Is it Okay to Celebrate the Death of Rush Limbaugh — or Should We Let the Dead Judge the Dead?

Rush Limbaugh was a persistent son-of-a-gun, by which I mean he persisted at being an…

Read More

Rush Limbaugh was a persistent son-of-a-gun, by which I mean he persisted at being an…

Read More

When my best friend died of cancer earlier this year, at age 44, her body was cremated, a choice now made by close to half of the people in the US.

Read MoreDeath is not final. Last week, four scientific big thinkers settled into their seats on…

Read MoreThe living and the dead are sharing territory all the time, at Terri Schiavo’s bedside and in the post-apocalyptic South of The Walking Dead.

Read More

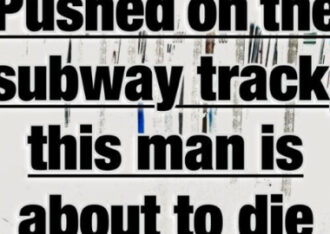

Without the framing device of community, without any context in which to shape the interpretation of the events, such images become simply sensational, the prick of pain without the moral payoff.

Read More

We rely on a journalist to just stand by—it’s a practical act of witness: while you report the story you stand in the presence, neither blinking nor stepping up.

Read More

Is it simply a part of the conflicted role of the journalist or does the photo’s work as cultural catharsis ignore the specific agony of the victim’s loved ones?

Read More

Many (obviously) look to religion for answers. Not me. Even if I consider myself somewhat religious, I have a hard time accepting the life-after-death claims of my own religion, Judaism. The dilemma is not uncommon: Although 80-90% of Americans believe in God, some 25-50% do not believe in life after death (the numbers depend on the study). So when considering death, many of us turn to less spiritual pursuits. Two recent books attempt exactly that: to explore the nature and meaning of death without religious filters. Shelly Kagan’s Death uses philosophy to define mortality and how best to live with the knowledge of it; Dick Teresi’s The Undead explores how science and technology is changing how we define death—and not for the better.

Read More

It is easy to blame the war machine or the pornography industry, but the more mundane problem is with our addiction to visual thrills. What some people see as a lack of moral vision (watching a porn video, for example) is perhaps better approached as an amoral astigmatism, a lazy eye, a privileging of the visual over our other evolved senses. The thrill of watching may mingle with compassion for those being harmed, but unless you as a viewer do something to actually alleviate that suffering, you are only a voyeuristic addict, entranced by the power of the gaze.

Read More

What might it mean for a synagogue, a church, a mosque, or a temple, to set up a video screen in its sanctuary and play these images of death from September 11—and then turn around and respond to them? What reinvented rituals might result from a ritualized, contextualized reception of these images? Such communal framing gets us beyond the questions of morbid voyeurism because it eliminates the one-way dimension and places images within a social setting. It further allows us to reflect and come to terms with dying, thereby stirring the potential for a good death.

Read More