In a strange way, I envy the people who were raised as evangelical Christians in the 1980s and 1990s, because many of them got to experience This Present Darkness in a way I never could. For the uninitiated, This Present Darkness is a horror novel by Frank Peretti published in 1986, at the height of the Satanic Panic, whose paranoid themes are depressingly familiar almost 40 years later. The plot revolves around a left-wing conspiracy that targets the small town of Ashton in what appears to be the first move toward a secular-progressive takeover of the government, the media, and the entire culture. But behind the scenes, the real battle is being waged between the angels who are trying to protect the town and the demons who are trying to destroy it. The faith of the God-fearing Christians of Ashton, who contribute to this battle every time they pray, becomes the deciding factor in the spiritual war raging all around them.

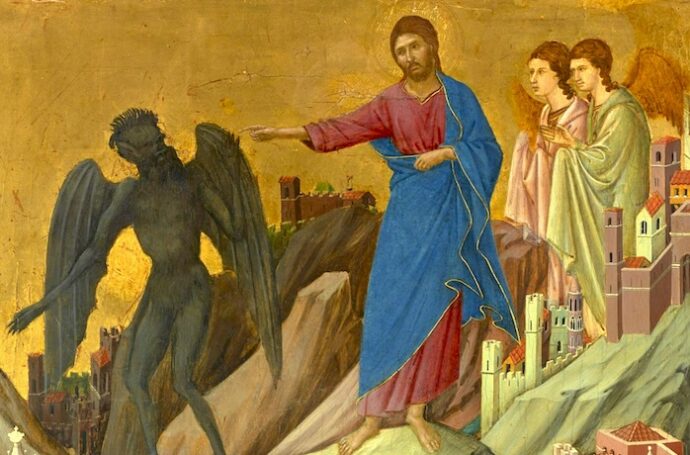

I had already deconverted from Catholicism by the time I came across the book in 2001, and had no idea that this schlocky, paint-by-numbers thriller had sold millions of copies and helped create the modern evangelical worldview. What I envy, to a degree, is the way in which this book must have made its readers feel, at least for a while. Whereas the later, and even more popular, Left Behind series issues a threat about the end times, Darkness makes an enticing promise: no matter how powerless a person might seem in this world, their faith is part of a larger, invisible conflict, involving noble angels and hideous, cunning devils. Peretti further suggests that the world we live in is an ugly veneer to the reality that lies beneath, where good and evil are clearly defined, and the pressing materialistic issues we wrestle with don’t really matter. After all, the book’s title derives from this passage in Ephesians:

For our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places (Eph 6: 12, NRSV).

Not surprisingly, that line comes a few verses after this gem: “Slaves, obey your earthly masters.” Interpretations vary, but the message many people seem to have gotten is that we shouldn’t sweat the justice stuff in this world. Instead, we should focus on what’s really important: faith in the supernatural realm. I would have loved to feel that kind of confidence and clarity in my teenage years, and clearly there are plenty of adults today who crave the kind of authoritarian, reality-denying certainty that the spiritual warfare model offers.

Progressive Christians might try to dismiss Peretti’s literal understanding of angels and demons as a fringe element, and I wish they were right. But their fellow Christians in the United States have spoken, not only in sermons and books, but in votes, political donations, and culture war movements. The majority of voters who identify as Christian supported Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020, and will do so again this year, and their use of spiritual warfare to rationalize their decision has become so commonplace that it no longer warrants a second glance in the media.

The examples of angels-versus-demons rhetoric are too numerous to list, but it’s worth starting with Trump’s own spiritual advisor, Paula White, who’s been saying for years that a “demonic network” has deployed a “strategy from hell” against the former president. Pastor Franklin Graham has suggested that Trump’s enemies are possessed by demons, while the Trump campaign has promoted the idea of “prayer warriors” fighting the forces of Satan. Not surprisingly, many Christian leaders promised that the January 6 insurrection would be a reckoning with the “demonic influence” that “stole” the election of 2020, and there’s strong evidence that “figures within the Trump White House were strategizing with” the prayer warriors of the New Apostolic Reformation in the days leading up to it. At the not-so-subtly named National Gathering for Prayer and Repentance in February, Trump ally and Speaker of the House Mike Johnson joined with religious leaders to “bind the demonic forces” that threaten their puritanical vision for the United States.

How deeply Trump believes himself may be debatable, but he clearly knows his base, having astutely pointed out that they would continue to support him even if indicted for felonies and, indeed, even if he shot someone. As a result, his 2024 campaign has released an ad touting him as a messiah figure chosen by God to fight the “deep state.” And he’s gotten more comfortable using terminology that conservative Christians will recognize, like when he promised to “cast out” (i.e. exorcize) his enemies in a “final battle.”

While the prevalence of the spiritual warfare model seems clear, its actual influence on politics is up for debate. Christians on both ends of the political spectrum have an incentive to downplay it; conservative Christians often respond to criticism by claiming that they are the victims of persecution and mockery, or they deflect by claiming that liberals have simply been triggered by religious talk. Meanwhile, progressive Christians can claim that fearmongering about a cosmic battle represents an inauthentic version of the religion, and that only they, the anti-Trump faction, are the true followers of Jesus. And, of course, progressive Christians can always lob the “demonic” accusation right back at their opponents. That’s the beauty of an unfalsifiable truth claim. With no reality check, anything goes.

Recently, however, some research has emerged to illustrate the correlation between belief in spiritual warfare and right-wing politics. Fanhao Nie, a sociology professor at UMass Lowell, examined the political implications of belief in demons for his paper in Social Currents, titled “Ruled by Demons: Exploring the Relationship Between Belief in Demons and Public Attitudes Toward Donald Trump and Joe Biden.” The article drew some attention on Twitter before quietly being ignored. Which is a shame. While references to Satan and hell aren’t new to conservative politics, Nie argues that the rhetoric escalated—and became more accepted—during the administration of George W. Bush. Despite the increased use of this language, Nie comments on the “paucity of empirical research” regarding the effect of demonic warfare-talk on our deteriorating democracy.

In the study, Nie links a respondent’s certainty that demons are active in the world with an ingroup/outgroup mentality, and with a right-wing political identity. Nie’s methodology attempts to control for Christian nationalism, the ideology that aims to enforce a Christian identity for the country through laws and culture. In other words, even when taking the overtly political version of Christianity into account, the supernatural belief in demons—what Nie calls “the dark side of religion”—appears to be strongly correlated with support for Trump, and especially with hatred for Biden.

I don’t wish to overstate the significance of a single paper. Like any study, Nie’s article awaits more data, more refinement of the survey questions, and a larger sample size. More importantly, the study doesn’t prove that belief in demons causes a person to vote Republican, only that the two are correlated. At the very least, this research should challenge the experts who’ve staked their reputations on the claim that politics has somehow poisoned Christianity—an idea that ultimately serves, either intentionally or not, to deflect legitimate criticism of Christian leaders, institutions, and doctrines. (Chrissy Stroop, writing for Religion Dispatches, calls this the “‘fake Christian’ deflection.”)

With the demon belief, we have what appears to be a religious dogma influencing, sustaining, combining with, and maybe even compelling a political position, rather than the other way around. But we may never address that core issue, so long as the loudest voices in the media remain stubbornly committed to the idea that there exists a clean distinction between politics and religion, and that cynical outside forces have commandeered and polluted religion to gain power. Daniel Miller called out this trend back in 2016. And, as I have argued before, the “true Christianity/fake Christianity” model simply cannot concede that Christianity (i.e. religion) can be blamed for anything. From this perspective, religion deserves credit for the things it gets right, but everything else is merely politics, existing outside of the true practice of a given religion.

It would be far more accurate to acknowledge that, as with any religion, there are good things and there are bad things about Christianity—but the bad things are as authentically Christian as the good. And just as important, the Trump era isn’t a story of some malevolent force emerging from the void and exerting its will on Christianity. Support for Trump is merely the latest in a long pattern of mainstream Christian denominations siding with authoritarian power and finding themselves on the wrong side of history. It isn’t an accident. It was entirely predictable. In fact, it’s such an old story that anyone who is surprised by this latest iteration should probably be disqualified from sharing an opinion on the matter.

But demon belief—and its application in contemporary US politics—isn’t just troubling when taken too far. As we’ve seen, the spiritual warfare worldview carries with it the potential to warp a person’s understanding of our shared existence, providing a free pass to ignore observable evidence, which has become a real problem in the age of gaslighting, alternative facts, and “doing your own research.”

If a person wants to deny the results of the 2020 election, for example, they don’t need to find a truckload of fake ballots. They can simply assert that the election is part of a larger struggle with the forces of hell. If a person doesn’t want to take the COVID vaccine, they don’t need to organize a peer reviewed study. Instead they can declare that the jab is the mark of the beast, and that God will intervene on behalf of the faithful. Thus, any conflict, no matter how mundane, can be as dramatic as the most lurid chapter of This Present Darkness.

No matter how many examples of this nonsense we find, sophisticated experts and columnists will dismiss it all as fake Christianity. They will continue to interview Trump supporters in Midwestern diners, endlessly wondering what happened to their religion, and how good Christians could vote for a lying traitor. Above all, they will long for the day when Christianity as they understand it can emerge from this period of history and leave it behind.

But this is an election year, and we’ve run out of time for obfuscation. American Christianity cannot and must not come out of this era unchanged, unchallenged, and enjoying the same level of power and influence. Calling out Christianity and the role it’s played (and continues to play) in today’s toxic right-wing politics will not be an easy task. Christian privilege is baked into our culture, and criticism will inevitably draw accusations of anti-religious prejudice. We should be willing to take that risk anyway, because our efforts thus far to draw artificial distinctions between religion and politics, or to be overly deferential, have failed. Demons may haunt the Trump movement, but they only have as much power as we give them.