I went to India searching for spiritual enlightenment. I found a neoliberal heaven that catered to my worst possible self.

That’s almost true. I took my journalism class to India this past spring to cover the role of religion in the recent election. I’d done similar trips before to Israel and Ireland, but this time I wanted the students to have more than a fleeting encounter with the religion they were covering.

During a previous trip to India, the class had visited one of Delhi’s Hanuman temples, where the synesthetic overload of traditional Hindu worship (yonis and lingams, flowers, sugary prasad, gongs and incense) had left a group of cerebral journalism students with no choice but simply to be.

On this trip, I wanted students to experience something like that before they started reporting. And for myself? I wanted a break, a chance to rest after a difficult year. My younger brother’s unexpected death had emptied me out, and desperate to fill the hole, I’d taken on too much work. A weekend retreat at an Indian ashram was my go-to fantasy, my hope for healing.

I had chosen Ananda and Osho for our three-day immersion because they were located near Mumbai and Westerner-friendly. In fact, both had developed an East-West hybridity that extended from Americans in key leadership roles to a spiritual eclecticism with room for Jesus, New Age and Zen. So after flying 20-plus hours from Los Angeles to Mumbai and driving another eight hours to Pune, I’d dropped half of the students at the rural Ananda retreat and alighted at Osho with the rest.

The Osho International Meditation Resort is an urban oasis: an integrated mix of dark, sleek geometric buildings and greenery. The eating patio opens onto a huge swimming pool landscaped to resemble a small lake. The lush environs promise harmony, peace and tranquility.

Unfortunately none of that was available on arrival. Coralling and cajoling students, even grownup ones, requires energy and the last bits of mine were drained before I “lost” the group at the Mumbai airport. After the nearly day-long flight, we still had a four-hour bus ride ahead of us. When we finally found each other, boarded the bus and found boxed breakfasts of chicken salad sandwiches, I relaxed a bit. That was premature. The bus driver went in circles, clocking eight hours to travel 95 miles. Arriving at Osho, my only goal was sleep. But the registrar at the Welcome Center had other plans. First check-in, then blood tests to insure we did not have AIDS, a lengthy registration and payment.

Although Osho’s guesthouse and “multiversity” accept credit cards, the registrar requires cash for the resort’s day passes, food and other amenities. Discovering that I lacked the rupees to cover the class’ costs, a serene blonde volunteer taxied me to an off-campus cash machine. Each time the ATM refused my request, my adrenaline surged. I knew Citibank could be unreliable, but why was a peace-and-love retreat tormenting me? Returning empty-handed, I vented loudly in the crowded check-in area. Eager to calm my rising and very public ire, the registrar allowed us to check in and told me to come back in the morning.

But before we could go to our rooms, we were taken to the Galleria, Osho’s one stop shop for toiletries, souvenirs and mandated resort wear—long maroon robes for daytime activities and white ones for the evening meeting. Tetchy from hunger, lack of sleep and recalcitrant ATMs, I grabbed whatever the salesclerk handed me barely registering that my students were modeling different styles. Two hours into my stay, I was not feeling the love.

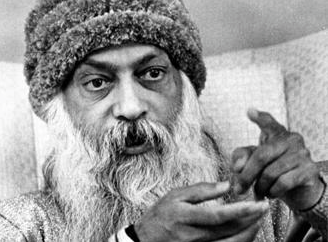

In his heyday, Osho (1931-1990) was less about love than the pursuit of happiness. Labeled the “sex guru” for what were liberal attitudes in 1960s India, Rajneesh, as Osho was known then, was equally contrarian on politics, economics, and religion. A fervent capitalist, he hailed science, denounced institutional Hinduism and encouraged followers to leaven their asceticism with sensual pleasure and material comfort. (His vision of the enlightened man was “Zorba the Buddha.”) In 1974, when he opened a center in Pune, Rajneesh’s teachings reflected his eclectic tastes. Culling inspiration from Zen, the human potential movement, Gurdjieff, and Christianity, the charismatic guru offered “dynamic meditations,” practices that included dancing, screaming, deep breathing, jumping, humming and spinning.

In his heyday, Osho (1931-1990) was less about love than the pursuit of happiness. Labeled the “sex guru” for what were liberal attitudes in 1960s India, Rajneesh, as Osho was known then, was equally contrarian on politics, economics, and religion. A fervent capitalist, he hailed science, denounced institutional Hinduism and encouraged followers to leaven their asceticism with sensual pleasure and material comfort. (His vision of the enlightened man was “Zorba the Buddha.”) In 1974, when he opened a center in Pune, Rajneesh’s teachings reflected his eclectic tastes. Culling inspiration from Zen, the human potential movement, Gurdjieff, and Christianity, the charismatic guru offered “dynamic meditations,” practices that included dancing, screaming, deep breathing, jumping, humming and spinning.

Americans and Europeans were attracted by Rajneesh’s idiosyncratic methods, but the Indian government was less enthused. Authorities thwarted the movement’s attempts to move to a larger property and denied visas to foreign acolytes. The center’s tax exempt status was rescinded, and religious leaders railed against Rajneesh’s heterodox teachings.

Faced with open hostility, the guru and his closest associates decamped from Pune to a 64,000-acre spread in Oregon. Dubbed Rancho Rajneesh, the commune was envisioned as the hub of a self contained city. When locals resisted the planned expansion, the Rajneeshiis (as disciples were called) tried subterfuge, then violence and bioterrorism to get their way. When all such efforts failed, the masses fled and the leaders faced imprisonment. With the aborted venture in disarray and looming charges of immigration fraud, Rajneesh made a plea bargain to leave the US. To this day, uncertainty shrouds the Oregon venture: What did Rajneesh know and what did his inner circle conspire secretly in his name?

Rajneesh returned to the Pune center in 1987 and later renamed himself “Osho,” an honorific title for a Buddhist priest. He enlarged the Pune property and called it Osho, too. The eponymous site, he decided, would be a multiversity and meditation resort, refocused on teaching and developing new meditative techniques. Whether a religious genius or a savvy entrepreneur, Osho anticipated the psychic rootlessness of 21st century cosmopolitan elites hungry for “something more” and happy to pay for it. The spiritual equivalent of Dylan’s Candy Bar, the retreat center’s enticing wares were culled from esoterica worldwide. Lord Buddha had a Bodhi tree, but Osho’s clientele could choose from tarot cards, horoscopes, aromatherapies, kabbalah classes, tantra and oh so much more.

Yet just as Osho, the center, was coming into its own, Osho, the man, died—too soon to savor a renewed enthusiasm for his teachings. By the 1990s, his mix-and-match style reflected Western tastes—it was spiritual but not religious (Osho called it a “religionless religion”), wildly eclectic, zealously materialistic and focused on individual well-being. Basic classes were open to all who paid a modest daily fee and key was the early morning “dynamic meditation,” an hour mash-up of heavy breathing, screaming, jumping and dancing.

The multiversity offered then, as it still does, a wide range of spiritual, mystical, New Age and therapeutic teachings and practices. During our stay, guests could experience centering, energy balancing, massage, astrology, breathing, hypnosis, counseling, neo-Reichian bodywork and workshops on laughing and crying, seeking the feminine, primal feelings and family dynamics. Classes were an hour but courses could take weeks or months. Prices were consistent with similar offerings in New York or Los Angeles.

But I was unaware of either the multiversity’s curricula or its cost when I began my own journey of self-exploration. I was intent on paying my bill, attending orientation and returning my white robe for a perkier, more flattering style. The next morning, rupees in hand, I went to the Welcome Center. I had five minutes before our orientation session so when the registrar asked me to wait, I explained that I needed to get to my students. But he demurred, joining a tanned and tangle-haired young couple sitting at a computer. The three proceeded to navigate the check-in procedure.

I counted to ten, which only increased my agitation: now I’d lost another ten seconds. Orientation would start without me. Desperate, I marched to where the registrar sat with the tousled couple and spoke crisply and clearly, “I need to pay now.” The registrar looked surprised, the couple was startled and the rest of the room went silent. Oshoites do not speak loudly. They speak softly, and address each other as “friend.” No ego and no anger. My loud assertions violated a basic code of the center: rather than transcending my base self, I was wallowing in it.

From what I could see, Osho’s clientele were well-heeled seekers from across the globe. During the weekend, there were (mostly young) men and women from France, Italy, Germany, Russian, Israel, the U.S., Japan, Argentina and India. Some, like us, were there for a short stay, but others came to study at the multiversity for a week or even several months. Still others worked at the resort, supplying volunteer labor in exchange for courses.

Seekers came to Osho to satisfy their spiritual needs. Most wanted to find their best self. My need, I realized as I yelled at the registrar, was to channel my worst. I was already angry—why did my brother die, why must I work so hard, why wasn’t my husband sorrier to see me go—and primed to snap. Now something about Osho—its spiritual preciousness, regimented excess, brazen capitalism—threw me over the edge. I couldn’t just register, I had fill out forms, take an AIDS test, and rustle up cash. I couldn’t set my own schedule. I had to buy special clothes, eat at mandated times and attend an orientation.

Rather than the dream of a peaceful retreat I’d cherished for months, this was New Age fascism.

While other guests enjoyed the dissonances – a search for self set against a late-night bar scene, costly multiversity classes, and nightly videos of Osho’s rambling, racist and misogynist lectures, I felt like screaming. So I did.

I screamed at the Welcome Center and the registrar left the couple to take care of me. I screamed at the Orientation Center, and the staffers asked what I needed, I screamed at the woman sent to calm me down, and she promised help soon. Why was I feeling so much anger? I was jetlagged, check. I felt hassled, check. My brother was still dead, check.

But there was more. I was angry because Osho wasn’t living up to my fantasy. I expected paradise but landed at Wal-mart. Spirituality was packaged, experience was monetized, and consumers were expected to be docile. Idiosyncratic imperatives –rules on how to spoon food on plates, appropriate body odors, prohibitions on coughing and sneezing—were mandated. As a “guest” at Osho, I was expected to pay up and shut up.

I’m not naïve. Religious institutions and spiritual movements need money. I’ve paid for High Holiday tickets, passed the plate at church, and dropped bills into the basket at yoga class. But Osho’s opacity and its denial of the obvious (robes and shampoos, wine and brownies, books and videos were all moneymakers) bothered me.

My fuming was worthless. Orientation still started 45 minutes late. My students and I, packed into a classroom with 20 other guests, were led through a set of meditation exercises. We danced, spun, hummed, and took deep primal breaths. We looked like kindergarteners and felt like idiots. Pushed by the trainer, a white-haired Dutch woman, to shed the “I” that judges, we put on blindfolds to ease our freedom. Jumping and shouting “Hoo, Hoo,” we became other to ourselves. When I could see again, I realized that one student was missing and several others looked stunned.

Later at lunch, I stayed away from the members of the class. I didn’t want to join their chorus of complaints (crazy exercises, crazier rules), but neither could I defend what we’d seen, heard and done. It was easier to enjoy the food, stare at rich people and then take off for the Galleria. I’d schlepped the white robe, folded in its plastic bag, all morning. Finally I could exchange it for a nicer style. The clerk, an older American woman, told me that was impossible. The transaction was in the computer, there were no exchanges, and the rules had to be followed. I countered her every argument with my one of my own. I was tired and she had forced this on me. I didn’t like it. I hated it. I hadn’t even taken it out of the packaging.

Our exchange grew so heated that her co-worker, an Indian with the fierce bearing of Yogananda, joined us. He too, recited the rules, explaining the impossibility of my request.

But I was in a frenzy. I shook with the righteous fury of an innocent trapped by a capitalist cult masquerading as a “meditation resort.” “You say you are my friends,” I cried. “But this is not how a friend behaves.” The Indian gave me a long, hard look, “You are not a good person,” he hissed. Then he gave me the robe I wanted.

I told myself I’d beat the system. Not only did I have the robe I wanted but I’d pierced an Oshoite’s calm. It felt like a victory, albeit with a spiky edge.

I spent the next few hours in classes. I signed up for a psychic healing session at the multiversity. A waif-like Spanish woman led me to an attic aerie filled with small, colored bottles. I lay down on her table, closed my eyes, and she moved her hands above my body, sighing and making soft clicking sounds. I waited for a mysterious shift in my consciousness but I felt nothing. It would take several sessions to unblock my energy, she said. Would I like to come back tomorrow?

Now, months later, I’m unsure about why what happened next. On my way back to my dorm, I felt compelled to visit the Galleria. Finding Yogananda, I apologized for screaming at him. He must have assumed that I was on the path to my true authentic self because he smiled and asked if he could hug me. When he did, something broke inside me.

My grief and anger, loneliness and regrets remained. So did my frustration with Osho’s neoliberal haven. But none of it mattered as much. My brother was dead, but so was the fever dream of spiritual escape that had landed me in Pune. I had not found enlightenment, but I was awake.