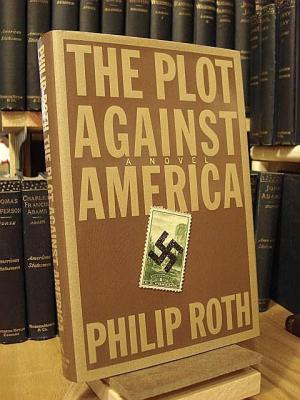

Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale triumphed at the Emmys last night, capping a culture-grabbing comeback for Margaret Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel. But if we’re still casting about for literary maps of what might happen and what we should do in the Trump Era, another candidate is certainly Philip Roth’s 2004 novel The Plot Against America—an alternate history about the coming of fascism to America.

It’s a book that may (or may not) have been written as a warning about a different coming of Christian fascism, that of the George W. Bush presidency-at-war. Indeed, Roth was supposedly so worried that his novel would be read as a kind of parable for the Bush administration that he wrote an open letter before the novel was published, urging readers not to view it in such terms.

But the warning itself might have been just another ruse. Roth was famous for crafting literary personae who at once spoke for and didn’t speak for the author. In Philip Roth’s Operation Shylock, for example, the narrator—called “Philip Roth”—becomes aware of a self-authorized con-man called “Philip Roth” who preaches the simple message that in order to stop anti-Semitism, the Jews of Israel should simply leave and relocate to Europe.

When we read Roth pronouncements, we take them with a grain of salt. We’ve been warned.

The Plot Against America is an alternate history set in 1940, during which American aviator, anti-Semite, and fascist sympathizer Charles Lindbergh defeats President Roosevelt in the November election. History as we know it alters course: the isolationist administration signs agreements with Nazi Germany and Japan recognizing their areas of influence and conquest and pledging to stay out the war. Pearl Harbor doesn’t take place, and the allies fight on without U.S. support.

The Plot Against America is an alternate history set in 1940, during which American aviator, anti-Semite, and fascist sympathizer Charles Lindbergh defeats President Roosevelt in the November election. History as we know it alters course: the isolationist administration signs agreements with Nazi Germany and Japan recognizing their areas of influence and conquest and pledging to stay out the war. Pearl Harbor doesn’t take place, and the allies fight on without U.S. support.

Meanwhile, a newly vocal, nationwide anti-Semitism is given a boost, and the child narrator of the novel—named Philip Roth —describes the new social order as it takes its toll on his family and his Jewish neighborhood in Newark. The Lindbergh administration adopts a kind of liberal fascism, with programs to make Jews into “better Americans” by relocating families out of their neighborhoods and into rural communities “where parents and children can enrich their Americanness over the generations.”

Life becomes increasingly unbearable for America’s Jews, culminating in anti-Jewish pogroms and riots across the U.S. But Lindbergh disappears one day, and the plot twist in The Plot Against America is that the famously kidnapped Lindbergh baby has been secretly raised in Nazi Germany, a hostage by which Germany forces President Lindbergh to do its bidding. With Lindbergh gone, an emergency election is held: Roosevelt is elected in 1942, the Axis powers declare war on the U.S., and history seems to snap back into the story of world events we know. Normalcy is restored.

Donald Trump’s Russian Plot Against America?

As a literary map for the coming months or years the novel gives us a lot to go on: the increasing nativism of isolationist America, the newly outspoken and muscular anti-Semitism (amidst a wider hostility to other racial and religious minorities), violent demonstrations by fascists and white supremacists, the collusion with a foreign power in attaining the presidency – coerced, it turns out, with Lindbergh, but willing, it increasingly appears, with the Trump campaign’s Russia ties. A foreign adversary with hostile intent intervenes in a U.S. presidential election to help elect a sympathetic president and prevent the election of a candidate it deems an obstacle to its foreign policy.

Germany’s power to blackmail Lindbergh by holding his child hostage gives retroactive justification to his political decisions; we might wonder about the purported Russian kompromat file assembled on Trump, of financial or sexual details, that might be similarly being used to encourage sympathetic policies.

What we might like best about the novel is its narrative of historical elasticity: one might curve the normal course of history out of its natural path, but when we let it go it snaps back to how it had been going to go all along. History, and history’s agents, seem to bend in the novelistic thought-experiment’s wind but not break. When Roosevelt is reelected and the country goes to war just a couple of years late, the world as we know it resumes course. The novel places great faith in the natural path of History—democracy’s great twentieth century battle with fascism—as well as the inherent resiliency of the institutions and actors that determine its course.

Reading The Plot Against America in 2017 makes us yearn for a similar natural reversion of history wherein the bad dream of foreign intervention, probable collusion, and the growth of Christian authoritarianism passes, with a president of questionable legitimacy deposed and replaced.

But this desire is ultimately where the novel reveals itself to be more foil than map for our current conditions.

The journey back to normalcy in The Plot Against America is strangely abrupt and undetailed. Where things go truly downhill in Roth’s novel is when Lindbergh disappears, trying to fly across the Atlantic to reunite with his near-teenage son. It’s Vice President Burton Wheeler who steps in to accelerate the drive toward fascism and the breakdown of the democratic order. As if to signal the acceleration, Roth moves into history mode, and just narrates the novel’s political resolution without reference to the narrator’s family, as though it were “Drawn from the Archives of Newark’s Newsreel Theater.”

Acting President Wheeler imposes martial law as riots are attributed to a Jewish conspiracy and the influence of the British, who want the U.S. in the war. The quisling Rabbi Bengelsdorf, who had helped justify Lindbergh’s liberal fascist policies, is arrested with other Jewish politicians and leaders. First Lady Anne Morrow Lindbergh is taken into custody, as are vocal opponents Roosevelt and liberal Republican New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia.

With martial law declared, riots rampant, political opponents locked up, newspaper and radio stations shut down, and the nation’s attention focused on war hysteria and conspiracies of foreign influence, the triumph of American fascist authoritarianism looks almost unstoppable.

And then the plot against America unravels with bewildering speed. The First Lady broadcasts from a secret location and then returns to the White House where, “marshaling the power of her mystique as sorrowing mother of the martyred infant and resolute widow of the vanished god, [she] engineers the speedy dismantling by Congress and the courts of the unconstitutional Wheeler administration.” This dismantling, which must include impeachment, is not described in the novel. It improbably takes just two and a half weeks, at which point the 1942 elections take place, including a special election for president that elects FDR as History snaps back into place.

It’s an unbelievable, and unbelievably fast, resolution to an alternate history that had been strangely compelling.

The Constitution Depends on Agents, not Just Institutions

On the one hand, The Plot Against America teaches us about the resiliency of American institutions – a resiliency we may desperately want to believe in. And yet in the novel’s failure to describe the mechanics of how those institutions operate – how the constitutional crises of impeachment, removal from office of an Acting President, and the arranging of a special presidential election, can all occur in just two weeks – it inadvertently teaches us a more important and troubling lesson: that our democratic institutions depend on personalities, on actual human beings who occupy their offices, to faithfully carry out their duties to the nation.

In the novel, both Republicans like Mrs. Lindbergh and La Guardia and Democrats like Roosevelt are representatives of a larger coming together of Republicans and Democrats to unseat the isolationist, authoritarian Democrat Burton Wheeler and hold new elections. Members of both parties activate the democratic institutions that restore History to its normal course. But what if there is no capital-H History? What if democracy is not automatically natural to the U.S.? What if, in particular, the president’s party cynically places the importance of its own power above democratic values and civic norms of governance?

Republican politicians, who control both the House and the Senate, have done much to slow walk or obstruct investigations into the Russian attempts to influence the election, and the increasingly probable collusion of Trump campaign officials with those efforts. We seem to wait in vain for Republicans to trigger the kind of institutional response of investigation and oversight – if not impeachment – that their Congressional offices were constitutionally designed to do.

But with the exception of several conservative intellectuals and commentators, almost no Republican politicians are willing to do more than publically criticize the Trump Administration. The pull of getting their legislative and judicial way – judges, especially on the Supreme Court in order to restrict abortion, killing the Affordable Care Act, cutting taxes on the rich – makes them tolerant of just about everything.

Their goal of dismantling as much of the welfare state as possible overrides their duties of oversight and good governance. To be sure, part of what’s at stake here is that the parties themselves have become more ideologically consistent – there just aren’t many conservative Democrats or liberal Republicans anymore in a large political middle ground. But the erosion of democratic and civic norms has been largely driven by one side’s ideological zeal. We are in an era of hyper-partisanship, but as bipartisan scholars Thomas Mann and Norm Ornstein have argued, it is an “asymmetric polarization” characterized by an ideologically extreme, uncompromising Republican Party.

Under these circumstances, something really extraordinary is going to have to happen to lead a Republican Congress to begin to vigorously investigate and rein in the President.

After all, Republican politicians and voters generally believe that Party is fighting enemies within – liberalism, the mainstream media and the “Democrat” party. In this sense, the antidemocratic, authoritarian tendencies of the Trump administration are broadly representative of those of today’s Republican Party, which has pursued policies of gerrymandering, voter suppression under the guise of combatting essentially non-existent voter fraud, and the purging of voter rolls. Indeed, significant minorities of Republican voters believe voting rights, freedom of the press, and the right to criticize government have “gone too far.”

In this sense, the Trump presidency is a symptom of white evangelical Christian authoritarianism, not the cause.

It’s not that who Trump is isn’t recognized among some Republican politicians. Opponent Marco Rubio correctly called Trump a “con artist” during the primary. Ted Cruz accurately labelled him as a “pathological liar” and a “narcissist.” It’s just that the exercise of power is the highest moral value in today’s GOP. Both Rubio and Cruz, as well as almost every other Republican politician, fell into line once Trump won the nomination. Because Republicans control the House and Senate, any hope for a snap-back of American normalcy and institutional resiliency seems remote. President Nixon still had the support of 50% of Republican voters when he was threatened with impeachment and decided to resign, a recent lawfare blog article noted, but President Trump’s Republican support remains at almost 80%. Fresh discoveries of Russian-Trump campaign ties or other infelicities occur almost daily, but many GOP voters ensconced in the conservative information-entertainment complex will hear about them not at all, or as carefully minimized versions.

If Roth’s Plot Against America is not a good literary map for our political present, that is partly because it glides over the important question of how individuals animated by political ideologies and movements have to activate the constitutional institutions and powers set out by the framers in order for them to work.

But it is also because, while Donald Trump’s presidency was enabled by a kind of perfect storm – of Hilary Clinton’s historic unpopularity, of Russia’s interference, of Trump’s appeal to rising white racial resentment, of the fragmentation of the news media and consequent rise of fake news – it is held in place by political and religious energies Roth never really understood.

81% of white evangelicals voted for Trump, a higher percentage than Mitt Romney, John McCain, or even the born-again George W. Bush received. And as we know from reading The Handmaid’s Tale and Tim LaHaye’s Left Behind series, the dominant white evangelical plan for Jews is not to make them “better Americans” à la The Plot Against America, but to convert them into born-again Christians. As I’ve written elsewhere, Roth’s irreligious upbringing was poor preparation for the religious energy that would overtake the nation during his career. The rise of American fascism in Roth’s novel is attributable to foreign intervention, but the Christian authoritarianism that continues to enable the Trump presidency is thoroughly indigenous.

It may all work out in the end, a reluctant Republican Party slowly moved by future revelations to perform the constitutional duties of the offices their members hold – after health care for the undeserving poor and taxes on the deserving rich have been sufficiently cut. But if that event comes to pass, The Plot Against America provokes a final, lingering question: might the vice president be worse than the president he replaces?