“How does it feel to be a problem?” – W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

For W.E.B. Du Bois, to evoke both feel and problem in the above quote is to see himself through the eyes of the white American and understand himself in terms of deficit. But while Du Bois doesn’t deny that structural racism exists, in the word feel he creates distance from only seeing himself as a problem, pointing instead to the possibility and vitality of the Black intellectual project as a spiritual task. Du Bois’s evocation of feeling in this context interrogates the defining white gaze, a gaze that might assert that to be American is to be white; to feel is to slip out of this moral accounting and to insist on the viability of being Black and American.

Employing Du Bois’s insight of feeling in this way might help us to think differently through a particular phenomenon in our contemporary moment—the proliferation of book discussions on race, racism, and anti-racism in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, and more specifically in Christian communities.

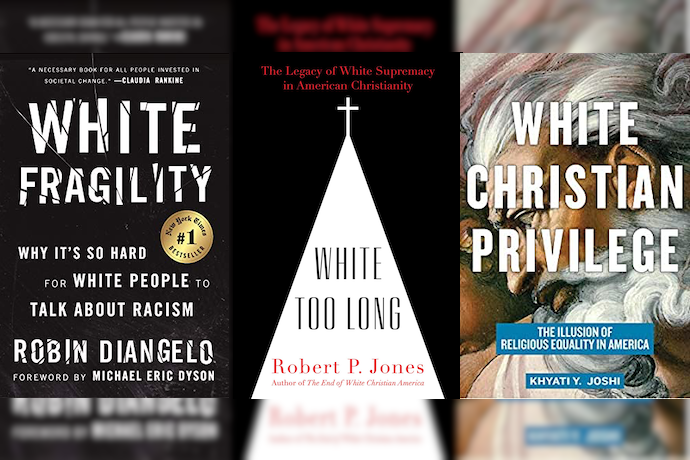

Considering how three books—Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility, Robert P. Jones’s White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity, and Khyati Y. Joshi’s White Christian Privilege—feel their way through, around, and inside the intersections of whiteness and Christian theology—suggests that the feeling and formative work in these works is as important as what they deem important to communicate.

This is to say that even when whiteness is aware of itself and attempts to undo itself, the virtual omission of non-white voices and lives remains far too prevalent. If whiteness only comes into relief by fixing blackness as a problem, this reinforces rather than undercuts the problem.

It should perhaps not be surprising that, based on anecdotal evidence at least, DiAngelo’s book would be widely taken up in majority-white Christian congregations. DiAngelo herself was hired by the United Methodist Church recently to do a series of videos on deconstructing white privilege (an initiative at the center of an unfortunate Twitter stir with Eric Metaxas’s assertion that “Jesus is white”). Here on RD, Eric Vanden Eykel correctly observes that Metaxas’s tweet is a symptom of a widespread ignorance about structural racism, particularly among white Christians.

So turning to DiAngelo might be a natural step in countering this ignorance given that the framework of white fragility raises whiteness to the surface and allows DiAngelo to mediate white confession for her readers. Perhaps it’s precisely DiAngelo’s authoritative rendering that people find attractive. Such “confessions” are necessary, but they can also easily create the illusion that one has done the work to “undo” racism. While DiAngelo’s work directly addresses anti-blackness, in large part her examples of Black people are interpreted to prove a point, and sometimes erroneously, as several have observed regarding her example of Jackie Robinson. White Fragility might resonate with majority-white congregations because of how it all too easily overlays with the relative absence of black church members in those spaces, without disruption.

Whiteness invisibilizes its operations in a number of ways. It depends on rendering racial surfaces as real, the origins of race as natural, and morality as singular. The affective clarity of whiteness—its conviction in mapping the world and organizing non-white bodies—allows for it to entangle itself with our closely held myths. So the deeper and more difficult reckoning for Christians is how Christianity in the modern era helped to create and enable whiteness, and how this shapes the realities of communal belonging, both within and without the church.

Reading DiAngelo can be an entry point, but not the only one. In this vein, Robert P. Jones’s White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity shades the story of white supremacy in explicitly theological and contemporary terms. Jones offers a personal and empirically driven account on the entanglement of racism and white Christianity on U.S. soil, what Willie James Jennings and J. Kameron Carter depict more conceptually elsewhere.

White Too Long is an instructive narrative, particularly for white Christians, mapping the intimate relationship between white supremacy and Christian belief and formation. Indeed, weaving together the strands of Jones’s account might allow us to see the defense of chattel slavery, direct participation in lynchings of black men and women, and promotion of housing segregation precisely as the outcome of theological formation, with no apparent contradiction between the two.

Jones, founder of the Public Religion Research Initiative (PRRI) and born and raised as a Southern Baptist in the deep South, relates the experiences of his feelings of God’s protection to the orientation of white, Christian bodies toward each other. While it was only later in life that Jones learned of the racist beginnings of the Southern Baptist Convention in 1845, he asserts that the feeling of divine protection nurtured in his church community was the other side of maintaining racially segregated spaces. Racially segregated spaces are existential spaces of comfort, even if protected by violent means. Narratives of racial and sexual purity, and theological orthodoxy, help to reinforce this feeling of comfort and God’s provision.

Purity in this sense draws its energy from what it’s protecting people against: the countless, smaller interpretative moves of evasion, silence, and gaps in sermons, church and cultural histories, and hymns, all of which naturalize racially segregated institutions and lived spaces as extending God’s “hedge of protection.” Collectively, then, white Christians, conservative and progressive alike, must ask themselves to what extent the existential comfort they may feel is related to the real absences of non-white persons in their communities.

Jones “confesses” himself that his theological formation in churches and educational institutions required no grappling with either the racist legacies of these institutions nor his own whiteness. His account, therefore, is revealing not only for the connections that he makes between white supremacy and Christian theology but also of how it gives telling evidence of this very theological formation. The confessionary whiteness on display depends on a narrative of blackness that sometimes relies on graphic accountings of black death and trauma.

Given how these deaths have been erased in larger narratives—particularly ones that involve white Christian complicity—and continue with wearying predictability, this narrative needs to be told. But it raises the question of whether his accounting reinscribes the white gaze, of whether white empathy can only be nurtured through the description of black pain. It risks situating black folks as the objects of salvation, rather than collaborators and creators of it, in our ecclesial spaces.

In raising the relief of white supremacy, Jones presents his account partly as a story of “American Christianity.” But American Christianity is also a story of how Black, indigenous, Latinx, and Asian Christians have been creating space for themselves in American Christianity, of making the formative connections between their racialized identities and faith in ways that attempt to fully embrace both.

To read Jones’s work through this absence (saved for the acknowledgments) is therefore to invite the reader to a different kind of feeling work. Engaging the streams of Black, indigenous, Latinx, and Asian American Christian theology is to feel a kind of decentering of the white gaze that only sees non-white bodies as a “problem.” It’s to begin to do the affective work of recalibrating our moral vision about race not only because it’s about the correction of wrongs, but also because it’s about love and decentering oneself for the sake of others’ belonging.

To this end, unfeeling whiteness is a journey that not only requires the necessary decoupling of American from “white,” but also Christianity from “American.” Reading Khyati Y. Joshi’s book, White Christian Privilege, then, feels all the more pressing today. The conspiracy theories swirling about Kamala Harris’s religious identity, for example, aren’t notable for whether or not they’re accurate, but rather for how they familiarly echo the ones circulated about President Barack Obama in denying blackness as representative of American political power.

Similar interrogations of belonging can take place closer to home. In a recent conversation with Senator Cory Booker, Joshi herself, an Indian American Hindu woman, recounted a childhood memory of first learning about Jesus from a classmate who told her that she was “going to hell.” To feel like a “problem,” then, in America as someone who isn’t Christian is to raise in relief the Christian theology that underpins the legal and cultural structures and histories of America. It’s to raise in relief the stories of Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, indigenous spiritualists, and atheists who were felt and determined in these structures as “other” but nevertheless often struggled to claim their place in the project of American political belonging. It’s to point precisely to reading the stories of non-white, non-Christians as a necessary decentering of Christianity as part of deconstructing whiteness.

Joshi’s book points to how the secular, political project of belonging isn’t about denying religious differences or disavowing our complicity with racism and religious intolerance. The work of anti-racism includes collective and individual confession of anti-blackness; it should also move to the expansive work of interreligious and cross-racial encounter and friendship. White Fragility and White Too Long can play initial parts on that journey, but also are incomplete without hearing, and therefore feeling, non-white and non-Christian reckonings of our collective histories.

This is the harder and longer work of boundary-crossing in our relationships, schools, workplaces, and government institutions; of centered black and non-white voices. Joshi calls us to re-envision the American landscape in our mind’s eye so that gurdwaras, mosques, synagogues, and temples—much like the one that her parents help build in the Atlanta, GA area, many years ago—no longer feel like a threat or problem, but a realization of hope for “a more perfect union.” It is to echo, in a different way, Du Bois’s insistence—that one can be Hindu and American, Muslim and American, Buddhist and American; and that perhaps this possibility can lead to transformation for us all.