The decision comes on page 8. The sound of screaming is coming from behind a locked door in a warehouse. You have to do something. What do you do? If you try to break the door down, you turn to page 20.

If you run to get the warehouse manager, you turn to page 33.

Escape from the Haunted Warehouse

Anson Montgomery (Author) and Keith Newton (Illustrator)

Chooseco, 2015

Like the classic books loved by children of the 1980s and ’90s, the story starts with a disclaimer: “BEWARE and WARNING,” it says. “You and YOU ALONE are in charge of what happens in this story.”

And like those classics, the story is built on a key idea of the American mode of spirituality known as “spiritual but not religious.”

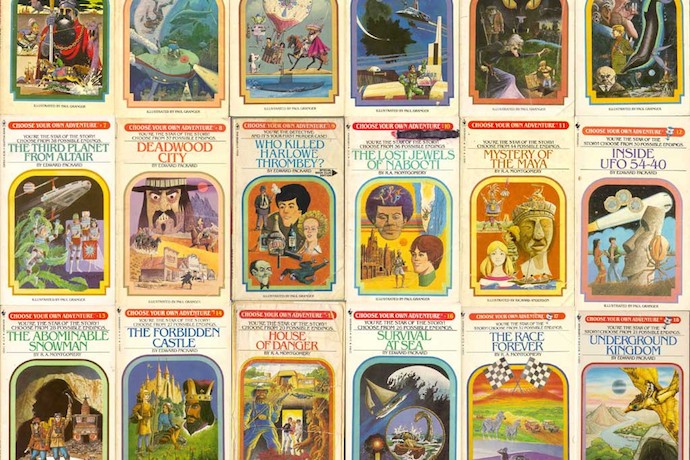

The Choose Your Own Adventure series that Edward Packard and R.A. Montgomery created in the late 1970s is sometimes connected to wishy-washy modern practices of believing. The series title itself was even used as a put-down by Andrew Sullivan in a post on those who mix-and-match or take-and-leave and treat religious ideas as playthings.

But there was a very serious religious idea behind those popular children’s books.

Montgomery, who published the CYOA books after Packard’s idea was rejected repeatedly by more mainstream presses, believed the innovative, role-playing format of the stories taught a moral lesson. They were designed from a humanist, spiritual-but-not-religious perspective. They engaged readers with Montgomery’s core belief, illustrating again and again a central value of human agency and responsibility.

“It’s finally saying to you, you’re involved,” Montgomery said in one of the few interviews he did on the subject. “What are you doing and why are you making these choices?”

Montgomery, who died late last year at his home in Vermont, was largely known for his role in turning the CYOA books into a franchise that eventually extended to more than 230 titles selling 250 million copies in 40 languages. He personally wrote more than 30 of the original books, as well more than a dozen other titles in spin-off series. (He even got his family involved in the writing process, including his son Anson Montgomery, who wrote Escape from the Haunted Warehouse.)

The news of R.A. Montgomery’s death at 78 was met with a number of tributes and appreciations on the Internet. These books were huge in the lives of many American children and have even been seen as presaging the cultural shift to the Internet age, where audiences are no longer happy to passively consume content, but want interaction. The history of the books is intertwined with the history of the Internet.

There’s also a somewhat secret, spiritual-but-not-religious history of the CYOA books.

The belief system at their core can be traced to Montgomery’s brief stint at Yale Divinity School in 1958-1959. According to his wife Shannon Gilligan, Montgomery only lasted a short time at the school because he was more interested in his own adventures than academics. He was “kicked out,” Gilligan writes, after “spending too much time skiing and mountain climbing.” In his short time there, though, he became acquainted with the school’s chaplain, William Sloane Coffin, who had a huge impact on Montgomery. In the last years of his life, writing on his personal blog, Montgomery would frequently quote Coffin, calling him “my old friend Bill.”

Coffin, a liberal Protestant in the Social Gospel tradition, believed that being a minister of the gospel required him to be an activist and an advocate of social justice. He preached often on courage, as his Times obit noted, calling it the virtue that “makes all other virtues possible.”

This emphasis on social justice involved a reorientation of religion, according to Coffin. Humans ought not to wait on God to solve human problems, but ought to take responsibility for solving the evil and suffering of the world. In an interview with PBS near the end of his life, Coffin made this argument explicitly:

Every time people say, when they see the innocent suffering, every time they lift their eyes to heaven and say, ‘God, how could you let this happen?’ it’s well to remember that exactly at that moment God is asking exactly the same question of us: ‘How could you let this happen?’ So you have to take responsibility.

It was a theme Montgomery would make his own, though rather than work through the church, as Coffin had done, he became a classic example of one who was spiritual but not religious.

Historian Leigh Eric Schmidt has described these “restless souls” as “wayfarers who attempted to join their spiritual individuality to social practice.” He writes that they have sought to empower individuals to take charge of their own spirituality, in projects aiming to remake the world and the self.

The popular characterization of the spiritual-but-not-religious person is of someone a bit flighty and unserious. The spirituality is a pastiche of confused and conflicting ideas. The seeker is typically thought of as embracing a mishmash of conflicting ideas—Catholicism and reincarnation, Buddhism and crystals, kitschy angels and dreamcatchers—which, if taken seriously as ideas, would not seem to fit together.

For Montgomery, however, joining spiritual individuality to social practice meant a special emphasis on individual decisions, individual choices. He didn’t necessarily advocate that people believe a bit of everything, but rather that they take responsibility for what they did believe. Where organized religion often insists that believers must take on beliefs in sets, Montgomery would point out that each choice was a choice, even if it were an unreflective one. He thought people should be more careful, more serious, more specific about their choices.

As he described the mission of the Choose Your Own Adventure books, they brought readers face to face with their own choices. “Implicit in the choice is an ethical or moral approach or decision,” Montgomery said. “But that’s never spelled out and it’s never told. Whatever you decide is what you decide.”

After he left Yale Divinity School, Montgomery went to work in the field of experimental education. He worked for the Wall Street Journal, developing ways the newspaper could be used in classrooms, before starting Waitsfield Summer School in Waitsfield, Vermont in 1966. There, he sought to find ways to teach students who had struggled in school. Montgomery used games as a teaching tool, an approach that attracted the attention of a Cambridge, Mass. think tank, Clark Abt Associates. Abt was inspired by his work on Air Force war games in the early days of the Cold War, and who thought role-playing simulations could be a powerful educational tool, published Serious Games the year after Montgomery went to work for the think tank in 1969.

Montgomery started designing role-playing games in the early 1970s. One put players in the situation of having to work together to solve an energy-shortage crisis. Another put Peace Corp volunteers in culturally sensitive situations, and allowed them to play their way through potentially problematic encounters with non-Western cultures. The role-playing exercise was used by the Peace Corps (which, incidentally, was started by William Sloane Coffin).

As Montgomery would explain on his blog many years later, at Abt Associates he learned the power of a simulation model, “an approximation of reality without the risks of the real world.”

“You make choices leading to different endings,” he explained. “If you don’t like the ending, you can start again with difference choices leading to a different ending.”

Even the biggest problems could be solved by helping individuals be more conscious of the choices they made, Montgomery believed. There are reasons that others on the left would come to be critical of this faith in individual choices. With a globalizing economy and mounting concerns about environmental crises, it often seems that the neoliberal structure, which places all moral responsibility on the shoulders of individual consumers, is itself to blame for some of the intractable, systemic problems. Emphasizing individuals’ choices can be a way of insulating structural issues from critique. Montgomery’s focus never wavered, though. As he moved from divinity school to working with learning-challenged children, to an education think tank, to role-playing game development, he always focused on the idea of individual agency and responsibility.

This core belief made him exactly the right person to hear about Packard’s idea for a new kind of kids’ book.

Packard, a lawyer from New York City, spent the end of the 1970s trying to get publishers to show some interest in his book. By his account, he had grown lazy while making up a rambling, multi-part bedtime story for his children. When he began to ask them what they wanted the character, a shipwrecked boy named Pete, to do, it occurred to him this would be an interesting idea for a book.

Packard was more interested in the puzzle of producing the book than in the spiritual vision that inspired Montgomery. He liked the challenge of charting out the possibilities within the physical constraints of a book. Publishers were turned off by the technical difficulties and experimental nature of the project, but Montgomery, who had launched his own small press in Vermont to specialize in children’s books, recognized the potential.

Together he and Packard developed Sugar Cane Island, which Montgomery branded “The Adventures of You.”

The protagonist was now in the second person, “you,” and the books opened with a warning that captured the core of Montgomery’s spiritual-but-not-religious humanism: “BEWARE and WARNING! You and YOU ALONE are in charge of what happens in this story!”

The first book sold 8,000 copies, an impressive number for an independent press.

The series was then bought up by Bantam Books and re-branded Choose Your Own Adventure in 1980. An initial marketing push gave 100,000 copies of The Cave of Time to librarians, who loved the concept and the effect it had of getting kids to actually sit down and read. Selling for $2.95 apiece, more than 50 titles were published over the next three years, and about 30 million copies were printed.

Connoisseurs have noted the differences between Packard and Montgomery. Sean Michael Robinson, who was obsessed with the books as a child, recalled that Packard’s titles were more internally consistent. “Although we often were drawn to the concepts and themes of R.A. Montgomery’s books, we were put off by the lack of narrative logic,” writes Robinson.

Sean Munger, on the other hand, another avid childhood reader, preferred Montgomery’s books for the same reason Robinson didn’t like them.

“Montgomery had no qualms about blasting off into any old direction he felt like, the more outlandish, the better,” he wrote. “As a result, half-baked ideas involving aliens, smugglers, monsters or secret societies often popped up in his work.”

Munger points to House of Danger, published in 1982, as a classic example of Montgomery’s style:

You don’t a chance to go inside the House of Danger until later, with most of the early choices centering around the wild stuff that comes out of the house and tries to attack you. Such as huge, snarling, man-eating, sentient holographic chimpanzees.

Yes. You read that right. Huge, snarling, man-eating, sentient holographic chimpanzees.

Your encounters with these creatures, and with various other ne’er-do-wells, spins the book off into so many directions it’s hard to keep track of them. Depending on which choices you make, the House of Danger houses a counterfeiting ring, a secret organization for international peace, a paranormal hotbed of ghosts left over from the 1887 prison riot, or a spearhead of an alien invasion. Whatever happens, there’s never a dull moment.

The disregard for established boundaries also happens to be a key part of the rejection of organized and institutional religion. As Schmidt writes, “journeying across the bounds of traditions, denominations, and institutions has emerged as a familiar, if still creative, course of explorations for many Americans.” Montgomery sought to be creative in exactly this sort of spiritual exercise.

Montgomery’s CYOA plots also seems to place him more firmly in the spiritual-but-not-religious rather than secular humanist camp. The point, for Montgomery, was that whatever might exist or not exist, dealing with it would be a matter of human choices.

Or, as the second Humanist Manifesto put it in 1973: “We reject those features of traditional religious morality that deny humans a full appreciation of their own potentialities and responsibilities . . . While there is much that we do not know, humans are responsible for what we are or will become. No deity will save us; we must save ourselves.”

The unexpected challenges of the House of Danger, whether 19th century ghosts or aliens or holographic chimpanzees, must be dealt with by individuals. By “you.”

For Montgomery, the same was true of real-life challenges like global warming. As he reflected in a blog post during a long Vermont Winter a few years before he died:

We as individuals and as societies make choices all the time. The history of our species is amazing: fire, numbers, alphabets or pictographic language, medicine, architecture, money and banking, art, music, laws etc. Choices got us there. We are still making choices both as individuals and societies. Not all of them are good—but, we can change the bad choices, we hope.

The children’s series that Montgomery helped to create put readers in exactly that position, again and again. The title of the series is sometimes taken, now, to indicate a kind of religious frivolousness, though for Montgomery it was anything but that. Choose Your Own Adventures were a kind of spiritual project that he hoped “would make some profound changes in the way people make decisions in their lives.”

The latest entry into the series, written by Montgomery’s son, is said to the be the scariest. But, like the others, it’s also meant to be reassuring.

“Don’t be afraid,” Montgomery said in 2010, when asked to sum up the Choose Your Own Adventure message. “Understand that we are all confronted with choices everyday of our life. And it’s new, it’s exciting, and sometimes it’s really, really hard.”