In the 1930s, the socially conservative cultural critic and poet, T.S. Eliot, bemoaned his contemporary society “in which blasphemy is impossible.” I wonder where that society went, or if it ever really existed.

The latest blasphemous event came to a head in the last few weeks as the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery caved under well-placed protests to remove David Wojnarowicz’s artwork, A Fire in My Belly from the NPG’s exhibition, “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture.” The story has been well-trod in all the major press outlets, while blog blitzes from the right and street-level protests from the left have all but obscured any actual artwork that might exist at the heart of the matter.

In the midst of the hoopla is a deeply religious artwork made by an artist struggling with and through the embodied life of the spirit.

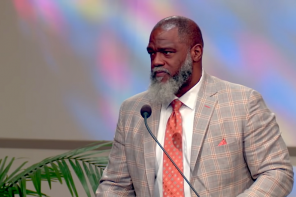

David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992)

At the age of 37, David Wojnarowicz died from AIDS-related complications. He had spent much of his life in and around New York City, with significant travels throughout Latin America and Europe. Catholic schooling left him scarred, but it is simplistic to suggest he turned against religion. Instead, he sought a more primal, even childlike faith, in touch with the natural world and the bodies of other people. His work in photography, film, and video continually expressed this, even when it became the most confrontational. He was openly gay, and outspoken about the AIDS crisis especially after his friend and lover, Peter Hujar, died from the disease in 1987.

He entered the “Culture Wars” in 1989 when the National Endowment for the Arts rescinded funding for a catalog and an exhibition on the topic of AIDS. Wojnarowicz had contributed an essay that attacked several public figures for supporting policies he believed helped the spread of AIDS. The controversy at this time, along with other right-wing criticisms (Senator Jesse Helms led the way) against the artists Andres Serrano, Karen Finley, and Robert Mapplethorpe, brought Wojnarowicz into national media attention beyond the art world.

The following year, Wojnarowicz went on the offensive, and filed a $5 million suit against Donald Wildmon, Methodist Minister and founder of the American Family Association, after the AFA mailed tens of thousands of pamphlets that spoke against the homoerotic themes of Wojnarowicz’s work and included many details from the artist’s photo collages. The suit also included charges of copyright infringement for reproducing imagery without permission. The AFA was ordered to cease all distribution and to publish and distribute a correction. Wojnarowicz was awarded a token $1 for damages. Many saw this as a victory for Wojnarowicz, as no one had taken on such a legal battle before.

Fire in My Belly

Several versions of the video have emerged and been distributed across the Internet, making it even more difficult to find a single artwork at the heart of the matter. Wojnarowicz appears to have once put together a 30-minute version, then made a 13-minute version in 1986-87. A 7-minute version appeared posthumously, but Wojnarowicz himself scrapped the project and the work remained unfinished in his life (the end of the 13-minute version clearly says “in progress”). Footage from these films was edited down to a 4-minute version for the “Hide/Seek” exhibition by co-curator Jonathan Katz, along with Bart Everly, and mixed with audio from an ACT UP march. Another 4-minute version appeared with a soundtrack Diamanda Galás (“This is the Law of the Plague” with lyrics from Leviticus 15). The 13-minute version that Wojnarowicz edited is silent.

Much of the imagery comes from Wojnarowicz’s time in Mexico in the 1980s, and shot on Super-8 film. Mexican Day of the Dead ceremonies mix with Aztec statues; scenes of professional wrestling merge with cockfights and bullfights; strong crucifixion imagery merges with street scenes from Mexican cities and towns; a man masturbates, mummified bodies appear to come alive, butchers carry cow carcasses, and through it all a sombrero-wearing marionette dances, attempting some comic relief until the puppet is finally shot and burned. It contains many disturbing images. There’s no question about that.

Perhaps most striking are the surrealist images and connections. A loaf of bread, having been cut in half, is sewn back together with a large needle and thread. With the juxtapositions of a crucifix and blood, the broken bread conjures up “the body of Christ, broken for you.” Except here that brokenness is attempting to be mended.

One other surrealist borrowing is the ants, and it is the “ant-covered Jesus” that became the rallying cry for the right. Eleven seconds of this was enough to get the artwork/exhibition/Smithsonian Institution labeled “anti-Christian.” In Fire in My Belly, ants roam across a Day of the Dead altar scene, and a mass-produced crucifix. The surrealist painter Salvador Dalí used images of ants throughout his works, perhaps best seen in his 1931 Persistence of Memory, and the infamous 1929 film Un Chien Andalou, (made with Luis Buñuel). When Dalí was a child he found a wounded bat, which he kept, only to return later to find the bat being devoured by ants. Ants are scavengers, feeding off the dead and decaying.

It doesn’t take much to realize the main theme of A Fire in my Belly is death. More specifically, it is the vulnerability, penetrability, and perpetually possible disintegration of the human body. This fleshly mortality became especially real to Wojnarowicz in the still-emerging AIDS crisis of the time. Thus, by necessity it is a deeply human and deeply religious artwork. Religious rituals and myths have long accompanied death, that great unconquerable force. And in the film we see Day of the Dead images, Aztec sacrifices, and mummified bodies juxtaposed with the death of Jesus. This is a meditative piece in the memento mori (“remember you will die”) tradition, and similar to that of many religious traditions for many ages. Which does not mean these images are pleasant and easy to look at. No warm and fuzzy pop spirituality this.

Christianity itself has produced some of the most gruesome images of tortured, dying, suffering, and dead bodies, especially Jesus’ own body. From Latin American Roman Catholic piety to German Protestantism, the dead and dying Jesus is a point of power, passion, and ultimately compassion. Take, for example, Matthias Grünewald’s Small Crucifixion (early 16th century) in the publicly funded National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. Grünewald’s great altarpiece in Colmar, France, is much better known, but the Small Crucifixion gives that same putrid body, those same mangled limbs, pocked skin oozing pus and blood.

That Christ on the cross is actually dead, and the body so dead that ants might eat it, is both the most orthodox Christian statement, and the most scandalous. But here is where the power of words and images begin to show their differences.

In Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot, the character Ippolit kills himself. In his suicide note he meditates on a reproduction of a 16th century painting by Hans Holbein, The Dead Christ:

The picture seems to give expression to the idea of a dark, insolent, and senselessly eternal power, to which everything is subordinated, and this idea is suggested to you unconsciously. The people surrounding the dead man, none of whom is shown in the picture, must have been overwhelmed by a feeling of terrible anguish and dismay on that evening which had shattered all their hopes and almost all their beliefs at one fell blow. They must have parted in a state of the most dreadful terror, though each of them carried away within him a mighty thought which could never be wrested from him. And if, on the eve of the crucifixion, the Master could have seen what He would look like when taken from the cross, would he have mounted the cross and died as he did?

Holbein’s is an image, as Prince Myshkin says in Dostoyevsky’s story, that could make one lose one’s faith. (Dostoyevsky himself saw the original in Basel earlier in his life and it had a deep impact on him.) And yet, the image offers a profound meditation on the power of death, that “dark insolent, and senselessly eternal power.” The picture becomes, like so many before and after, a point of great healing, compassion, and understanding about this central, paradoxical thing that Christians hold dear: Incarnation.

Now, in the time of Advent, a time of reflection on the in-flesh-ment of the divine in a human baby, there is little more important than a deep understanding of the humanity of Jesus. And to be human means to take on this mortal body, to suffer, and to die. To become food for the ants.