I don’t like Beyoncé in the way that some people do—I am not a bee in the hive. I do, however, recognize greatness when I see it, and Beyoncé’s “Formation” is just that.

Beyonce’s African and “Creole” ancestors haunt the song and its video. “Formation” is diasporic, it is indebted to its predecessors, and it is firmly rooted in the present—a culmination of black artistic expression.

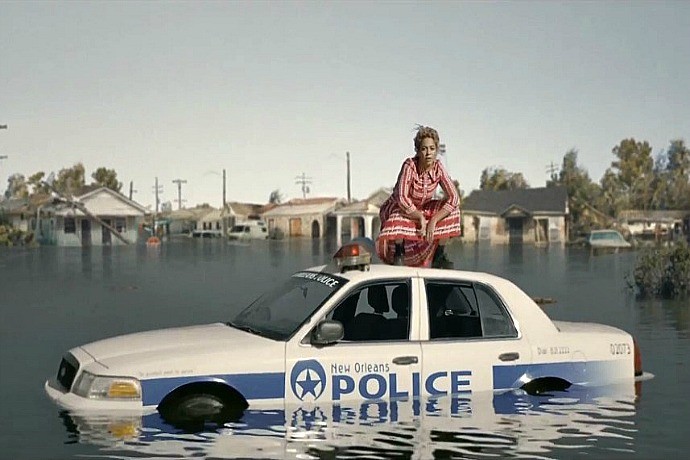

The video opens with a question: “What happened after New Orleans?” The voice does not belong to Beyoncé, but to Anthony Berr or “Messy Mya,” a New Orleans bounce music artist who was gunned down in 2010. Beyoncé is sending a clear message that the violence in New Orleans —and across the world—needs to stop.

But Beyoncé’s question is more than just an homage to Messy Mya, it is an accusation: What did happen after New Orleans?

Coupled with the visual of Beyoncé squatting atop a police cruiser in the middle of a flooded neighborhood, Messy Mya’s question becomes an obvious allusion to Hurricane Katrina. Beyoncé starts by forcing her audience to confront the reality of black death and black drowning. The opening question is rhetorical—there is nothing “after” New Orleans. Black people like Mya continue to die of gun violence at alarmingly high rates, and New Orleans is still “underwater.”

Black deaths are neither coincidental nor a matter of ill fortune. Mya’s murder is linked to the Katrina catastrophe because both are the products of a system that fails to adequately protect black lives. The New Orleans levees were not built for worst-case scenarios; the justice system is not built fairly and impartially.

If Mya haunts the beginning of the video, then ancestors—both named and unnamed—haunt the remainder of the production.

In African culture—by no means monolithic or simple—people have a complex relationship with deities and the dead. Gods and ancestors are active in the world: they can be consulted and petitioned, dissatisfied or approving. Beyoncé’s work—like the African cosmologies that inform it—reminds us that , as scholar Joseph Olupona writes, “forebearers need their progeny in order to sustain themselves […] as much as the living need blessings, wisdom, and grace from their predecessors.”

It is important to note, however, that the notion of ancestry differs among diasporic and indigenous African people. Olupona describes ancestral veneration as a process that begins at death, adding that a common requirement for ancestry is dying a “good death.” Instead Beyoncé’s piece invokes the voices of people who have died violent, unspeakable deaths. In one scene, a black man break-dances in a convenience store. Beyoncé’s audience does not need to be reminded that Michael Brown was accused of stealing from a local convenience store and was shot in the back because—according to Officer Darren Wilson—he resembled a “demon.”

Beyoncé transforms Brown’s supposed crime into a celebration of black dance. The man dancing in the convenience store affirms the spirit of slain black youth like Brown.

Beyoncé’s piece not only transforms sites of violence, it transgresses boundaries. Black women gyrate in what looks like a “big house,” breaking the rules in “Massa’s” quarters and desecrating white-designated spaces. Similarly, Beyoncé herself desecrates pop culture. She takes the colloquial term “slay” and turns it into an anthem of resistance.

To “slay” means to dance, it means to live, it means getting in formation and surviving. It means having “negro noses with Jackson Five nostrils,” it means eating food at Red Lobster—a chain formerly chaired by a black CEO.

The most provocative imagery in the piece is the preacher and the priestess. These two figures are juxtaposed with one another, evoking muddled feelings of uncertainty and awe. Just as “negro” and “Creole” are mixed—though the nature of that distinction should be questioned—so black Christianity and non-Christian practices are mixed.

Religious and cultural hybridity are part of the African experience, part of the African American experience, and part of the black experience. The fact that Beyoncé plays the figure of the priestess throughout, and a zealous male plays the figure of the black preacher should not be overlooked. These two figures are the heart of the black community. Black women have always been healers and “sha-women.” Black women have always possessed power and wielded it in unconventional ways. Black women and black men—like the gods of the African pantheon—find relief in androgyny.

Beyoncé the priestess is possessing us—much like her ancestors possess her.

Beyoncé reminds us that Martin Luther King, Jr. was more than just a dreamer, that a black boy’s fluid movements can disarm brutal police officers, and that the male-female dichotomy is a false one.

As Beyoncé sits on a stoop, nodding her head and directing the formation of black women who dance in the street, the refrain echoes: “let’s get in formation.” The soundalike is a play on words: let’s get organized–and let’s get informed. In the empty pool, there is a cut back to the hooded child dancing in front of the police officers. Beyoncé has transferred her power of possession to the boy—the apparition of young Tamir Rice.

The officers raise their hands in submission; they are now under Beyoncé and the boy’s spell. The power of Beyoncé, black ancestors and black bodies becomes manifest.

“Formation” is a spiritual call for black resilience and resistance.