murdered by our police.

The Sunday before the 65th anniversary of Emmett Till’s death, Jacob Blake was shot seven times in the back by a white officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in front of his children. There was no national outcry from white evangelicals. Instead, Christian crowdfunding site GiveSendGo hosted a fundraiser to support 17-year-old domestic terrorist Kyle Rittenhouse after he killed two Black Lives Matter protesters and wounded a third. Again, having grown up in the Christian nationalist tradition, none of this is surprising. As Katherine Stewart, author of The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism, explained to me recently:

“Some of the extremists involved in the assault on the Capitol on Jan 6th are either explicitly Christian nationalist or Christian nationalist-leaning, adhering to the idea that America was founded as a so-called ‘Christian nation’ and asserting that it’s their ‘right’ to ‘take it back.’ So the ideology of Christian nationalism played a part in organizing these groups and individuals and spurring them to action. We also can’t overlook the role of religious messaging platforms and religious leaders who were involved in riling up this cohort long before the events of January 6th. The December 12 Jericho March in Washington, D.C. was promoted as a ‘Stop the Steal’ event, with religious figures asserting the election results were somehow fraudulent.”

Stewart explains how, at a higher level, key Christian nationalist organizations were instrumental in preparing the ground for the assault by feeding the conspiracy narrative of a “stolen election”:

“The Conservative Action Project, which is associated with the Council for National Policy, demanded investigations of the spurious and baseless allegations of election fraud. Sponsors of the January 6th rally, which was predicated on the baseless lie of an illegitimate election, included groups like Phyllis Schlafly Eagles, Moms for America, and Turning Point Action, the political action arm of Turning Point USA, a right-wing campus group headed by Charlie Kirk.”

In the ensuing days since the siege, I’ve watched videos of a white man in a QAnon shirt chasing a Black police officer, Eugene Goodman; of a crowd of white men beating a police officer with an American flag; of a crowd of white men crushing a police officer’s head as he tried to block them from entering the Capitol; and of white police officers allowing members of the mob past barricades, even posing for selfies with the mob once they were inside.

I’ve watched videos of Christians engaging in praise and worship before they stormed the Capitol, of Jacob Chansley, the ‘QShaman’ wearing Viking horns, leading a group prayer from the Senate dais, saying “Thank you, Heavenly Father, for being the inspiration needed to these police officers to allow us into the building, to allow us to exercise our rights, to allow us to send a message to all the tyrants, the communists and the globalists.”

I’ve watched President Joe Biden declare white supremacy to be a national threat to democracy. I’ve heard calls for unity from many of the same Republicans who fanned the flames of the insurrection and later booed Representative Cori Bush for denouncing white supremacy. I’ve seen mixed reactions from the white evangelical church regarding Capitol violence. I’ve watched Republican senators rally against impeaching Donald Trump for his role in inciting the riot.

Given my upbringing, I worry that neither the white evangelical church nor the public at large understands the danger that Christian nationalism poses to democracy.

It all feels like echoes of my past. Once again, I, along with everyone else in America, am being told to not question why the Capitol Siege happened, because the housefather is always right. Except this time, the housefather is the 45th president, and elected Republican officials his enablers.