“Ferguson has always been burning.”

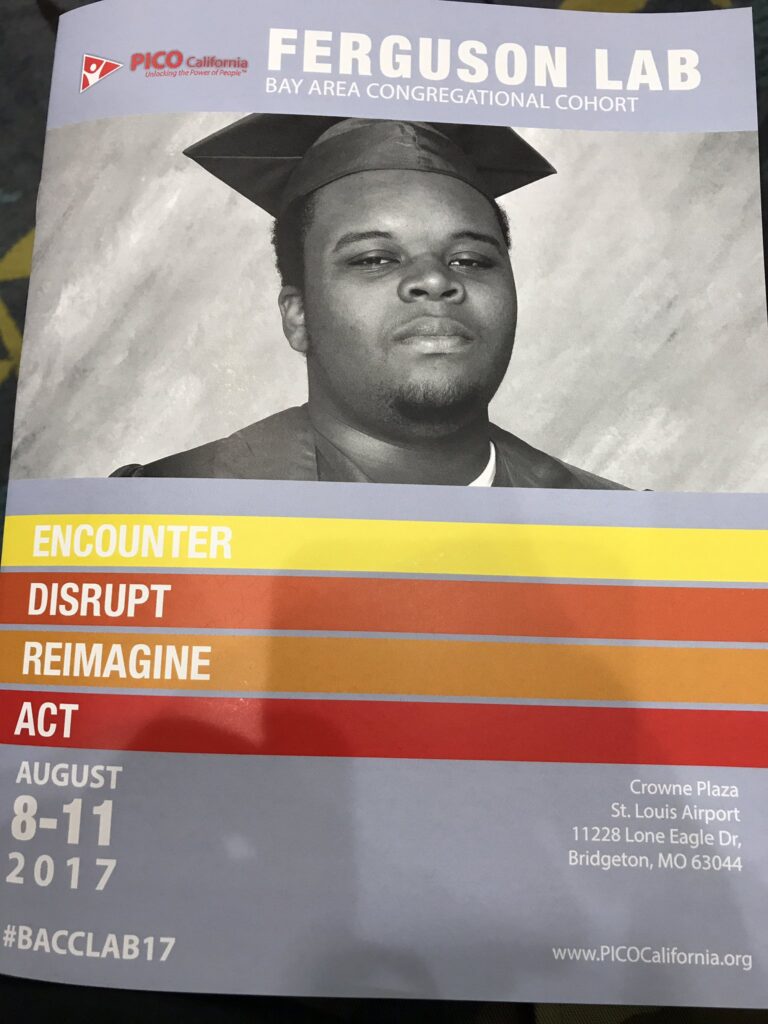

That is how the Reverend Ben McBride of PICO California began his talk on the first day of the Bay Area Congregational Cohort’s “Ferguson Lab” in August.

For the three-day event, clergy, congregants and activists from across California had gathered in Missouri to learn what it meant to be a witness to social injustice— and how to reimagine divine justice.

As I sat in a frigid hotel conference room in Bridgeton, Missouri, a suburb of St. Louis that represents the outer edge of the city’s white flight, I took stock of the 30-odd people surrounding me. An interesting mix, some of the attendees were longtime activists of color, some seemed to be defectors from the traditional black church, some were white Christian millennials eager to dive into social movements and a few were older white congregants starting to recognize the meaning of privilege for the first time. Regardless of where individuals were in their faith or their activism, all were rapt with attention, ready to listen to the lived experiences of Ferguson and Missouri residents.

“We need to see Ferguson as a burning bush,” McBride continued, “as the unquenched fire of those suffering under a repressive regime. The bush had always been burning, but God was waiting for someone to see it, for someone to look at something outside of themselves.”

A San Francisco native who started out as a youth pastor to at-risk children, McBride now devotes much of his time to combating gun violence and police brutality in Oakland. Ferguson is a sort of mecca for the minister, the birthplace of a new way of resistance and the “most transformative” experience of his life.

Before 2014, McBride was not an activist, he explained. He was a spectator to the rising din of police brutality activism, and had “never protested a day in his life” until he came to Ferguson, he said.

Now he has been to Ferguson for protest actions eight times, has been arrested by Missouri police, and leads regular trips to the area in the hopes that others will have the same epiphany he had. He eschews respectability politics in favor of direct protest, hoping to afflict the comfortable and rattle the complicit. He has also increasingly embraced social media as a tool for changing perspectives, using the #JusticeForJesus hashtag to tweet modern retellings of the arrest and crucifixion of Jesus through the lens of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Ferguson has taken a fraught place in the American imagination. The small neighborhood and its problems weren’t on the national radar until 2014 when it became a flashpoint for police violence and the Black Lives Matter movement.

But, as McBride explains, the neighborhood has become what he calls a “trauma tourism” site, with civil rights activists passing through to get their “Ferguson badge” and moving on. He says: “we don’t want to be here just because of what happened. We want to be here for the people.”

Protests, police, and a patch of sidewalk

And so, on August 9, the third anniversary of Michael Brown’s murder, I joined Ferguson Lab attendees on a bus to Ferguson with two local activists—Rika Tyler and hip hop artist T-Dubb-O—to walk the same path that the eighteen-year-old Brown took on that fateful day in the summer of 2014.

Both in their 20s and born in St. Louis, Tyler and T-Dubb-O became engaged politically after the death of Mike Brown, putting themselves on the front line of the uprising. They soon started Hands Up United, a grassroots organization that fights for the liberation of black and brown residents through civil disobedience and education. The network has expanded since its inception, with Tyler and T-Dubb-O becoming connected to Palestinian, Mexican, and Brazilian activist groups.

Tyler and T-Dubb-O took us through the blighted suburbs of St. Louis that are slowly being eaten away by urban decay and overrun with dilapidated buildings and empty lots. When we reached the small community of Ferguson, I was taken by how normal and everyday it seemed. There were well-tended houses and apartments, closely cropped lawns, people walking their dogs and retired residents hanging out on stoops and patios. As Tyler emphasized, this is a working-class black community.

The one element that marked it as a place where something terrible had taken place was the significant police presence.

As we visited Ferguson Market and Liquor, the corner store Michael Brown visited before heading to his encounter with Wilson on Canfield Drive, there were at least six Ferguson police officers with accompanying cruisers guarding the entrance to the liquor store that had become a hotspot for protests in the wake of Brown’s murder.

“The story of Ferguson didn’t start on Canfield Drive. The story of Ferguson is a whole lot longer.”

Tyler recognized each of them and knew them by name. She had become well-acquainted with them during the first 100 days of protests after August 9th. Many of them were the same officers who beat, gassed and arrested her along with other protesters.

Her decision to become an activist and start the social justice organization Hands Up United was further complicated by the fact her father is a Missouri police officer.

“A defining moment for me was during a protest action we organized, I spotted him on the other side with the police officers,” she said. “That’s when I realized what I did meant nothing to him.”

Even though he occasionally donates to her organization, Rika says her relationship with her father remains strained and they speak infrequently.

The final stop on our walk was Canfield Drive, the street where officer Darren Wilson pulled over his police SUV and approached Brown. Within less than 90 seconds of this interaction, Brown would be dead. Wilson would later describe adolescent Brown as a “demon” with superhuman strength.

A memorial plaque is now placed on the patch of sidewalk where Wilson first began to fire upon Brown from inside his Chevy Tahoe. A few yards further down, in the center of the street, is a makeshift memorial atop the spot where Michael’s body lay on the street for four hours before he was moved. I knelt down and placed my hand on the cement. Though the temperature was only in the 80s when our cohort visited, it was hot to the touch.

A mix of roses, stuffed animals and cards adorned the block of darker asphalt that didn’t match the rest of the pavement. This is because the original 160 square-feet patch, permanently stained by Brown’s blood, was removed and repaved roughly two years ago at the request of his family. They didn’t want people casually driving over the site of their son’s crucifixion.

Sacred ground

Earlier in the day, our group had stopped at the Cahokia Mounds. The most complex archaeological site north of Mexico, the Mounds were once part of a native civilization larger than London. Little remains of the city, and the sacred landmark with its intricate earthwork is now a popular course for joggers.

“The story of Ferguson didn’t start on Canfield Drive. The story of Ferguson is a whole lot longer,” said Rev. McBride after a moment of silence. “It started here 1000 years ago when these people were just living their way of life, not knowing they were about to be ‘disappeared.’ Remember you aren’t standing on your own ground, this is red ground.”

As we climbed the 154 steps to the summit of the central mound, Dr. Vince Bantu, a professor at St. Louis’ Covenant Theological Seminary, related the ground we were standing on to the ground we would later be standing on in Ferguson.

“If you’re a person of color in Missouri, it’s just part of the normal experience. You go five miles over the speed limit, you sit in jail for two weeks.”

“The entire history of St. Louis is of certain people being oppressed so that other groups could advance. In order to benefit one community, they would disenfranchise another.”

Even St. Louis’ most nationally recognized symbol, the Gateway Arch, towering over the St. Louis skyline from where our group stood on the mounds, was a “symbol of American terrorism” to the black communities that its construction displaced. Through eminent domain, 37 blocks of homes and businesses in the thriving black St. Louis community were razed to make room for a monument to the United States’ western expansion. To add insult to injury, discriminatory hiring policies made many of the promised construction jobs unavailable to non-white residents. Upon its completion in 1965, it would be dedicated “to the American people.”

More than five decades after its erection, the city the 630-foot arch overlooks hasn’t seen much change in how it treats its residents of color.

Missouri is the Mississippi of today's black liberation movement. Blk people have no rights in this state. It's a proven fact at this point

— Tef Poe the 🐐 (@TefPoe) September 15, 2017

According to the Mapping Police Violence project, the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department has the highest rate of police killings per population in the nation based on data from 2013 to 2017. Of the 28 people killed in police encounters in that four year period, 23 were black. And shortly before our trip, the NAACP issued its first ever travel advisory for black people headed to Missouri over heightened police tensions and discrimination.

Last month, when former police officer Jason Stockley was acquitted on charges of murdering black motorist Anthony Lamar Smith in 2011, St. Louis residents flooded the streets outside City Hall. They were soon confronted with police, and 80 of them were arrested. Some officers could be heard chanting, “whose streets, our streets” as they detained protesters, co-opting a popular mantra for Black Lives Matter demonstrators.

The display was further proof of the ongoing over-policing of St. Louis and its surrounding communities, including Ferguson, and of just how indifferent local institutions remain to the plight of its marginalized citizens.

Bassem Masri, a St. Louis native who was on the front lines during the Ferguson protests and live-streamed much of the actions, says he now takes the bus because he got tired of the random stops and numerous traffic tickets he would get each month due to racial profiling. At 30 years old, he says he has been stopped or arrested for unjust cause more than 150 times.

“If you’re a person of color in Missouri, it’s just part of the normal experience. You go five miles over the speed limit, you sit in jail for two weeks.”

Masri, whose family is Palestinian and who spent some time living in Jerusalem, compared Ferguson to living in the West Bank.

“It’s like we’re under military occupation. In the black neighborhoods, you see police SUVs every couple of blocks. In white neighborhoods, you don’t see the police unless you call them.”

“Flint is everywhere.”

Another threat facing the black communities of the Gateway City is one that is as of yet underreported in the media: environmental racism. This is a type of violence that isn’t as visible as police brutality but is just as insidious.

Flint, Michigan received a lot of media attention in early 2016 when it was brought to light that more than 100,000 residents were exposed to toxic levels of lead in the city’s drinking water. This type of environmental neglect isn’t just happening in Flint. For decades, chemical companies have been using poor areas in Missouri as dumping grounds for radioactive and nuclear waste.

Missouri State Sen. Maria Chappelle-Nadal, an environmental activist, has long been a voice in the wilderness regarding this issue and says she often explores the St. Louis area with a Geiger counter.

“Flint is everywhere. There are cancer clusters appearing in and around St. Louis, and there aren’t any reliable studies being conducted on the problem.”

Radioactive waste is a problem in Missouri. Someone has to stand up and advocate! #70yearsTooLonghttps://t.co/DVB7rsCsnF

— MariaChappelleNadal (@MariaChappelleN) September 13, 2017

For years, residents of the majority minority suburbs circling St. Louis have complained of health ailments commonly associated with exposure to toxic waste. A neighborhood group made up of local mothers called Just Moms STL has been campaigning for federal and state intervention to deal with the radioactive waste that has been dumped in St. Louis suburbs dating all the way back to the Manhattan Project. Republic Services, the Fortune 500 company that owns several of the landfills connected to radioactive contamination, insists that adjacent neighborhoods are safe.

Rika Tyler of Hands Up United, who said she wouldn’t even give her dog unfiltered city water, feels it’s yet another form of violence inflicted upon the city’s black and brown residents.

“When I think of the murder of Mike Brown, I also think of the high rates of black people around Ferguson who are getting cancer, who are born with deformities, who are getting asthma, who are experiencing all these health problems. They’re being murdered too.”

“I see you.”

During the trip I was repeatedly greeted with the phrase Sawubona—the salutation of choice for the many of activists on the ground there. It’s a Zulu word that means more than just hello.

Rev. McBride explains, “It means I see you, and because I see you, you exist.” The response Ngikhona, simply means, “I am here.”

“Seeing the blatant expression of institutional and structural racism forced me to pause and actually reevaluate my own sense of the American story and what the role of faith is in that,” says McBride. “Things have not changed here. People are still being targeted, they’re still being stopped, they’re still being murdered.”

Like the biblical bush that burned unacknowledged until someone decided to see it, Ferguson three years post-uprising is still striving to be seen.