A few years ago, the idea of a “celebrity Jesuit” would have puzzled most Americans. That was not only before the election of the first Jesuit pope, but also before Fr. James Martin began appearing on The Colbert Report, and before his books on saints, spirituality and prayer ascended the best-seller lists.

Today, Martin occupies a unique place in religious media: still working a day job as the editor-at-large of America magazine (where I’m an occasional contributing writer), he’s also become a go-to explainer of Catholic issues to both religious and secular audiences. He’s so successful in this role that in April of this year, he took up yet another job when he was invited by Pope Francis to be a consultor to the Vatican’s Secretariat for Communications.

In the past few years, however, even as Martin’s profile has grown, it has also included a focus on one of the Catholic church’s most marginalized groups, the LGBT community. Martin describes this as an “informal ministry,” conducted through articles, conversations and social media, and it expanded after the June 2016 shooting in Orlando, Florida when Martin was dismayed that Catholic church leaders failed to acknowledge the targeting of LGBT people in the Pulse massacre. His Facebook video posted the day after Orlando has over a million and a half views.

The scope of his outreach is still so unusual for a Catholic priest that Martin was honored by the church reform group New Ways Ministry in October of last year.

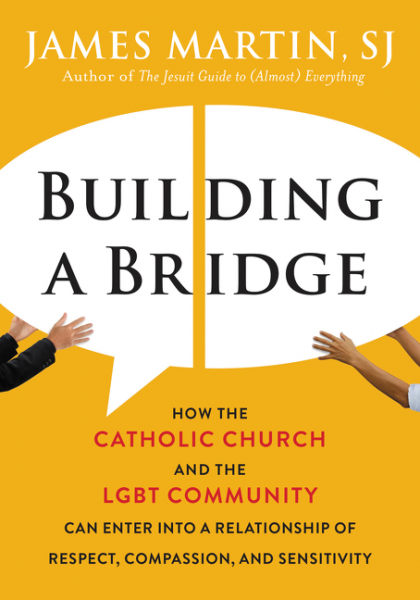

Building a Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LGBT Community Can Enter into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity

James Martin

HarperOne

June 13, 2017

The talk he gave at that gathering has now been expanded into a book, Building a Bridge. Martin’s collection of the expanded talk and scripture meditations for LGBT Catholics even comes with an unusual set of endorsements from cardinals, bishops, and New Ways Ministry founder Sister Jeannine Grammick, who was investigated by the Vatican for her work with LGBT Catholics in 1999. At a time when Catholic school teachers and lay ministers are still regularly being fired for being LGBT, endorsements from church higher-ups for a book that advocates pastoral outreach to LGBT Catholics comes as a surprise. But it’s also indicative of Martin’s unique position in the church: respected by everyone from Vatican officials to activist women religious to secular journalists to his massive social media following, he may actually be in a position to gently influence the way LGBT people are treated by the institutional church. We spoke in May.

Kaya Oakes: You mention in the book that you have an “informal ministry” to LGBT Catholics. Can you talk about how that came about and what that looks like—because with this book coming out, that might become less informal?

James Martin: It’s similar to the kinds of ministries that other Jesuits, priests, members of religious orders and lay pastoral associates have in parishes. For example, some people who come to me for spiritual direction might be LGBT. Some people who seek me out after Mass, or on a retreat, or after a talk, might be LGBT. Some people who contact me through social media might be LGBT. It’s grown since I started to write more online and in America magazine and be quoted about these issues. People may feel more comfortable knowing I’ll be more welcoming. In the process, I’ve gotten to know a lot more about that kind of ministry, even though it’s not a formal ministry. For example, I’ve never worked in an LGBT outreach program in a parish, or done seminars, or anything like that. But I feel like I’ve gotten to know a lot about the needs and desires of that part of the Catholic church.

The book and the original talk are both focused on the idea of a “two-way bridge.” There’s plenty of reason for LGBT Catholics to recognize the need for the church to show more “respect, compassion and sensitivity” toward them, but why does the community need to show that to the church?

The first thing to say is that the onus is definitely on the institutional church, because not only do they have the power, but because LGBT Catholics are the ones that have felt marginalized for so long. By the same token, those virtues are helpful for the LGBT community, because those are Christian virtues. Respect is important for anybody in dialogue with bishops or laypeople or anyone. And I talk about that in terms of needing to simply respect not only the office but the individuals, bishops for example. Compassion is trying to understand the bishops in the complexities of their ministries, which is simply a Christian thing to do, and a smart thing to do. Sensitivity is understanding the way different levels in the church speak with different levels of authority, so as not to mistake what your local parish priest says for a papal encyclical. Bishops are going to read this book too, and they’re going to want to know that the LGBT community can interact with them in a respectful way as well. But the basic answer is that those virtues are Christian virtues.

One of the things that always comes to mind is Martin Luther King, and the way he counseled people who were facing persecution. And I think of those people sitting at the luncheonette counters in the South, and the way that they were always respectful, even when they were being persecuted. That’s a good model for anyone. Those photos always comes to mind when people ask that question. It’s powerful for me, and that model of Dr. King’s response to persecution stands the test of time.

There has been some progress in relations between the church and LGBT Catholics, but there’s also been a lot of backlash, particularly in the forms of firing gay church employees (most recently at a Jesuit high school in Chicago). How do these firings complicate the idea of a back-and-forth relationship, because a lot of these lay ministers are Catholic?

I don’t know much about the school in Chicago, but it complicates that relationship immensely, because the firings make LGBT Catholics feel like they’re the only ones whose moral conduct is being put under a microscope. The problem is that it’s highly selective, and we don’t police the lives of straight or married Catholics in the same way. Otherwise, we would have to fire every divorced and remarried Catholic who had not gotten an annulment; every Catholic who’s divorced, because that’s against what Jesus teaches; every Catholic who’s engaging in premarital sex, and every Catholic who has a child out of wedlock. And people say, “We can’t get rid of all those Catholics, that would be excessive.” The question is why just focus on LGBT people, and that’s a clear example, in my mind, of what the Catechism calls “unjust discrimination.” If you want to make adherence to church teaching required in terms of employment, then you would also have to fire all Protestants because they don’t believe in papal authority, all Unitarians because they don’t believe in the Trinity, all Jews because they don’t believe in Jesus, and all agnostics and atheists because they don’t believe in God. Those are all church teachings. People sometimes roll their eyes, but that’s the whole point. We’re being highly selective in whose conduct is being looked at.

As a person who’s reached a certain platform in the media and can write books like this, what advice would you give younger LGBT Catholics who are afraid to speak out because they worry about their own careers or vocations—for example, if they’re a seminarian, or teaching at a Catholic school or college?

I would say I still am very careful about what I say in terms of respecting church teaching, respecting the hierarchy, and respecting where other people happen to be in their approach to these topics. But by the same token, there’s always a role for prophecy, and sometimes speaking uncomfortable truths. And that’s where discernment comes in. “What is the thing to do in this particular situation?” is the classic Jesuit question.

The other way of framing it is what my moral theology professor James Keenan used to say, which is that these questions are often between justice and fidelity. Justice is speaking out in favor of a persecuted group with fidelity to whatever organization that you are a part of. And, again, the key is discernment. When is the right time to speak, what are the right issues to take up, how does one frame them, which words do you use, whom do you challenge and in what way. What I try to do in the book is to help us find common ground and also push the envelope as much as I can. Most likely, some LGBT Catholics will think I have not gone far enough, and some bishops will think I’ve gone too far, which is probably the right place to be.

A couple years ago I interviewed Richard Rodriguez, and he says that as a gay Catholic, his liberation came from the liberation of women—that gay Catholics are striving for equality in the church in the same way women are. What do you think of this idea that there’s a common struggle in the church between women and LGBT people?

It’s an interesting parallel. I always look to the work of feminist theologians to help me understand how Scriptures are interpreted through a patriarchal lens, with an eye to pushing women out, or down, or excluded. That spirit, which I imbibed during my graduate theology studies, has really helped me to appreciate the way that the church can subjugate people, intentionally or unintentionally.

But by the same token, that analogy fails, because LGBT people are the most marginalized people in the church today. And even though many women feel marginalized, you still have conferences at the Vatican on women, or Women’s Day at the Vatican. You don’t have an LGBT Day at the Vatican.

While Pope Francis has made great strides in what he’s said and even in his use of the word gay, we are so far from that still. It’s easy to say I want to have a Mass for women in the parish, or a women’s book group, and there are obviously still big questions that women have about their role in the church. But for the most part, that kind of outreach is accepted. In most parishes, however, that kind of outreach for LGBT people needs to go through multiple layers of approval, to the point where you can’t even use the word LGBT. They’ll use something like “Spectrum” or “Welcome Ministry.” It has to be so coded that it doesn’t ruffle any feathers, and that’s not the case for women. And that’s very sad. To me, LGBT people are sometimes treated like lepers. One of the things I’ve learned in this informal ministry is the unbelievable things priests, sisters, brothers and lay associates will say to LGBT Catholics. It’s just horrifying.

One of the great shocks in the last few months is that this ministry is not just about the LGBT person, but about a much greater population. It’s about their grandparents and parents and aunts and uncles and brothers and sisters and friends. I was giving a talk at the Catholic center at Yale on Jesus, and afterwards this woman came up to me who looked like she was out of central casting for grandmother roles. She leaned over, and I thought she was going to say, “My favorite saint is Therese of Lisieux,” or “I’m going on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land,” and she said, “My granddaughter is transgender and I love her so much. And my greatest hope for her is that she feels at home in the Catholic Church.” And I thought, this issue hits not just the LGBT Catholic, but a whole population of people who know and love LGBT Catholics. What’s more, for millennials, even if they’re not LGBT, many don’t want to belong to a church that excludes their LGBT friends. That’s a non-negotiable for a lot of people. While we might think the issue affects just a small percentage of Catholics, it actually affects a great many of them. That was kind of shocking to me, frankly.

Because more and more people are out, that means more and more family members and friends are affected. It’s not that there are more LGBT Catholics, but that they are more well-known, which means this is a bigger issue for more people. It’s a bigger issue for the church than what the percentage of LGBT Catholics might indicate. Twenty years ago, that grandmother might have turned up her nose at the question of transgender people, but now that her granddaughter is one, it’s part of her life, and she cares about it.

You often address the problems of trolling and hateful comments in your social media posts. Is this particularly bad among Catholic audiences, or is there something particularly bad in religious media in terms of the reaction people have to stuff that pushes the envelope?

The people who are trolls in the Catholic world think they have God on their side. That makes them much more confident about condemning people and putting their two cents in. They feel anyone who disagrees with them is a heretic or a bad Catholic. What’s more, they feel that it’s their responsibility to tell you that you’re wrong because they’re supposedly saving your soul, despite what Jesus said about “Judge not.” I used to get more upset about these things until I realized a couple of things. Number one, not everyone’s going to like you. Number two, engaging with these people in arguments is often fruitless. Number three, a lot of times they refuse to listen. And number four, a very small percentage of them are actually crazy.

There’s a great scene in a movie called The Trouble with Angels from the 1960s. It’s about a Catholic girls’ school outside of Philadelphia. There’s a scene where Rosalind Russel, who’s the Mother Superior, is arguing with Jim Hutton, who plays an educational consultant. And Jim Hutton says, “The finest educational minds in the country happen to be on our side.” And there’s shot of Rosalind Russel with a huge crucifix behind her, and she says, “God is on ours.” And that’s how I often see those things. They think they have God on their side.

The comments I get about LGBT issues are the worst by far. It is just shocking how many people think just being LGBT is a sin, how many people think they need to be condemned, and how many people who say “Hate the sin and love the sinner,” while they’re clearly hating the sinner. But sometimes when I get into public discussions with questioners, I’ll say, “What about the LGBT people you know?” That usually stops the conversation, because often they don’t know any. The anger I see about this issue on my Facebook page and on Twitter shows it’s a public demonstration of why it’s hard for LGBT Catholics to find a place in the church.

How are you feeling as the book gets close to its release?

I’m just as excited about the second part of the book, which is a series of Bible passages and meditations and reflections for LGBT Catholics, as I am about the first half of the book. The book is not only the invitation to dialogue between the institutional church and LGBT Catholics, it is a series of spiritual resources that I hope finds its way into the hands of struggling LGBT Catholics, particularly young people, who need to be shown that in the Old and New Testament, there are places where they can find comfort, and where the Spirit can speak to them. Honestly, I’m really happy that it was able to find its way into print finally. I am at peace with this book.