I first heard Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II speak at a Moral Mondays rally in Raleigh that I attended with my classmates back in February 2014.

It was powerful and incisive in its moral criticism of North Carolina policies bound to hurt the most vulnerable and…strange. As an Afro-Latino millennial from New York, I’m bound to find—let’s be honest—a coalition led by a charismatic male Christian pastor to be a bit old-school.

It was powerful and incisive in its moral criticism of North Carolina policies bound to hurt the most vulnerable and…strange. As an Afro-Latino millennial from New York, I’m bound to find—let’s be honest—a coalition led by a charismatic male Christian pastor to be a bit old-school.

Nevertheless, I can’t deny the importance of Rev. Barber’s coalitional work and consistent commitment to justice. I fear overly fragmented political or moral responses won’t dismantle a well-financed status quo. Coalitions are needed, but not the ahistorical kinds that promote erasure of particular struggles. Rev. Barber’s activism is grounded in a rich historical memory, as demonstrated in his new book The Third Reconstruction and the accompanying interview here on RD. His calls for “fusion friendships” are not based on simple idealisms and platitudes of unity and reconciliation but on overlooked precedents.

Equally as important, he is quick to condemn terrorism and violence on all fronts, including U.S. violence in the Middle East and white terrorist attacks within this country. While I may not exactly share Rev. Barber’s sometimes Southern-centric outlook, I’m aware that I can’t understand the United States apart from the South or apart from the Reconstruction(s). As someone whose roots are newer to the U.S. and whose roots go deeper south to the Caribbean part of Colombia, I’m aware that Rev. Barber raises problems and alternative possibilities that go to the roots of this country, roots that the North is entangled in no matter how much the Northern consciousness scapegoats the South.

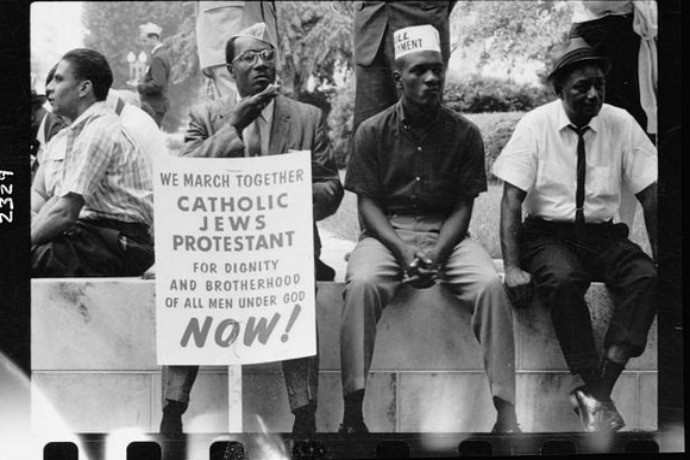

Rev. Barber considers the moments when “blacks and whites, Jews and Catholics, labor and youth came together” in the 1950s/60s as an example of fusion politics and a Second Reconstruction. Perhaps another contemporary example of what Rev. Barber calls fusion politics is embodied by Wheaton College professor Larycia Hawkins. Her interfaith solidarity, and her concerns for labor and justice, represent the politics that threaten hegemonic Christian stances that feign neutrality—but underwrite the forces exacerbating hate and poverty.

One thing I deeply appreciate about Rev. Barber’s fusion politics is that it calls Christians to another ecclesiology in which Christians and Christian churches are not turned in on themselves. Living the Gospel should mean good news for all of our neighbors.