In this RD10Q, historian Zev Eleff uncovers the little-known story of how American Jews became a clergy-led community.

RD: What inspired you to write Who Rules the Synagogue?: Religious Authority and the Formation of American Judaism?

Zev Eleff: In 1991, historian Jon Butler called for scholars of American religion to consider how “church authority” worked to shape “lay faith.” A few biographers had heeded Butler’s call, but I felt that there was much work to be done. I was convinced that religious authority and its overall impact had been overlooked as a valuable feature of religious life.

For Jews, changes in religious authority helped determine changes in prayer and ritual, synagogue construction and gender dynamics. Here was an opportunity to offer scholars of religion a monograph that focuses on the formative century of Judaism in the United States, one that places this faith community in the broader context of American religion.

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

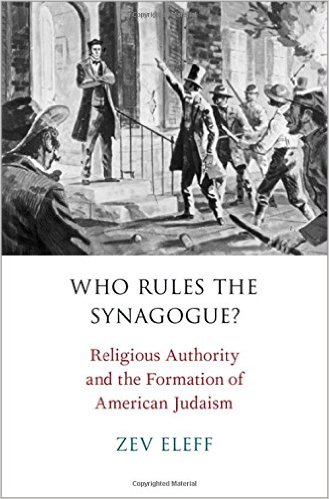

Who Rules the Synagogue?: Religious Authority and the Formation of American Judaism

Zev Eleff

Oxford University Press

June 2016

Is there anything you had to leave out?

Absolutely not. Mine is a very tight work that seeks to explore certain questions and answers them, hopefully satisfactorily. Still, this monograph has offered me new questions and paradigms to help understand other historical epochs. My study concludes in the 1880s, just before a mass migration from Eastern Europe grew the American Jewish community from 250,000 women and men to about a million at the turn of the 20th century. The changing nature and culture of the Jewish community in the United States provides new variables to explore. However, the role of religious authority in determining new developments is more than evident in other periods.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

This was a dilemma for me. My particular focus is American Jewish history. I’ve written about it in books and articles. I study it, read it, live it. I also consider myself a student of American religion (Protestantism, Catholicism and Islam) and modern Jewish history (in the United States and Europe). I wrote this book in a way that speaks to all of these fields and made ample use of the primary and secondary sources in all three disciplines. I also did my best to write in an engaging manner that would appeal to practitioners (rabbis, ministers, laypeople), as I think the arguments posed in my monograph have something to offer contemporary folks as well.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Entertain them? Anger them?

I certainly never try to anger anyone! This is an interesting question. I suppose, as a teacher and scholar, my role is always to engage students and readers. Entertaining, then, is a core component in any successful scholarly enterprise. My book—I think anyway—doesn’t have an agenda. As a historian, I am moved to discover (or rediscover) new ideas and facts and reconstruct a historical moment with theses and other scholarly scaffoldings. That’s my truest agenda. If I, as a historian, and the reader, as a student of history, come out better informed and more intrigued by the complexities of religious life—then I’ve succeeded.

What alternative title would you give the book?

Oh, dear. The first title was Pulpits, Power and Pews. My editors at Oxford University Press, Theo Calderara and Marcela Maxfield, were very wise and gracious to do away with that overdone display of alliteration. Then we considered When the Rabbis Reigned. Finally, thanks to a suggestion by my mentor, Dr. Jonathan Sarna, we agreed upon Who Rules the Synagogue, an allusion to the political scientist Robert Dahl and his very influential work on political power, Who Governs.

How do you feel about the cover?

The cover is elegant and up to the high standards of Oxford University Press. Several years ago, I found the drawing of Rabbi David Einhorn rebuking his congregants in Baltimore (he was a fierce abolitionist and they were not) in the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives. At the time, I thought it might make for a good cover. I am very grateful that my publishers found a way to incorporate this image so prominently into the cover’s design.

What’s your next book?

I am working on a history of patrilineal descent. In the 1980s, Reform Judaism (under the leadership of Rabbi Alexander Schindler) changed the way this community viewed religious status and identity. Before then, all Jewish communities—save for the Reconstructionists—identified Jewishness through one’s mother and not the father. I will focus on the substantial political and religious literature during this decade that stresses the “fracturing” and “polarization” of American life. The patrilineal decision decentered American Judaism, causing rifts within the various movements and shifting the center of concern from the United States to Israel. So far, I have delivered a number of talks on this subject and received great feedback.