Largely lost in the coverage of the Rev. William Aitcheson, the priest serving in a Northern Virginia Catholic Church until he was revealed as a former member of the KKK, is his history of abortion clinic protests. According to the Washington Post:

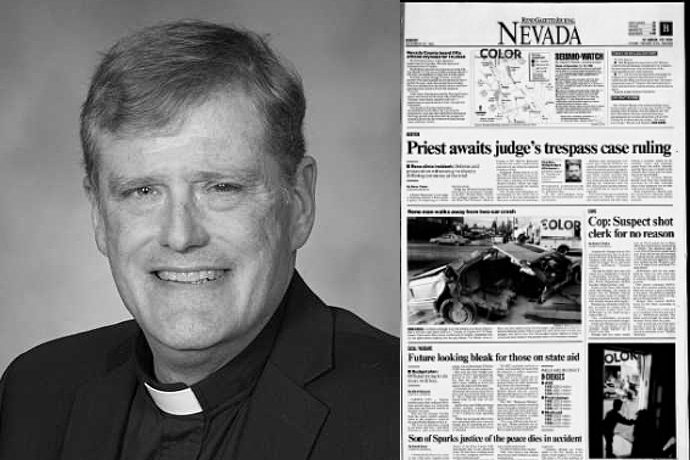

In 1992, Aitcheson was arrested on charges of trespassing on the property of the West End Women’s Medical Group clinic in Reno. … Damon Stutes, the doctor who still runs the clinic, recalled the priest as a regular protestor, who “yelled at” people coming in and “acted like a caged lion that was just holding himself back.”

That a priest was involved in confrontational anti-abortion activism shouldn’t come as a surprise. The period of the early 1990s marked a confluence of direct-action tactics aimed at abortion clinics and anti-abortion activism by Catholic priests, who had been exposed to the escalating anti-abortion rhetoric of the Catholic hierarchy.

The same year that Aitcheson was arrested in Reno, New York Archbishop John O’Connor led a high-profile march on an abortion clinic in New York City. Previously he had expressed support for Operation Rescue, which would go on to lead a series of confrontational abortion clinic blockades in Kansas in the summer of 1991.

It’s also instructive that about the time that Aitcheson was burning crosses in southern Maryland and plotting to bomb the NAACP, a Catholic anti-war and anti-abortion activist named John Cavanaugh-O’Keefe was pioneering abortion clinic protests not far away in Northern Virginia, where he led a series of clinic sit-ins in an attempt to bring the nonviolent tactics preached by Martin Luther King and Gandhi to the movement to end abortion.

But the tactic that O’Keefe started turned violent when one of his disciples, Michael Bray, led the bombing of several Washington, DC-area abortion clinics, which energized a generation of radical anti-abortion activists who attacked clinics and terrorized providers. Thus, noted David Garrow, began “the anti-abortion movement’s precipitous slide from principled nonviolence to deadly terrorism.”

Over the next decade, this radical right of the anti-abortion movement would come to look more and more like the KKK says Garrow, as many in its leadership espoused violent tactics to stop abortion and attacks on clinics became commonplace. In 1993, as the anti-abortion rhetoric escalated, two abortion providers, Dr. David Gunn and Dr. John Britton, were murdered.

The murders of Gunn and Britton, as well as that of two Boston-area clinic workers the following year, should have been a moment of reckoning for the leadership of the Catholic Church, which increasingly had made opposition to abortion its foremost cause. Abortion clinic protests had become violent and contentious. But while some condemned the maelstrom, others equivocated. O’Connor, the head of the U.S. bishops’ powerful Pro-Life Committee, rejected a call for a moratorium on clinic protests by Boston’s Cardinal Bernard Law, saying he would agree to such a moratorium “on condition that a moratorium be called on abortion.”

Thus it would seem that Aitcheson may have traded the socially unacceptable radicalism of white supremacy for the church-sanctioned, subtler terrorism of anti-abortion activism—the pickets and “sidewalk counseling” and epithets shouted at patients and providers, all with the same shades of hierarchy and patriarchy and traditionalism, of privilege lost and barely surpassed rage.

After his arrest in Reno, Aitcheson was transferred to the Archdiocese of Arlington in Northern Virginia. It was a fortuitous move. Arlington has long been one of the nation’s most conservative dioceses and is especially outspoken in its abortion opposition.

The website of St. Leo the Great, where Aitcheson served, provides a page of anti-abortion resources on its website, including a link to the controversial and largely discredited organization Priests for Life. Last year, Father Frank Pavone, the founder of the group, placed “unborn child’s corpse on the altar in Priests for Life’s chapel as part of two Facebook live videos urging people to vote for Donald Trump on Election Day.”

The parish is deeply embedded in the anti-abortion movement. The current head of the largely Catholic March for Life is a member of the parish. Last year St. Leo the Great provided training to area high school and college students who protested at an abortion clinic in nearby Falls Church, presumably advising them on how to not run afoul of the federal FACE Act, which was put into place to limit harassing and violent actions against abortion clinic staff and patients.

It’s unclear at this point whether Aitcheson will return to St. Leo’s. What was initially hailed as a brave reckoning with the past and the events in Charlottesville was quickly revealed to be desperate attempt to head-off a denouement by a former parishioner who stumbled across Aitcheson’s past on Google. As I’ve noted, the church has yet to fully come to terms with the racism in its own ranks, never mind the radical roots of the anti-abortion activism it has long fostered.