Over the same period in which advocates of reproductive justice have been fighting a rearguard effort to preserve Americans’ constitutional right to abortion care, LGBTQ advocates have fought to advance the use of more gender-inclusive language in a variety of contexts, including the context of reproduction and abortion. Aware that abortion access, while certainly a critical women’s rights issue, also affects some transgender men and nonbinary individuals, some journalists and commentators have begun to adjust their language accordingly, sometimes employing gender-neutral terms like “people who can get pregnant.” This is a good thing.

Meanwhile, this week, with the end of Roe looming, some acquaintances, friends and colleagues have privately shared concerns with me about our ability to balance concern over the frequent erasure of transmasculine people—generally speaking, those assigned female at birth, but who identify with a masculine gender identity—from the national conversation about reproductive justice with the importance of emphasizing the misogyny that clearly drives the anti-choice movement.

For my part, I don’t see the two goals as in conflict or competition with one another, and certainly not in any zero-sum sort of relationship. After all, misogyny and racism are the twin pillars of white supremacist patriarchy on which anti-LGBTQ animus—a powerful force in its own right—rests. As Jacqui Lewis recently wrote here on RD regarding the close connection between LGBTQ rights and reproductive healthcare (as well as other social justice issues): “we don’t need to choose and prioritize whose freedoms matter most.”

Reproductive justice, which covers matters ranging from abortion to fertility treatments to prenatal care and parental leave, is clearly a women’s issue, an LGBTQ issue, a racial equality issue, an economic justice issue, and an issue that affects a wide variety of intersecting communities and types of families.

At the same time, I recognize that the evolution of linguistic norms away from Victorian heteronormativity, particularly in the context of ongoing and unsettled debates about terminology, can be confusing and fraught. It may also be severely anxiety-inducing in a social and political climate as charged as ours.

As a transgender woman, I am well aware that efforts to adopt more inclusive language around reproduction are often attacked by the bad-faith transphobic actors often referred to as TERFs (trans-exclusionary radical feminists) who insist that women (meaning only cisgender women) are “erased” when phrases like “pregnant person” or “menstruating person” are used in even the most limited, individual, patient-centered contexts.

Tellingly enough, their ire tends to focus on trans women like myself—as if there were a cabal of us sitting around somewhere dictating new social and linguistic rules as a means of attacking cis women—as opposed to the trans men and nonbinary individuals who have the physiological capacity for pregnancy.

In other words, TERFs’ rhetoric and obsession with transfeminine people further contributes to the erasure of the transmasculine folks directly harmed by the Christian Right’s assault on abortion access, an erasure that should be of concern to those of us who care about social justice in general, and LGBTQ rights in particular. Meanwhile—and this point should be obvious, but in today’s climate I think it needs stating—not all transmasculine people are able to become pregnant, and neither can all cis women.

With that in mind, even though reproductive justice issues disproportionately affect women, it should be clear that tying the essential definition of “woman” to reproduction is as problematic from the Left as it is from the Right, where many openly argue that motherhood is every woman’s divinely ordained role—a role to be pursued at the expense of all others. (It’s worth noting here in passing that neither the Catholic Church nor the Southern Baptist Convention, the world’s largest Protestant denomination, permits the ordination of women.)

Both the transantagonistic Right and the transantagonistic Left tend to focus their attention disproportionately on trans women, often using the same tired tropes about predatory “men in dresses” attempting to take over women’s spaces. It seems to me that if we probe the reasons for this, as well as the connections between anti-abortion and anti-queer attitudes and politics, we’ll come away with a renewed sense of why there’s no conflict between pointing out the misogyny of the forced-birth movement and working to counter the erasure of transmasculine folks from discussion of abortion and other reproductive health-related concerns. Misogyny and patriarchy are, after all, at the heart of it.

Why is it that transphobes are so afraid of “men in dresses”? The answer is essentially the same if we ask why accusations of throwing “like a girl,” or of “being girly” for ordering a Cosmopolitan instead of a Dos Equis or a less “froufrou” cocktail, are common insults in male groups and masculine-coded spaces. One of our social pathologies is a fear of the “feminization” of men (or people society insists are “supposed” to be men). Right-wing authoritarianism always stresses hypermasculine ideals, and right-wing authoritarians also tend to focus on having babies, often fearmongering about declining birth rates and a supposed “replacement” of “us” by racially coded “others” that will destroy (white) “Western civilization.”

Why is it that transphobes are so afraid of “men in dresses”? The answer is essentially the same if we ask why accusations of throwing “like a girl,” or of “being girly” for ordering a Cosmopolitan instead of a Dos Equis or a less “froufrou” cocktail, are common insults in male groups and masculine-coded spaces. One of our social pathologies is a fear of the “feminization” of men (or people society insists are “supposed” to be men). Right-wing authoritarianism always stresses hypermasculine ideals, and right-wing authoritarians also tend to focus on having babies, often fearmongering about declining birth rates and a supposed “replacement” of “us” by racially coded “others” that will destroy (white) “Western civilization.”

From this twisted perspective, a “feminized man,” one who has “gone soft”—or, in the context of colonialism, “gone native”—is a threat to empire, to “order,” to “civilization itself.” Meanwhile, the “masculinization” of women (or people society insists are “supposed” to be women) is also perceived as a threat, but it’s one to be addressed by “real men” who are prepared to “put women in their place.” In other words, masculinist authoritarian ideology tends to place the responsibility on men simply to be “more manly” as a means of controlling and “correcting” these “wayward” women, which is another reason the “feminization of men” is a greater direct source of right-wing panic than the “masculinization of women.”

At the same time, presumably because of the implicit understanding in a patriarchal community that masculinity and maleness are “superior” to femininity and femaleness, some spaces are carved out, with varying degrees of acceptance, for “tomboys” and butch women—though they can also be subjected to harsh social policing.

The point I’m trying to get at here is that both queerness and any deviation from prescribed gender roles inevitably destabilize patriarchy, and those committed to a patriarchal social order will therefore respond to gender-nonconformity as a threat. It is precisely because of the misogyny that lies at the root of a patriarchal social order that “men” behaving “like women” receive the lion’s share of negative attention from defenders of the order, as they are viewed as abdicating their “natural” social role of enforcing the subjugation of women.

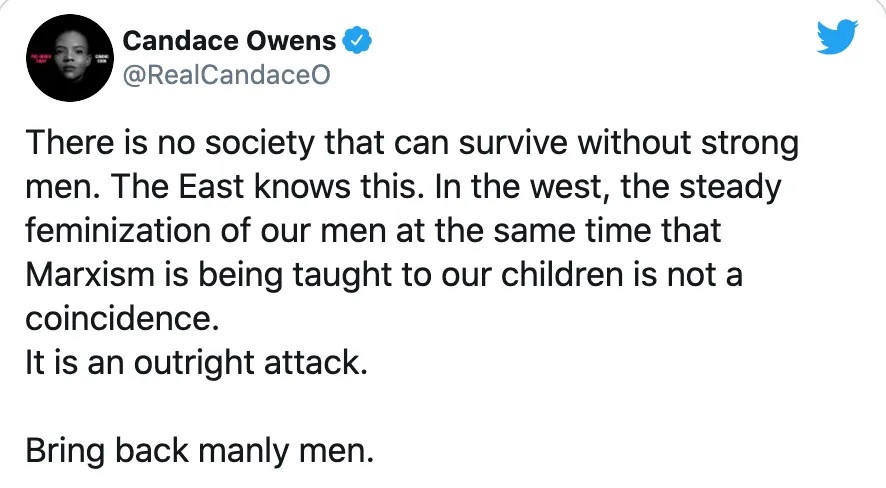

To drive home the point, just take a look at conservative responses to the November 2020 issue of Vogue featuring Harry Styles on the cover in a ball gown, including this widely publicized and derided tweet from Candace Owens:

The panic around men (and trans women) who abdicate “manliness” is one key factor in the erasure of transmasculine folks from our public discourse. Meanwhile, patriarchal societies attempt to subjugate women by depriving them of agency and autonomy over their own bodies—including and especially in the key area of reproduction.

The panic around men (and trans women) who abdicate “manliness” is one key factor in the erasure of transmasculine folks from our public discourse. Meanwhile, patriarchal societies attempt to subjugate women by depriving them of agency and autonomy over their own bodies—including and especially in the key area of reproduction.

Viewed in this context, then, it should be clear why the erasure of transmasculine people and the push to ban abortion are of a piece, both borne of the misogynistic nature of patriarchal society, and why it’s essential to fight back against both in order to achieve a more equitable society.

The approach I take when speaking or writing about reproductive justice is to integrate discussion of abortion bans as misogynistic in nature with the use of gender-inclusive language that clearly indicates that not everyone who can get pregnant is a woman. I don’t think we need to shy away from calling abortion a matter of women’s rights or referring to the right-wing assault on abortion access as part of a “war on women.”

When we do so, however, inclusivity demands that we also take the time to be explicit about how trans men and nonbinary folks who can get pregnant are directly harmed when access to abortion and contraception is threatened or denied, and that we advocate for healthcare practices that respect trans people’s gender identities. It isn’t difficult to do.